Georgia Initiative Brings Business To The Table To Save A Rare Animal

Gopher tortoises are a keystone species. Scientists have found about 350 different species that live in the burrows the tortoises dig.

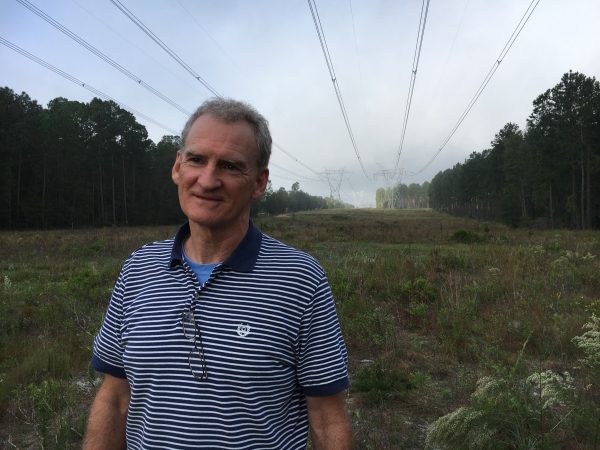

Randy Browning / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Gopher tortoises are big, dry, wrinkly reptiles that dig burrows underground in the parts of Georgia where the soil is sandy, down South and near the coast.

To the people who study them, they’re “cute,” “quite personable,” and “just a great little critter.” To the 350 or so other species of animals that use their burrows, they’re property developers. And to businesses, they’re a potential problem.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering protecting gopher tortoises in Georgia under the Endangered Species Act. Gopher tortoises are already protected by the state of Georgia, but the federal Endangered Species Act is more stringent than the state law. A federal listing can be bad for business, since protected species can mean red tape and additional costs.

In Georgia, instead of fighting the potential listing, businesses are working with wildlife agencies on what’s called the Georgia Gopher Tortoise Initiative, to save the gopher tortoise – before they’re forced to by federal regulation.

Looking For Tortoises

Aisha Favors walks in straight lines, back and forth, in a patch of longleaf pine forest on the property of Georgia Power’s nuclear Plant Hatch. She bushwhacks past spiky palmetto plants and fall-blooming goldenrods. The light trickles down between the tall trees.

Favors, who works for the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, is looking for piles of sand made by gopher tortoises as they dig their burrows.

“It’s a numbers game,” she says. “Just hoping that you find one. But when you do, oh, it’s so much fun.”

Favors doesn’t turn up any tortoises on this patch of forest, but nearby, at another spot on Plant Hatch property, the DNR gopher tortoise team does find some.

Savannah McGuire crouches next to a gopher tortoise burrow, getting ready to snake a camera down into it. The camera will stream video on a monitor up above ground, so she can see what’s in the burrow.

“We’ll stick it down the burrow and see if he’s home,” she says.

The tortoise McGuire finds is about a foot wide and about 40 years old.

Fixtures On The Landscape

“I consider them like a fixture on the landscape,” Kurt Buhlmann, a senior research scientist at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Lab, says of adult tortoises. “They’re like a rock. They’re going to be there.”

But there are fewer than there once were. Buhlmann says tortoise numbers have dropped partially because of habitat loss.

The longleaf pine forests where the tortoises thrive have given way to tree plantations, development, and solar farms. The wildfire that keeps longleaf pine healthy has been suppressed. There was once about 90 million acres of longleaf pine in the Southeast. Now there are more like 3 million acres.

The tortoises also have a legacy problem. During the Great Depression, people ate them. They were nicknamed “Hoover’s chickens.” Because gopher tortoises live so long, they still haven’t bounced back, almost a century later.

The Gopher Tortoise Initiative is working to address that, by finding healthy gopher tortoise populations – whether they’re on public land or private property – and protecting them where they are. Voluntarily, without federal regulation.

Nuclear Neighbors

“We’re glad to have them here,” says Georgia Power wildlife biologist Jim Ozier, standing under the high-voltage transmission lines running from Plant Hatch. “Gopher tortoises do very well right next door.”

‘There’s always a perception that business and industry and conservation groups are at loggerheads, that we don’t agree on anything.’

— Doug Miell, Georgia Chamber of Commerce

Ozier says in addition to planning around the tortoises, to make sure they’re not affected by transmission line maintenance, Georgia Power plans to bring fire back to the woods next to the power lines, in the form of controlled burns, to restore the longleaf pine savannah that would have grown here naturally.

“It is a slow process, and I’ll never see the end results of it, but feel good knowing it’s heading in that direction,” he says.

‘Conservation Without Conflict’

The federal government isn’t just the stick in this conservation carrot-and-stick scenario. The federal government is putting $50 million into the Gopher Tortoise Initiative. The state Department of Natural Resources and private foundations are each raising an equal amount, too, with the Georgia Chamber of Commerce as a partner in the project

‘If you can do something to avoid the conflict, or even the need to list, that’s a much better result.’

— Don Imm, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

“I recently heard that our new Secretary [of the Interior Ryan] Zinke is all about conservation without conflict, and this is clearly an example of that,” says Don Imm, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife field supervisor in Georgia.

Imm says if the science indicates that gopher tortoises should be federally protected, then they will be. But, he says he thinks, “if you can do something to avoid the conflict, or even the need to list, that’s a much better result.”

It’s better for businesses, too, says Doug Miell, a consultant with the Georgia Chamber of Commerce.

“There’s always a perception that business and industry and conservation groups are at loggerheads, that we don’t agree on anything,” Miell says. “This is a good example of where we can come together to demonstrate that, hey, we might be looking at it from different sides, but the outcome is the same.”

‘Everybody has the same goal. Even if it’s just to make sure they’re not listed, in the end that means effective conservation for tortoises.’

— Tracey Tuberville, UGA Savannah River Ecology Lab

Tracey Tuberville is an associate research scientist at UGA’s Savannah River Ecology Lab (and happens to be married to UGA’s Buhlmann; neither of them are involved in the Georgia Gopher Tortoise Initiative). She says it’s great that the partners in the initiative are working on restoring the land, but, in some cases, it’s better to go a step further and actively reintroduce rare species. That’s what her work focuses on.

Still, she says what the initiative is doing gives her hope for gopher tortoises.

“I actually am very optimistic that they are a species you can recover,” she says. “Everybody has the same goal. Even if it’s just to make sure they’re not listed, in the end that means effective conservation for tortoises.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of acres of longleaf pine that used to be in the Southeast. There were about 90 million acres.