Georgia child welfare agency wants fewer sent to foster care

Georgia lawmakers say they plan to rewrite a bill that would slow the flow of children into foster care, after juvenile court judges and children’s advocates raised concerns that the measure helps the state’s child welfare agency at the expense of children.

As drafted, the measure pushes juvenile court judges to transfer fewer children into state custody, and gives the state more time to prepare to receive children who are ordered into foster care.

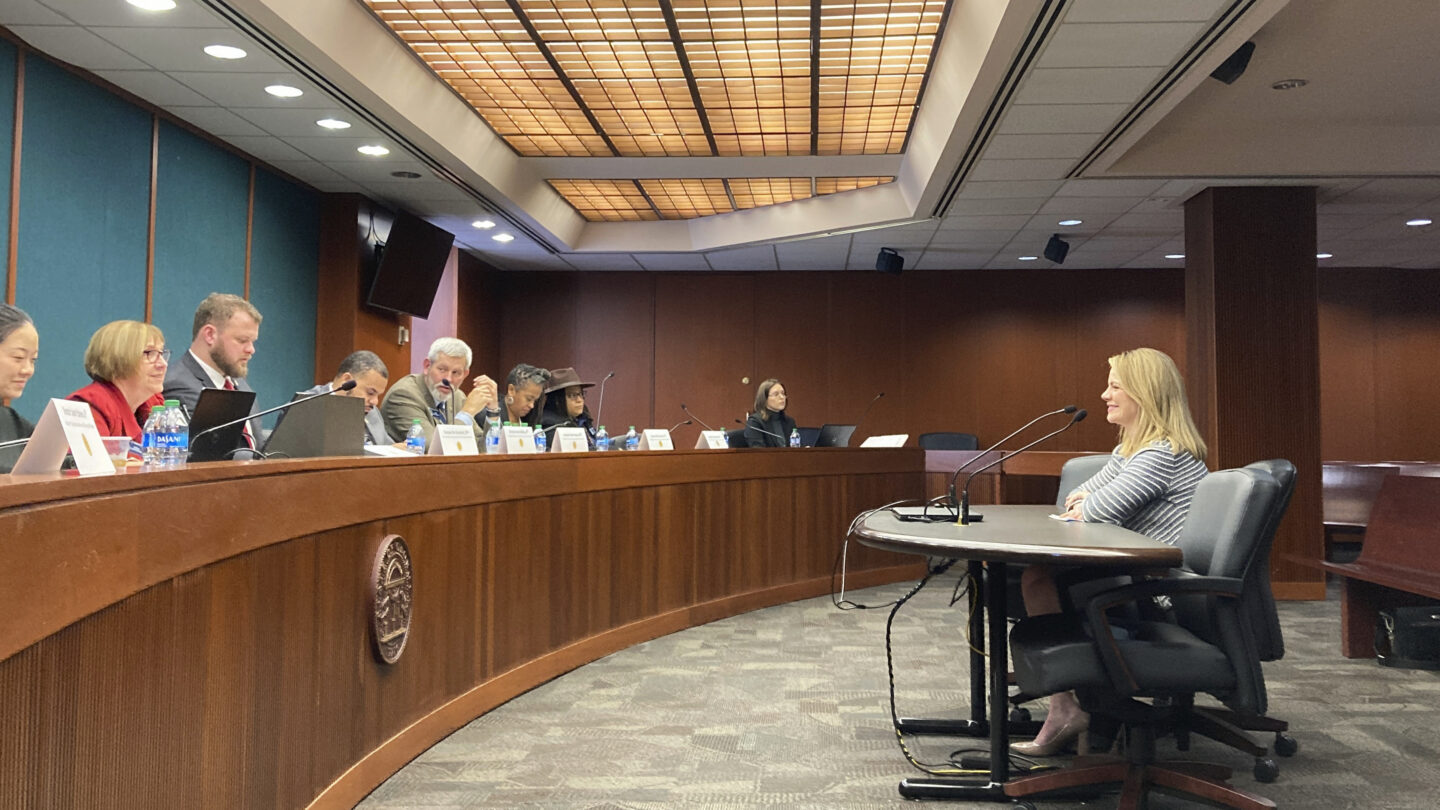

The Senate Children and Families Committee held a hearing Thursday on Senate Bill 133 but did not vote on the measure, saying it needed more work.

The bill would not impose new requirements on ordering children into state custody when a judge finds a parent or guardian is neglecting or abusing a child.

Despite those protections, some lawmakers said they were worried about slowing down the process.

“If a child is in immediate danger, my question is whether we can speed up this process to remove them from immediate danger,” said Sen. Nikki Merritt, a Lawrenceville Democrat.

Human Services Commissioner Candice Broce told the committee the changes “will have a direct and immediate impact on keeping children newly entering our custody from being temporarily placed in any hotel or office.”

Dozens of Georgia’s most troubled foster children end up in hotels or state offices each night because the state Division of Family & Children Services can’t find a better place for them to stay.

The measure would impose new requirements on juvenile court judges before they could order children into state custody when they find a child is in need of services, called a CHINS case, or delinquent.

“Senate Bill 133 ensures that there’s an opportunity for DFCS and the parties to the delinquency of CHINS case to make efforts to avoid a child coming into the foster care system unnecessarily,” Broce said.

Juvenile court judges would be required to ask what services have already been provided to children and parents and what services could be provided to let children remain at home. It would also require the judge to confirm there’s no other custody placement available except with the state.

Child welfare officials would have to be notified of custody hearings and allowed to be present.

A judge couldn’t put a child in state custody unless the judge finds the division “has been provided a meaningful opportunity to make reasonable efforts to avoid the removal of the child from his or her home,” and the division could ask to put off a decision for 24 hours “to make reasonable efforts” to keep a child out of foster care.

The division would get a chance to review all medical, psychological and educational assessments pertaining to a child or parents before assuming custody. The court would be required to order any records that parties to the juvenile court case don’t have in their possession be given to child welfare authorities.

“Getting that information for the agency has been extremely difficult,” said Sen. Derek Mallow, a Savannah Democrat.

Broce said the changes would “establish a more uniform process” for the state to take custody. She and other state officials have said that too often, judges order children into custody without notice, and social workers know nothing about a child’s needs.

Child advocates say they support the emphasis on family preservation, saying that providing more services before a crisis would prevent more foster care cases and avoid children staying in hotels.

Officials have testified that the practice of hoteling has other underlying causes, including fights over payment with the state’s own insurer and a lack of psychiatric treatment beds. Hoteling typically costs the state $1,500 per child per night, ties up social workers, and denies children a stable environment and needed treatment.

“It’s a system problem, it’s been decades in the making, but it’s going to take all of us to solve it,” said Polly McKinney, advocacy director for Voices for Georgia’s Children.