Georgia Department Of Health Apologizes For Weekend Data Snafu

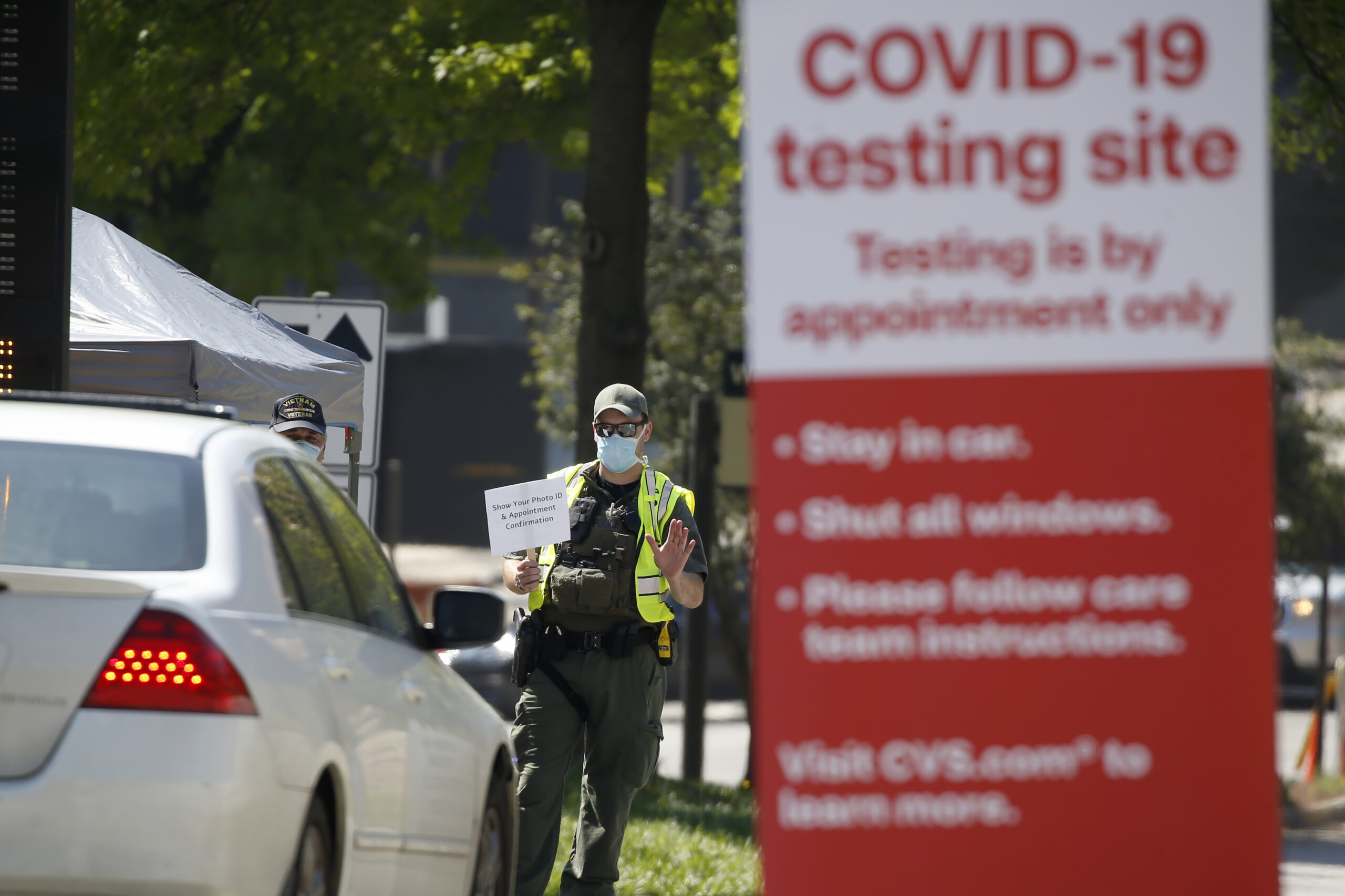

A police officer directs cars into a coronavirus testing facility at Georgia Tech last month in Atlanta.

John Bazemore / Associated Press

The Georgia Department of Public Health is apologizing for a processing error that caused the number of COVID-19 cases to decrease at some point over the weekend.

In a tweet, DPH said it inadvertently included 231 serologic test results among the positive cases.

Serologic tests are blood tests that look for antibodies and are used to find out how many people have had Covid-19 by.

DPH said results from these tests are considered probable and not included in their confirmed totals.

As a result of the error, COVID-19 cases in Georgia suddenly decreased between reporting periods as officials realized their error.

It’s not the first error in Georgia’s reporting. Gov. Brian Kemp’s issued an apology last week after DPH released a graph that appeared to show cases in the most affected counties dropping every day for two weeks. That misleading impression was caused by reordering dates on the chart.

The x axis was set up that way to show descending values to more easily demonstrate peak values and counties on those dates. Our mission failed. We apologize. It is fixed.

— Candice Broce (@candicebroce) May 11, 2020

DPH said in an email that test results are reported to them “via the electronic laboratory reporting (ELR) system in the State Electronic Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (SendSS). It is the same system we use for all notifiable disease and conditions.”

Currently, they said, they’re getting data from 127 health care systems, hospitals, laboratories and other facilities.

WABE has reached out to DPH with more questions about Georgia’s testing data and is awaiting answers.

If you have questions about testing or data, send them to covid19@wabe.org. Until we hear back from DPH, here is some advice from NPR on how to read COVID-19 data points:

Total Confirmed Cases

What we want this to tell us: How many people have had COVID-19.

What it actually tells us: How many people have tested positive for the live virus (the most common way of being diagnosed) or, in some cases, been diagnosed based on symptoms. The actual number of people who have had COVID-19 is probably higher.

Caveats:

- Access to testing is limited in many parts of the world, so not everyone with COVID-19 symptoms is confirmed and counted.

- Official counts of “confirmed cases” miss people with no symptoms or mild symptoms who may not seek testing or medical care.

- The swab tests are considered to be generally reliable but aren’t fail-safe — there’s a margin of error from mistakes in sampling or lab processing techniques as well as from faulty tests.

Daily Case Counts

What we want this to tell us: Is the number of new cases of COVID-19 rising or falling over time?

What it tells us: How many cases are reported on each day, and how that number compares to previous days. Only in areas where large numbers are tested regularly could the curve of daily case counts be considered a reliable marker of spread or containment.

Caveats:

- Testing delays and backlogs in many countries means that a case may be reported days or weeks after a sample was taken. It can also take a few days for a confirmed case to be reported to national and global health authorities. So the number of new cases reported on a specific date may reflect both new and recent cases rather than the new case count on one specific date.

- Countries don’t always use the same definition for “confirmed cases,” and some have changed their criteria as the pandemic has evolved. On April 14, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began including people presumed to have COVID-19 based on symptoms in their daily tally of confirmed cases even if the individuals had not been tested. China has revised its case definitions for infected people multiple times, briefly including diagnosis by symptoms in one province, then returning to a requirement for a lab test to confirm.

Total Deaths

What we want this to tell us: How many people have died from COVID-19 from the start of the outbreak until now.

What it tells us: How many people have died with the official cause of death listed as “COVID-19” — excluding those who died of the disease but were not identified as COVID-19 casualties. These numbers generally represent a conservative count of deaths and will likely be revised upward on review. But they are probably more accurate than case counts. “The [under]reporting issue for death numbers is less severe than case numbers, but it still exists,” says Sen Pei, a public health research scientist at Columbia University.

Caveats:

- As with testing, issues with varying definitions and delays in reporting also apply to deaths. In Wuhan, China, for example, where the first COVID-19 cases were discovered, the death tally jumped by 50% overnight in mid-April. WHO says this is because a review of past records found 1,290 deaths had been missed in the official count due to patients dying at home, medical staff too busy to fill out paperwork at the time and incomplete reporting from field hospitals.

Death Rate For Coronavirus Patients

What we want this to tell us: How likely are people who get COVID-19 to die from it?

What it tells us: The total number of reported deaths divided by the total number of confirmed cases — both of which could be undercounts.

Caveats:

- In the middle of an epidemic, the death rate changes day-by-day based on the number of reported cases and deaths. Death rates could decrease over time as more survivors are identified.

- It’s difficult to meaningfully compare death rates across countries because of variable factors including the extent of testing and the demographics of the population (countries like Italy, which have a greater proportion of older people, have seen high death rates).

Recovery Rate For Coronavirus Patients

What we want this to tell us: How many people who have contracted COVID-19 recover.

What it tells us: How many people who have been officially diagnosed with COVID have kicked the virus.

Caveats:

- The number of confirmed cases may be missing many people with mild cases, who tend to recover — so the total count of recovered people is probably higher.

- The definition of a recovered case varies — the World Health Organization states there should be two negative tests at least 24 hours apart while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offers a symptom-based definition in places where tests are not readily available. Neither definition takes into account long-term physical and mental health effects, such as reduced lung function from scarring or memory issues from treatment drugs, especially in people who have recovered from severe cases.