Georgia Piecing Together Network Of Protected Wild Lands

The Conservation Fund bought the Sansavilla property in 2014, and has been restoring it as it’s transferred the land to the state of Georgia.

Stacy Funderburke/The Conservation Fund

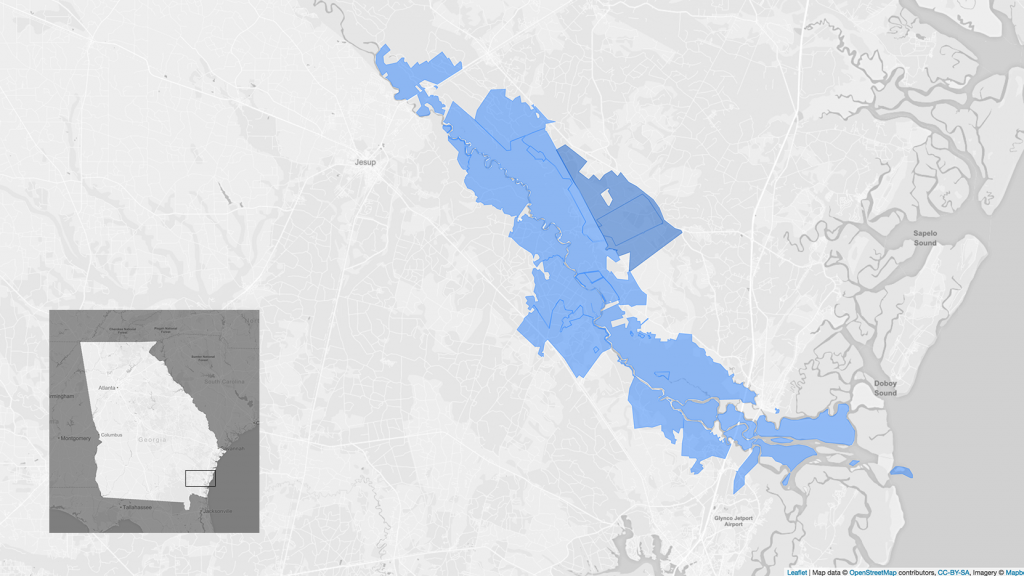

Georgia’s Altamaha River is big. It’s one of the largest flowing into the Atlantic Ocean on the eastern seaboard. Over the past couple decades, piece by piece, the state of Georgia has bought up land along either side of it, creating a network of protected forests, marshes and streams called the Altamaha River Corridor.

The state recently acquired a large chunk of property, closing a gap in the corridor. Earlier this fall, about 50 people made their way miles up a dirt road past tree farms, to celebrate the addition of the 17,000 acre-Sansavilla Wildlife Management Area.

Behind the podium, ceremonial ribbon, and pile of scissors, the pine trees opened up to a high bluff and the Altamaha River curving below.

“Atlanta’s got new Mercedes-Benz stadium. Atlanta’s got SunTrust Park, but does Atlanta have anything that looks like this?” Georgia Forestry Commission director Chuck Williams asked the crowd at the event.

“Let’s give the Altamaha a hand,” he said, to applause.

Environmental groups and federal agencies are helping the state piece this corridor together.

So is the U.S. Department of Defense.

The marines are expanding the nearby Townsend Bombing Range. Even though the practice bombs they drop don’t actually explode, they still don’t want people and businesses moving in around them.

“By establishing this piece of land as a buffer, that allows us to train fully where we need to train,” said Colonel Timothy Miller, the commanding officer at Marine Corps Air Station Beaufort.e.

Miller says it’s a win-win. The Marines get to grow, and they’re helping the state expand and restore the protected areas.

Restoring Longleaf

The land at Sansavilla used to be a pine plantation. Now, it’s being turned back into the forest that would have grown here naturally.

“Those little trees springing up through there are longleaf pines we have planted,” said Jason Lee, with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Longleaf pine trees used to cover more than 90 million acres of land in the Southeast. Now, Lee says, it’s just 3 million acres.

“It was a really prized forest,” he said. “From early colonial accounts, it was just beautiful, breathtaking, sort of more savannah than forest, real open big pine trees.”

But those trees were cut down. Lee says the longleaf pines didn’t grow back very well on their own.

“One of our primary goals for the state of Georgia – and for a lot of states in the Southeast – is to restore as much longleaf habitat as possible.”

Moving Along The Corridor

Since Sansavilla is part of a larger corridor of protected landscapes, that helps animals, says Lee.

“It’s what we call protected and connected, and that way critters can move back and forth and up and down and around this corridor.”

Lee says the idea for the Altamaha Corridor has been around since the 1970s, but it really took off in the mid-90s.

Eventually, it will link with the Okefenokee Swamp, to the south, and the protected corridor already stretches 40 miles east, along the river to the Atlantic Ocean and Georgia’s barrier islands.

“We’re right at the mouth of this phenomenal river system,” said Scott Coleman, ecological manager of Little St. Simons Island.

Standing on neighboring St. Simons Island, looking across the Altamaha Delta, Coleman sees fiddler crabs, shore birds, and a pair of mink. It’s totally different from the pine trees at Sansavilla, but Coleman says this landscape benefits from the land upstream being protected.

As sea level rise affects the Georgia coast, the corridor plays another role.

“When you have land like this protected – high ground protected – adjacent to a salt marsh, then you can imagine this marsh sort of marching up this bank in time,” says Coleman.

Rising seas will push the marsh inland. It can’t move into a city, like Brunswick, but the marsh can move up the corridor.

“Any time we can protect high ground or property adjacent to our coastal areas, we’re enabling our systems to be more resilient,” he says.

Georgia wildlife officials hope to make protected land all over the state more resilient, by continuing to expand corridors – even into neighboring states.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the number of acres of longleaf pine that used to be in the Southeast. There were about 90 million acres.