Evolving Civil Rights In The ‘City Too Busy to Hate’

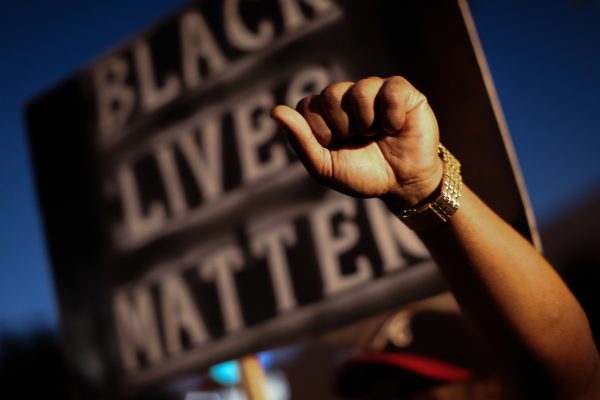

Protesters hold up their hands while chanting “hands up don’t shoot” outside Ebenezer Baptist Church in March 2014. The protesters gathered while then-Attorney General Eric Holder spoke inside the church as part of speaking tour in the wake of clashes between protesters and police in Ferguson, Mo.

David Goldman / Associated Press

Metro Atlanta has a lot to offer today’s social justice activists: economic inequality, police violence, the Mount Rushmore of the Confederacy.

But how can these things still be in a place known for its central role in American civil rights history?

“I actually don’t think Atlanta is a civil rights battleground city,” said Georgia State University historian Maurice Hobson. He studies black social movements in the south.

What he means is that, compared to cities like Little Rock, Arkansas; Birmingham, Alabama; or Selma, Alabama, Atlanta is not where the most blood was shed or where crucial legislative changes took place. Atlanta’s historic role, Hobson said, is more about its historically black colleges and universities, black merchant class and the unique ability that offered black voters to participate in the political process.

Those factors shaped the history of activism here, Hobson said.

“The idea of what we call the classical phase of civil rights, or the modern phase is extremely male dominated and it is extremely elite, black elite or middle classed,” he said.

Hobson said that earlier wave of highly educated black activists often overlooked vulnerable communities including the rural poor, women and LGBT folks. He said with newer social justice movements, like Black Lives Matter, the pendulum is swinging in the other direction.

Toni-Michelle Williams is a community organizer with Solutions Not Punishment Coalition, an offshoot of the Racial Justice Action Center formed by formerly incarcerated women, black transgender people and current and former sex workers.

“Here at SNAPco, and at a lot of social justice orgs in Atlanta, [we’re] really focused on decriminalization of black and brown folks, sex work, possession of marijuana,” Williams said.

The group was a major force behind a new city ordinance reducing penalties for marijuana possession. Williams said those arrests disproportionately impact poor people of color. The coalition has also pushed improved police policies on interacting with transgender people and the pre-arrest diversion program in Atlanta.

“I think there’s such a drive to figure out how our liberation is connected to one another’s liberation,” said lawyer Xochitl Bervera with the Racial Justice Action Center.

She said she tries to pay close attention “to the splits that can happen intergenerationally — folks who’ve been in this fight for 40, 50 years, and the young people who are just beginning — between black folks and Latino folks and immigrants and those who are born in this country, trans folks and cis folks, queer folks and straight folks.”

This summer, the NAACP launched what it called “a national listening tour” to enhance its strategic planning.

“Before hashtags and social media, the NAACP was the closest organization to Black Lives Matter that we can possibly see,” said GSU’s Professor Hobson, pointing to its consistent protests of individual lynchings.

“I do think that the old guard is trying to find its way,” said Hobson. “A lot of times the old guard is having a hard time letting go, but the young people also have to open their ears and respect the elders and just listen.”

Within the last year and a half in Atlanta, civil rights activist and former mayor Andrew Young has called protesters demonstrating against police violence “unloveable little brats,” and has questioned the substance of public criticism of confederate symbols.

Hobson points to Young’s involvement in attracting the 1996 Olympic games to city, hoping it would show “Atlanta as transcending the sordid racial history of the American south.”

He argues the Olympics were also a catalyst in reversing “white flight” out of the city in the 1940s and 50s, at the expense of some of the Atlanta’s poorer, often black residents. Hobson is one of many who see that process continuing today with the rapid pace of development and stadium construction downtown.

“In a number of ways, we really see that Atlanta has grown into a city that cares more about the business interest than it does about the people who’ve been born and raised here and here for generations,” said RJAC’s Bervera.

Hobson said complicated relationships between generations of activists are nothing new. It’s a phenomenon that stretches as far back as reconstruction. But he does see something different about this moment.

“Historically, marginalized people have been often protected by the federal government,” referring to measures like the voting rights act and school integration. Hobson believes that’s changing under President Donald Trump.

And said that means we’re likely to see an increased focus on local and state politics, which will take plenty of collaboration between activist groups and the perennial challenge for activists: engagement.

“It’s hard to get people to show up to city council at 3 p.m., when folks are working and it’s important that we have people power,” said SNAPco’s Williams.

In the meantime they’re trying to mobilize the public outrage of some over national issues into showing up for issues here.

Atlanta voters are preparing to elect a new mayor and replace nearly half the City Council. In this moment of transition, WABE is exploring “The Future of Atlanta.”