Giving Back: Immigrant Doctors Helping Immigrant Patients In Georgia

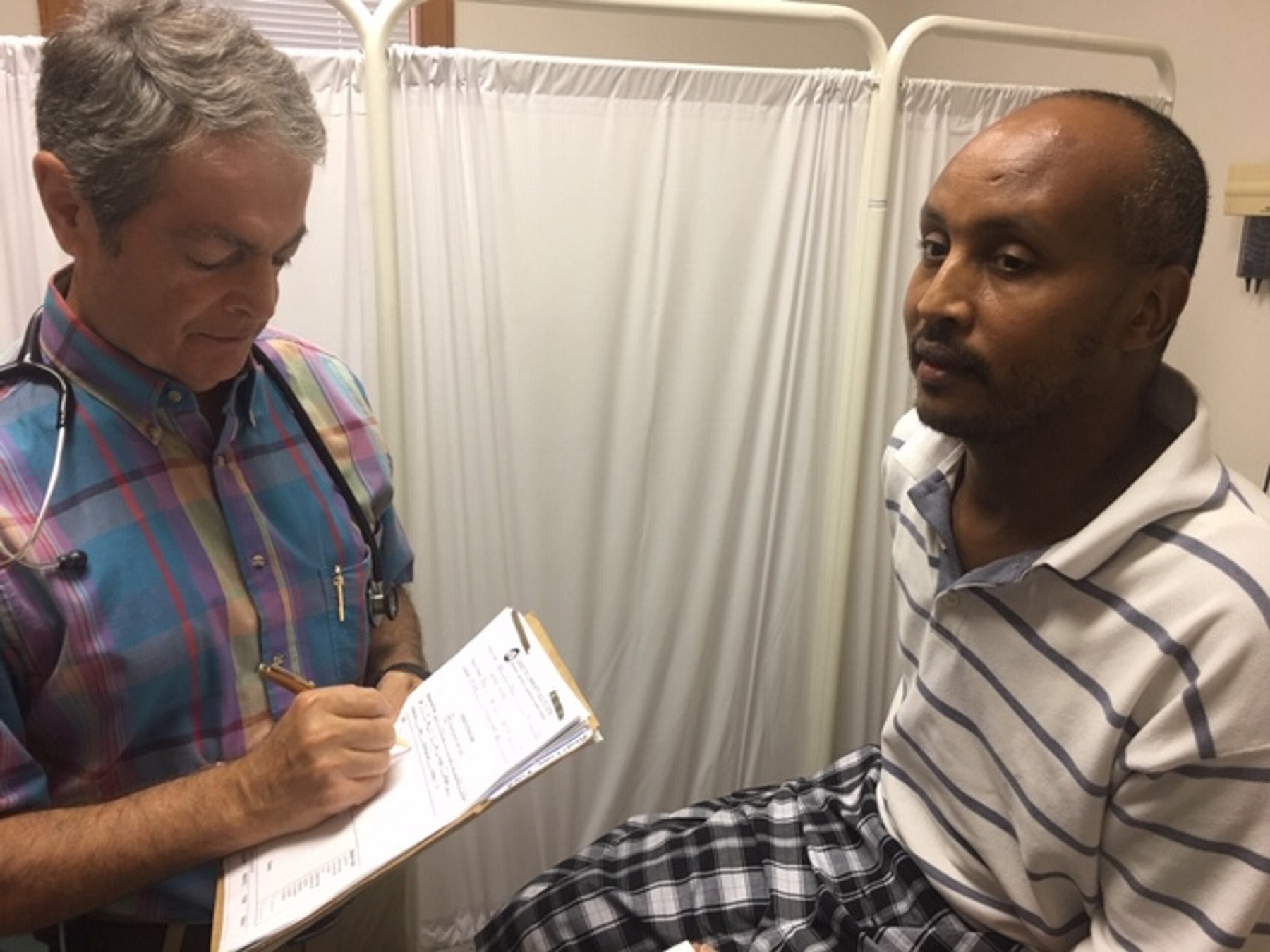

Syrian-born Dr. Omar Akhras treats Fuad Abdi Limo at the Clarkston Community Health Center. Foreign-born physicians supply a surprising amount of medical care in Georgia and the U.S. Most of the doctors at the Clarkston clinic are foreign-born and volunteer their time on Sundays to treat patients, including dozens of immigrants, refugees and migrant workers.

Courtesy of Georgia Health News

This is the third in our series on foreign-born physicians practicing in Georgia. Part 1 focused on Indian-born doctors in Georgia, and Part 2 detailed obstacles that physicians face in order to practice here.

Lower back pain and diarrhea brought Fuad Abdi Limo to a DeKalb County clinic founded to treat people just like him.

Abdi Limo, a political refugee from Ethiopia, described his medical problems in Amharic, that country’s main language, to an interpreter, who then relayed the answers to Dr. Omar Akhras.

The physician listened intently, then discussed through the interpreter how to prevent back problems. Akhras told Abdi Limo, who lifts boxes at a chicken company, that he needs to squat when bending down to pick up objects. “The knees are meant for that.” For the other problems, Akhras ordered tests, including a urinalysis.

Akhras, 68, has a primary care practice in Hancock County. But he’s also a regular volunteer several counties away, at the Clarkston Community Health Center. Every Sunday, dozens of immigrants, refugees and migrant workers come there to get medical, dental and other care. The clinic is located in Clarkston in DeKalb County, a town known as a haven for refugees.

Most of the volunteer doctors at the clinic are foreign-born, like Akhras, who came to the U.S. from Syria to do his medical residency in Atlanta.

Clarkston clinic co-founder Dr. Gulshan Harjee, a longtime DeKalb internist who was born in Tanzania, says of the volunteer immigrant physicians: “This is a passion for them. They want to give back. They feel it’s payback time.’’

And it’s not just in free clinics: Foreign-born physicians supply a surprising amount of medical care in Georgia and the U.S.

The American Medical Association says that as of last year, 18 percent of practicing physicians and medical residents in the U.S. were born in other countries. Georgia’s percentage of foreign-born doctors is similar, at 17 percent.

Why such a high percentage?

The U.S. is in a physician shortage that’s expected to balloon to up to 120,000 physicians by 2030, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. Even now, primary care doctors are relatively scarce in certain areas of the country. Georgia itself has a few counties without any doctors at all, and many counties lack a pediatrician or an OB-GYN.

Foreign-born physicians help fill the gaps, especially in primary care. There are not enough American-born doctors to supply that need, says Dr. William Salazar of Augusta University’s Medical College of Georgia, who came to the U.S. from Colombia.

Rural Georgia has a higher percentage of immigrant doctors than urban areas, says Jimmy Lewis of HomeTown Health, an association of rural hospitals in Georgia.

“Foreign-born doctors go to places no one wants to go,’’ Harjee says.

Options For Medical Services

Once they arrive here, immigrants enter a patchwork system that offers several entry points for care.

Many eventually are assimilated into the regular insurance system, going to private physicians’ offices or hospital-owned primary care centers for medical services. But others have no coverage.

One option is community health centers, also called Federally Qualified Health Centers, which see many immigrants, especially in areas of the state where agricultural workers need care, says Duane Kavka of the Georgia Primary Care Association. But it’s not just rural. An FQHC in suburban Norcross, the Center for Pan Asian Community Services, treats many Asian immigrants.

Some medical services are sponsored by immigrants’ places of worship.

And free clinics offer another choice, including Good Samaritan Health Center of Gwinnett, a populous county northeast of Atlanta where one in three adults is an immigrant. Up to 3,000 a month seek services at “Good Sam,” with the majority of patients being Hispanic, said Greg Lang, executive director. Most of that patient group are either citizens, on a visa or on a work permit, Lang said. Much of the staff is foreign-born.

Other charitable clinics also see high numbers of immigrants, such as those working in poultry businesses in Gainesville and the carpet industry in Dalton.

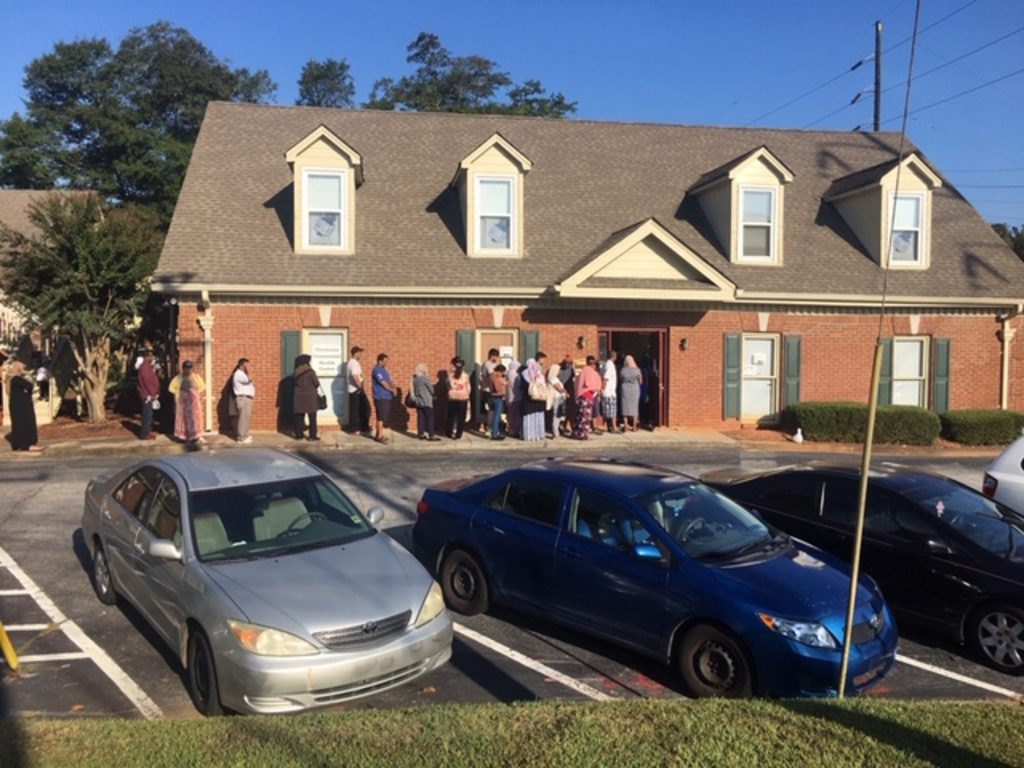

At the Clarkston Community Health Center, patients begin showing up before dawn on Sundays, waiting in line outside.

Once the clinic opens, rows of chairs quickly fill with people waiting to be seen. An open area of the building is jammed with a mix of Emory medical students, interpreters and others helping move patients into exam rooms.

About 75 percent of the patients are immigrants, refugees or migrant workers. Up to 30 languages are spoken there. Harjee says she speaks “only six.’’

Sameera Vadsariya, 37, says through an interpreter that she loves the services there. She was born in India, and is here on a visa. She has no health insurance, so the free services are worth the long wait for treatment for a cold and fever.

This is a passion for them. They want to give back. They feel it’s payback time.

Dr. Gulshan Harjee says of the doctors who volunteer their time at the DeKalb clinic

Many immigrant patients prefer to see physicians like them, says Saeed Raees, a Pakistani-born pharmacist who co-founded the Clarkston clinic. Even people who gain private insurance “prefer to come here,” Raees says. “We see everybody and anybody.”

While the Clarkston community is friendly toward people from other countries, others in Georgia may not be as welcoming.

“The general atmosphere is not very positive toward immigrants,’’ Akhras says.

Critics say Georgia politics occasionally reflect this attitude. The state Legislature has considered legislation in recent years that opponents have called “anti-immigrant.’’ And GOP candidates for governor campaigned in their primary this year about cracking down on illegal immigrants.

Raees says that “you’ll run into a small minority who don’t want to be seen by a foreign-born doctor or a Muslim doctor.”

The prevailing sentiment toward foreign-born physicians, though, has changed over the years, says Dr. Susana Alfonso. She practices family medicine in Atlanta and is a faculty member at Emory School of Medicine.

Alfonso was born in Ecuador, and came here at age 6 when her parents, both physicians, moved to Georgia.

“They faced a lot of barriers,’’ Alfonso says. “They were first-generation immigrants, and the immigrant community was smaller then. There was a lot of prejudice by patients toward my parents.”

She hasn’t faced that, she says. Most of her patients are Hispanic, Alfonso says, and speaking Spanish and having cultural understanding helps many foreign-born doctors like herself connect with these patients.

That’s also a familiar theme in the Korean community. Dr. Song Na, an internist in private practice in Buford, in suburban Atlanta, says most Korean immigrants prefer “someone they’re comfortable with.’’ Na, who was born in South Korea, says that while his practice is only 5 percent to 10 percent Korean patients, other Korean-born doctors see a much higher number of patients from that country.

There can be some awkwardness in dealing with patients of other backgrounds, says Salazar of Augusta, who is trained as an internist and psychiatrist.

“When they think you’re different, they think you’re not as smart, and think they won’t understand what you’re saying,” He says. “You develop skills to overcome that.’’ Patients, overall, are getting used to people from other countries, he says.

Salazar has a high number of immigrants in his Augusta University practice. And he has helped start a free clinic that serves mostly people from other countries, especially Hispanic patients. “I really believe that our responsibility as citizens of our country is that we should provide community services to the poor and underprivileged.”

Diabetes afflicts a large share of Hispanic people, and many diabetes specialists here are also foreign-born, says Dr. Guillermo Umpierrez, chief of diabetes and endocrinology at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta.

Besides his Grady clinical work, teaching and research, Umpierrez, who was born in Ecuador, heads a diabetes education program for Latino patients, training physicians and nurses in this care as well. “We have educated a few thousand Hispanic patients throughout the state of Georgia,’’ he says.

Foreign-born physicians, Umpierrez says, “will play a significant role in filling the [doctor] shortage. I think foreign-born physicians will play an even larger role’’ in U.S. health care.

‘Controlled Chaos’

The Clarkston clinic is stuffed into an office building near the railroad tracks that cut through the town. The 2,500-square-foot area can barely handle seating for the patients. Restrooms double as cleaning supply storage areas. Two closets hold prescription drugs. “It’s controlled chaos,’’ as one staff member puts it.

Many patients have never seen a dentist, Harjee says, pointing to the two dentist chairs tucked inside a room. Also offered is a women’s clinic, later on Sundays; an eye clinic; a mammography van once a month; and mental health services.

The total budget: $100,000.

“Is there anywhere in this country where you can provide this much care for that much money?’’ Harjee asks.

Another clinic leader is Dr. Arshed Quyyumi, an Emory cardiologist, who was born in India and grew up in England. He says that clearly there was a need for such a service.

“It’s growing exponentially,’’ he says. “We need a bigger building.”

Elisabeth Aregay, who was born in Ethiopia, brought her mother, Adugna Gudeta, to the clinic for a follow-up. “They check everything,’’ says Aregay, who has no health insurance.

Paying out of pocket can cost hundreds of dollars, so the Clarkston clinic helps patients save money. “I want to say, ‘Thank you,’ ” Aregay says.

Read other stories in our series:

Part One: Doctors born in India fill medical gaps in Georgia

Part Two: Trained to be a doctor, but held back by red tape

Andy Miller is editor and CEO of Georgia Health News