Georgia launches new grant portal ahead of opioid settlement distribution

Georgia has established a new trust for distributing the hundreds of millions of dollars headed to the state from the nationwide settlement with opioid drugmakers and distributors.

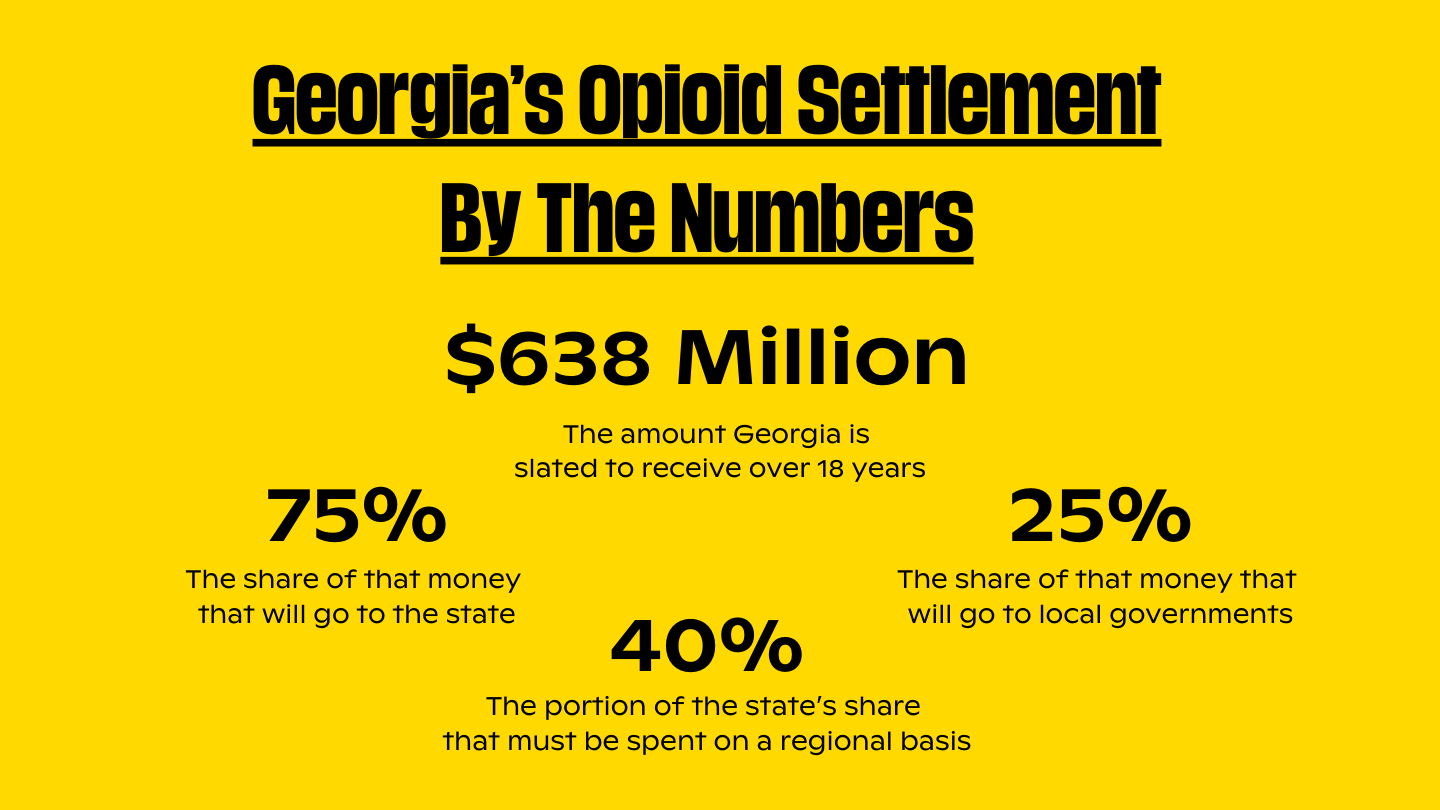

Georgia’s overall share of the settlement is pegged at least $638 million over the next 18 years.

The money has already begun flowing into the state. Now, the task of spending it begins.

Under the terms of a previously released memorandum of understanding, Georgia must spend the funds on prevention, treatment, recovery and harm-reduction efforts. It can also be used for research and education programs.

Approximately 25% of the total funding will go directly to local participating governments. The other 75% –– around $479 million –– will be distributed by the trust.

“Nothing can be done in return to return those we lost to the opioid epidemic. What we can do, what we must do, is work together to provide the means to end this crisis,” said state Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities Commissioner Kevin Tanner, who is the new Opioid Crisis Abatement Trust trustee.

Community organizations and local governments around the state can apply for grant funding from the trust beginning April 15.

At a workshop near the state Capitol building that attracted more than 100 would-be applicants, Tanner and two other officials outlined the application process.

In the initial round of applications, groups will be able to apply for funding for a single year, or up to two years, Tanner said.

“Obviously our goal is to get these funds on the street and to be able to start seeing progress quickly, as quickly as we can, at the same time making sure the funds are used properly,” he said.

Georgia’s opioid overdose deaths increased by 207% between 2019 and 2020, according to the state Department of Public Health, following more than a decade of steady increases, driven largely by fentanyl.

“Fentanyl is a continued issue. And it’s not just fentanyl mixed with heroin, it’s fentanyl that’s in almost every drug that’s in the market right now. Even something as simple as marijuana may have fentanyl mixed in it,” said Cassandra Price, director of the Office of Addictive Diseases at the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities. “So we’re seeing overdoses and drugs that typically are not high overdose rates.”

Read more about the nationwide opioid settlements at KFF.

Georgia’s policy document specifies that settlement funds are spent on “approved purposes.” The state can request documentation from recipients for any funding it suspects is being used for a non-approved purpose.

“The settlement agreements between the lines imply that the political process, on the part of the state, will largely control the nature and texture of opioid settlement spend,” said attorney Christine Minhee, founder of the project OpioidSettlementTracker.com, which monitors and analyzes opioid settlement spending across the country. “And the decision to give moneys to governments and to prioritize public litigants over the private ones is of huge concern and debate.”

The agreement mandates that local governments establish advisory councils to help determine opioid settlement spending in their areas. Each council must include a member from a participating county’s board of health, an executive team member of a Community Service Board, and a sheriff’s department representative.

The statewide Georgia Opioid Settlement Advisory Commission members are:

- David Dove, executive counsel

- Xavier Crockett, Georgia Department of Public Health director of the Division of Health Protection

- Cassandra Price, director of DBHDD’s Division of Addictive Diseases

- Gary Sisk, Catoosa County sheriff

- Grant Thomas, Gov. Brian Kemp’s director of the Office of Health Strategy and Coordination

Catoosa County Sheriff Gary Sisk said he’s in discussions with other law enforcement and government officials in his area about how they could potentially collaborate with a regional approach to bringing in more addiction-treatment options, caseworkers and prevention resources.

Roughly three-quarters of his small northwest Georgia county’s jail population is locked up on charges related to the opioid epidemic, Sisk said.

“It doesn’t mean that they’re in there on drug charges. Could be they’re stealing from family members or committing other crimes because they can’t hold a job to satisfy their addiction. And our biggest issue I’m seeing is really wanting to target those young people and educate them,” he said. “Prevention could be so much greater. If we could really, really get in there and make an impact with those young people. Because once somebody gets hooked on the drugs, it’s 10 times harder to get them to turn around. Then, if we could get them before they ever get to that point, then maybe we could make a greater impact.”

Georgia’s settlement plans require an annual report on spending that includes the allocation of any approved funding awards, recipients, programs funded and disbursement terms.

The report is also required to include an assessment of how well settlement funding has been used to abate opioid addiction, overdose deaths and other consequences of the opioid crisis.

Officials are planning future workshops for potential applicants in Macon, Brunswick, and Columbus soon.

See more at Opioid Crisis Abatement Trust.