This coverage is made possible through Votebeat, a nonpartisan reporting project covering local election integrity and voting access. The article is available for reprint under the terms of Votebeat’s republishing policy.

With a handful of exceptions, all of Georgia’s 159 counties completed a monumental hand tally of the state’s 5 million presidential ballots with little variation from the original numbers.

Many counties say credit is due to county election workers. The count was actually part of the state’s scheduled audit, to be completed before the state certifies its election results Friday.

“Every county just organized quickly and got this done really fast. This is the largest hand count in modern American history, by a lot,” said Ben Adida, executive director of Voting Works, a nonpartisan nonprofit that assisted the secretary of state’s office and county election boards in implementing the audit.

Adida said he was impressed with what the counties did.

“It’s easy to forget that we don’t count ballots by hand at scale in the U.S. It’s only working because the county officials have worked so hard, gotten themselves up to speed,” Adida said.

Gwinnett County had one of the largest audit operations in the state, in part because it is the only county required to offer both English and Spanish language options on each ballot. Staff performed their count in a warehouse at the county elections department, located in a shopping center. Election workers hung out in the parking lot and grabbed snacks at a nearby supermarket on breaks between long shifts.

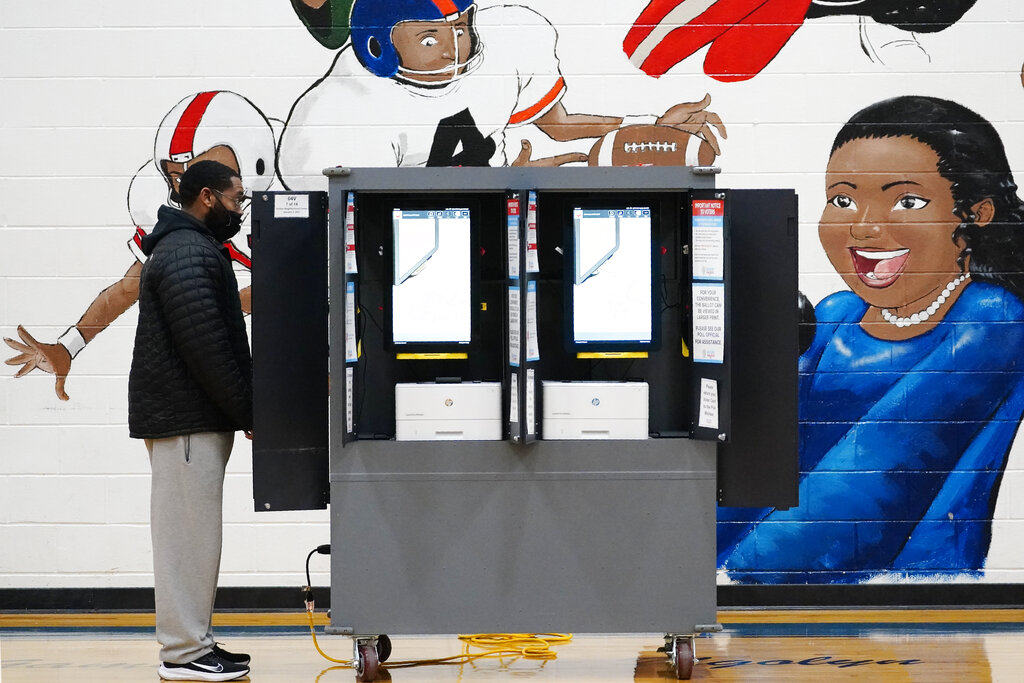

Now required by Georgia law, this is the first time an audit has been used in a presidential election. They were piloted in some Georgia counties during the June primaries, but it required extensive training of permanent and volunteer election workers in every county.

Like every other county, Gwinnett had an area set up with election workers two to a table. The workers separated the ballots into piles for each candidate, and then counted each pile. The count was overseen by poll monitors from each party, press, voting advocacy groups and members of the public.

While there was a lot of work to do, Gwinnett County officials say at one point they had too many workers on hand.

“We had a situation this morning where we had a lot of poll workers showing up that we really weren’t prepared to use,” said Gwinnett County communications director Joe Sorenson. “So they started a little late today while they tried to figure out how to best use the people they had, and let a bunch of people go.”

Any ballots with potential issues were sent to one of a few review panels that include one Democrat, one Republican and an impartial third party working in a separate, cordoned area. After being counted, the vote tallies are uploaded to the vote-counting software in a third area of the warehouse.

As the counting wound down Monday, Gwinnett Elections Director Kristi Royston had to repeatedly remind monitors to maintain social distance and that they were limited to one monitor per party per 10 tables of counting.

“We have had a wonderful three days of everyone getting along, everyone being peaceful, rules have been respected. I’m not seeing that as much right now,” said Royston over a speaker system. “I know that we’re all getting a little tired, and the process is getting to the end so everyone’s getting a little antsy about that.”

The operation was much smaller, but with a near identical setup, in Henry County.

By early Tuesday afternoon, they were down to their final pair counting votes at a table. Finished employees talked off to the side and had to be hushed by a supervisor when their excitement became too loud.

“What I’m thankful for is that I have some very dedicated workers that I could call last minute and say I need you to step in and get trained on this audit, and they were very willing and stepped in place quickly,” said Henry County Election Director Ameika Pitts.

“Henry County residents have really stepped up. Even before the training in November, I had more than 3,000 on a waiting list,” said Brook Schreiner, poll coordinator and a 10-year veteran of the Henry County elections department.

Both the audit and a possible recount are paid for by the counties. Pitts said that without the outside grants they have received, it would have been difficult to pay all the workers for the extra hours. Pitts said she has been able to ignore the pressure of national attention by focusing on doing her job.

“My objective is that I try to be as transparent as possible. My priority is making sure that everything is conducted as it should be and that we’re following policy,” she said.

The state’s audit is normally only meant to count a sample of votes cast in a race. But to reduce the risk in a presidential race decided by fewer than 15,000 votes, more than a million ballots would have had to be sampled and carefully placed back into place. So the state chose to simplify things for the counties and had them count every ballot.

The audit is different from a formal recount, which either campaign can request within two business days of state certification of the results, scheduled to happen Friday. Counties would have to foot the bill for that, too.