How FEMA Uses Waffle House To Measure Disasters

When a big storm or tornado devastates a community, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) usually steps in to help state and local officials. But in recent years, FEMA has been getting some help of its own from an unexpected source – one you see on almost every highway throughout the Southeast: Waffle House.

During a busy lunch hour at a Waffle House in Norcross, Ga., manager William Palmer grills up a Texas Lover’s BLT for one of his customers on the high counter.

But there were a couple of days January 2014, where this Waffle House was packed to the brim. It was during the ice storm that paralyzed the metro Atlanta area, and Palmer says people took refuge here.

“A lot of people were stranded on the highway with cars and they couldn’t get to their cars,” Palmer said. “But since we’re a staple in the community, they always knew they can come here and get great service and great food.”

Palmer and his employees worked shifts around-the-clock as the city thawed – the company put him and other employees up in hotel rooms nearby.

“My day was pretty long,” he said. “Basically make sure the customer area was safe, make sure we iced the road, and just make sure everything was great for the customers.”

The 24-hour restaurant chain prides itself on serving its customers at all hours of the day, seven days a week. And FEMA caught on to this. They discovered that if a Waffle House was closed after a storm, then that meant things were really bad.

“It just doesn’t happen where Waffle House is normally shut down,” said Philip Strouse, FEMA’s private sector liaison for the Southeast.

Strouse said Waffle Houses are able to bounce back relatively quickly after a natural disaster, and have a good sense of what their statuses are in a community.

“They’re sort of the canary in the coal mine if you will,” he said.

In 2011, the current head of FEMA, administrator Craig Fugate, was said to have coined what’s called the Waffle House Index. There are three measures in the index: green, yellow and red.

Green means the restaurant is open as usual, yellow means it’s on a limited menu, and red means the restaurant’s closed.

The index isn’t necessarily scientific, Strouse said, but it allows FEMA to know quickly about how things are on the ground.

“It gives us a pretty good feel right away when, of course, there’s the fog of trying to figure out what’s going on,” he said.

Because Waffle Houses restaurants are in areas prone to hurricanes and tornadoes, the company has made it part of their business plan to be prepared, said Pat Warner, the vice president of culture at Waffle House.

“We all have, what I call, ‘day jobs’ and then when the crisis comes, we all kind of stop,” said Warner, who’s also part of the company’s disaster management team.

For example, the man who handles restaurant operations also monitors the weather during hurricane season. The company starts tracking storms when they’re still a tropical depression, Warner said.

Every employee also has a copy of the company’s hurricane playbook, which has instructions on how to respond during a crisis. If a storm’s on its way, Warner said the company will rent generators and start sending teams to the area.

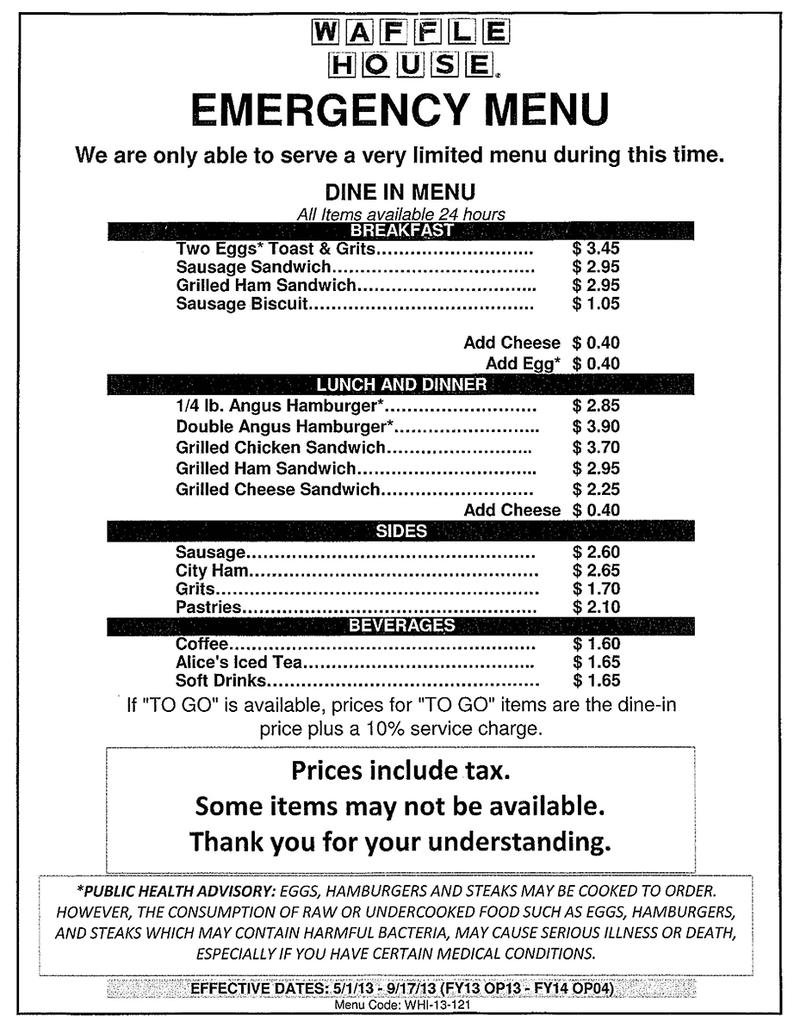

Waffle House even has an emergency menu, pared down for quick production and efficiency.

“Unfortunately for bacon folks, bacon takes up too much grill so we do sausage instead of bacon,” Warner said.

Waffles are not on the menu either, because they take too much electricity to make.

“From the standpoint of an engineer, the hurricane menu makes absolute sense,” said Julie Swann, associate professor of industrial and systems engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology and co-director of the Center for Health and Humanitarian Systems.

She said she uses Waffle House as an example of how to use limited supplies for maximum benefit for other disaster management agencies.

“What we found in discussions with [Waffle House] is that they really considered responding to emergencies part of their core mission to meet the needs of customers,” Swann said.

Back at the Waffle House in Norcross, that’s what manager William Palmer is focusing on today – meeting the needs of customers.

But he said if the next disaster strikes, he’s not worried.

“We’re ready for it,” Palmer said.

And FEMA will be watching.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))