Ga. Braces For $100M Budget Hole Amid Possible Welfare Changes

WABE News

Think of the last time you picked up a jar of peanut butter.

Maybe you used it to make a sandwich or put some on an apple slice, but chances are you didn’t think much of it.

To Danah Craft, though, a jar of peanut butter is a vital source of protein for a family relying on food banks.

“This is the kind of food that helps families put a balanced meal on the table,” says Craft, the Georgia Food Bank Association’s executive director. The group helps distribute tens of millions of pounds of donated food each year to the state’s eight food banks.

Walking through the cavernous warehouse grounds of the Atlanta Community Food Bank, Craft stops at boxes of canned tuna, collard greens, sliced carrots and peanut butter.

“The food bank has a list of the most needed items, but that’s not always what comes in at any given time,” she says.

These items weren’t donated. Rather, they were bought by the food bank. It’s able to do that thanks to the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program, or TANF.

Each year, Georgia gets about $330 million in federal funds for the program. The Georgia Division of Family and Children Services, or DFCS, makes recommendations to the state budget office on how that money should be spent among state agencies and nonprofits. Last year, Georgia’s food banks got $6.75 million, and it used the money to buy 9.2 million pounds of high-demand food.

But Georgia may soon have to cut these handouts to nonprofits.

TANF expires at the end of the month. As federal lawmakers look to renew it, they’re also eyeing changes to the program that could leave Georgia with a nearly $100 million budget hole.

State officials say the effects could be catastrophic in a state where nearly 1 in 5 people lives in poverty, according to the U.S. Census.

“If you see federal funds going away that support needy families in a state that has the kind of poverty that we have, I think you can’t undersell the negative impact that it will have on our state and especially on the poorest of the poor,” says Georgia’s Division of Family and Children Services Director Bobby Cagle.

Georgia’s TANF Spending

Here’s why Georgia could lose that money.

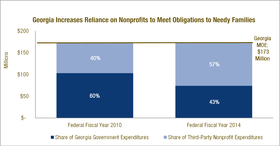

To get the $330 million in federal TANF dollars, the state must spend an additional $173 million on services for the poor. That state funding is known as Maintenance of Effort, or MOE. It’s meant to show Georgia is also investing its own dollars in fighting poverty.

But last year, only $74 million came out of the state budget. That’s down from 2009, when the state spent around $97 million.

Still, Cagle says Georgia has “never fallen below the maintenance of effort required.”

How did the state make up that missing $99 million?

To meet the MOE obligation, the state doesn’t have to spend its own money. It can give nonprofits some TANF dollars, and in return it can count some of their spending as state spending.

Georgia heavily relies on this legal funding option. The $99 million from third party dollars the state used last year to meet its funding obligation accounts for about 57 percent of its total MOE.

Now, Congress and President Barack Obama are separately considering measures to effectively end the practice of counting third party dollars. A congressional draft bill proposes to turn TANF into more of a workforce development program, while the president’s budget proposal would just end the third-party spending option.

“A significant amount of dollars have essentially been used by the states during the ups and downs of the budget and the economy to supplant what the states were or should have been doing,” said Congressman Lloyd Doggett (D-Texas) at a recent House Ways and Means Committee meeting about TANF.

“We Had No Other Choice”

Ending this practice would hit Georgia especially hard.

Back in 2011, a congressional study showed Georgia and Utah were by far the top users of third party dollars to meet their spending requirements, using this funding to make up almost half of their obligation. The practice has only intensified since.

If the state could no longer count outside spending, it would have to come up with $99 million of its own money. If it doesn’t, it loses money from the federal $330 block grant on a dollar-for-dollar basis – money that’s now being used primarily for vital state services like adoption and child welfare.

Melissa Johnson, a policy analyst with the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute, says Georgia dug itself in this hole by cutting state spending and filling the holes with federal TANF dollars.

“We’re the fifth poorest state in the nation,” she says, “and TANF is designed as a program to move people from public assistance to economic self-sufficiency, so we need, if anything, more investment in the program.”

DFCS Director Cagle defends the state’s current funding scheme. He says it was necessary during the recession to keep getting the full federal grant while still funding important state services.

“We did it because we had no other choice,” he says. “We simply did not have state funds.”

Georgia Without Third-Party Dollars

Cagle says while these proposed changes to TANF are still pending, if they do happen, DFCS would likely cut its handouts to nonprofits.

“This is not somewhere the state wants to go, but I think if we have to come up with large amounts of money in a short order, we have to look at every alternative, and unfortunately some of those are not good,” he says.

That uncertainty has nonprofits worried.

Craft, of the Georgia Food Bank Association, says food banks have come to depend on that money as their rolls grew during the recession.

“The philanthropic sector has stepped up in a significant way over the last five years, and I think the biggest concern is how much more can charity do?” she says. “Asking the charitable sector to step up yet again is really straining the resources of a lot of programs.”

Johnson of the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute says the governor and state legislature should use this opportunity to put up the matching funds for TANF.

“The nonprofits really don’t have to suffer if Georgia just prioritizes continuing to fund those programs,” she says.

But Cagle of DFCS says it’s not conclusive that the state will do that. He says the governor’s decision to add $35 million to the DFCS budget last year will help start moving the division away from its reliance on third-party spending, but it won’t be enough.

In the meantime, all eyes are on Washington this month as TANF’s fate is decided.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))