How Georgia Supreme Court justices get selected, decide cases and more, explained

State supreme courts have been making headlines nationally for ruling on controversial topics. Recent notable rulings include the Alabama Supreme Court’s decision that frozen embryos are considered people, and the Colorado court’s attempt to remove Donald Trump from ballots.

In Georgia, the court upheld a six-week abortion ban last year and declined to approve rules for a GOP-backed commission to discipline prosecutors.

Supreme courts have historically been recognized as apolitical. But decisions on hot-button topics are energizing partisan politics on a national level.

Still, Georgia’s highest judicial body has remained elusive. Most of the cases it considers are criminal appeals.

In this year’s election, four Georgia justices are on the ballot, but so far there’s only one contested race. That’s typical for the Court, in which elections are often inconsequential.

Here’s everything you need to know about the Georgia Supreme Court, from the types of cases it hears to how justices are appointed.

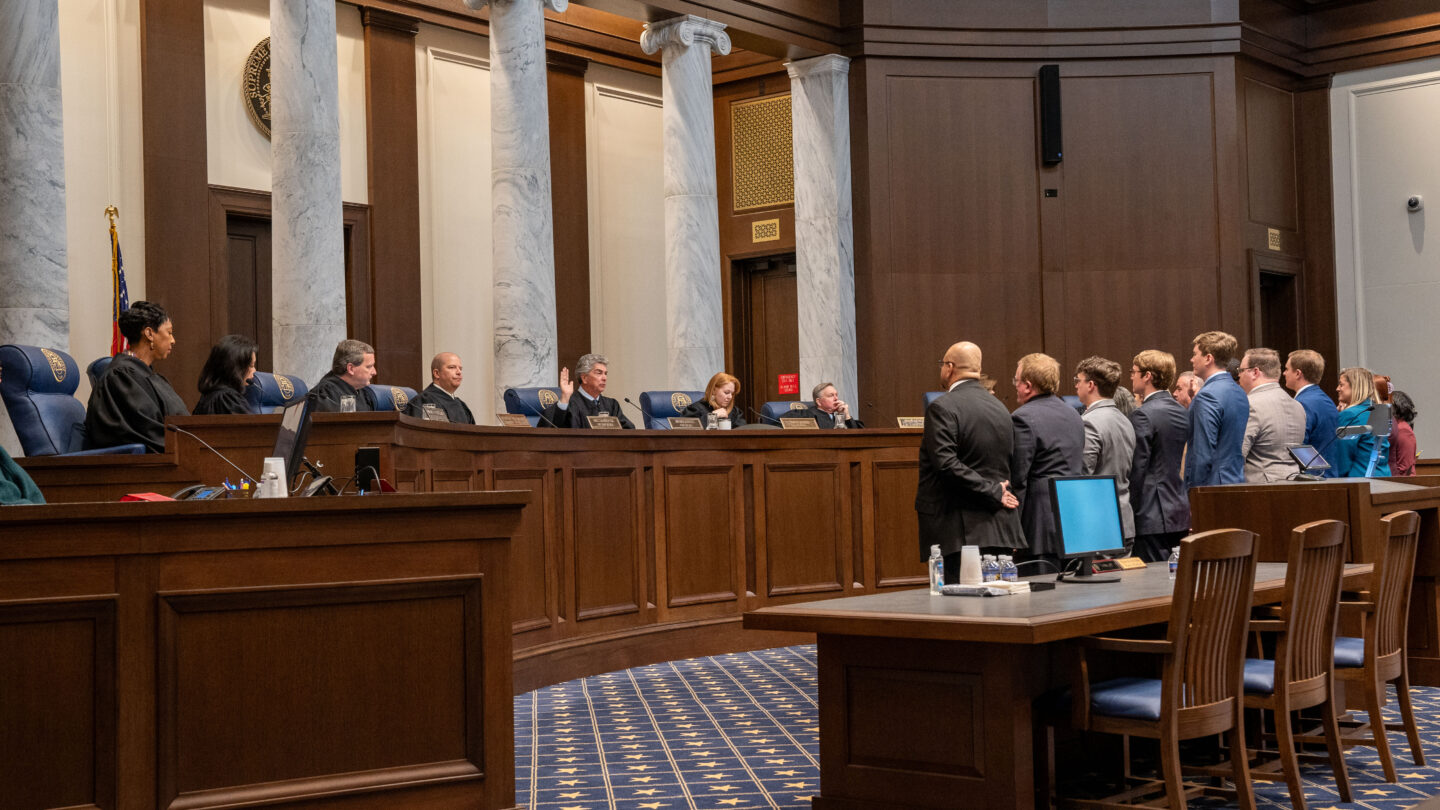

The justices and their role

The Georgia Supreme Court is made up of nine justices who serve staggered six-year terms. New justices are almost always appointed by the governor to fill a vacancy. They face elections at the end of each term, but incumbents historically have always been re-elected.

When justices leave the Court, they typically step down in the middle of their term to make way for an appointment rather than have an open election. Despite having no term limits, there’s a relatively high turnover rate. It’s likely that the makeup of the Court will be completely different 10 years from now.

The current iteration is made of five men and four women, and two people of color. Though nonpartisan, all but one were appointed by Republican governors.

The cases justices consider

The justices issue opinions on as many as 300 to 400 cases each year during three annual terms that last about three months each. Georgia’s Supreme Court differs from other state supreme courts with its rule that cases must be decided within two terms.

As the highest court in the state, it operates similarly to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Georgia court is concerned with state-level appeals and the Georgia constitution, while the SCOTUS is concerned with federal-level appeals and the U.S. Constitution.

But unlike the SCOTUS, Georgia justices aren’t publicly recognized as liberal or conservative.

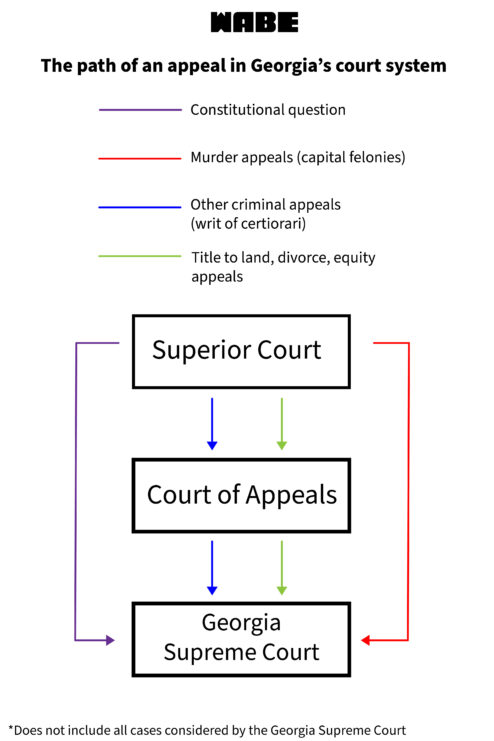

The Georgia Supreme Court has appellate jurisdiction, meaning it has the power to reverse or modify any lower court’s ruling. They do not hear trials, only appeals. The Court has exclusive appellate jurisdiction over some cases, meaning that appeals are considered by the Supreme Court without being heard by the Court of Appeals first.

The following is a list of cases that the Court considers:

- Murder appeals*

- Questions of constitutionality*

- Election contests*

- Writ of certiorari from the Court of Appeals

- Habeus corpus (unlawful detention)

- Extraordinary remedies (extraordinary means to achieve justice)

*Exclusive appellate jurisdiction

Appeals involve a legal or trial error, and don’t question the defendant’s guilt or innocence.

When a case reaches the Court, attorneys submit written briefs stating their grounds for appeal. One justice is assigned to write an opinion and the others review it. The opinion is either adopted, or redrafted and reconsidered until a majority reaches a decision.

Oral arguments occur for writ of certiorari cases, i.e. civil disputes and occasionally non-capital criminal conviction appeals. These cases have errors significant enough to affect state law or affect a lot of people.

The Court has exclusive appellate jurisdiction over questions of the constitutionality of state or local laws.

This happened last year when the Court upheld Georgia’s six-week abortion ban. Advocates supporting a broad lawsuit against the ban argued that the ban was unconstitutional because it was passed before Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022. They argued that the state legislature should have to pass the law again. The Court disagreed and said the law did not violate the Constitution.

On rare occasions, the U.S. Supreme Court will review a decision made by the state court if it potentially violates the U.S. Constitution.

In February the U.S. Supreme Court overruled a decision by the Georgia Supreme Court that would have made an acquitted defendant face a second trial.

A nonpartisan court

Like most state supreme courts, the justices on the Georgia Supreme Court are nonpartisan.

Former Georgia Chief Justice Leah Ward Sears reflected on the partisanship of the U.S. Supreme Court. She said that justices being recognized as liberal or conservative is a relatively new phenomenon. She said that politics seeping in is why so many Americans lack confidence in the SCOTUS.

“Now it’s all about abortion,” Sears said. “There are people trying to find out how you feel about abortion, immigration, all these sorts of issues that are basically legislative issues. Judges … we don’t represent people. We represent the law.”

Fred Smith, an Emory law professor who has clerked for judges, said that Georgia justices avoid nasty campaign battles that are typical of partisan elections in other states.

He echoed what Sears said, saying that voters end up focusing on high-profile cases that judges don’t hear on a regular basis.

“I am in the camp of being appreciative that the Georgia Supreme Court over the decades does not have elections that look like the Alabama Supreme Court or the Wisconsin Supreme Court or the Illinois Supreme Court,” Smith said.

He also said that partisan elections move a lot of action to the primary, which he calls a sorting mechanism for extremes.

“But in the judicial branch, I don’t think that’s a place for extremes,” he said.

Smith added that maintaining the integrity of the judiciary is considered more important than partisan disputes. Often, Republicans will support liberal-coded justices and vice versa.

Appointments over elections

The Georgia Supreme Court relies on governor appointments rather than elections to bring in new justices.

“[In] Georgia’s legal community, it’s more important to them that they have a high-quality court that will listen thoughtfully to arguments and issue opinions in a predictable and principled way,” Smith said.

“Judges … we don’t represent people. We represent the law.”

Former Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Leah Ward Sears

Given the emphasis on appointments, the governor wields a lot of power. Smith said that as political parties have become more ideologically homogenous, it’s become easier for the governor to appoint justices that align with their political views.

On Georgia’s court, all but one were appointed by Republican governors. Justice John Ellington ran unopposed for an open seat in 2018.

Given the coordinated effort in the justice system to avoid electing new justices, it’s nearly impossible for new candidates to get elected. Never in Georgia’s history has a challenger beat an incumbent in an election, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

This year, former U.S. Rep. John Barrow is running against Justice Andrew Pinson. Barrow is campaigning largely on abortion rights, trying to appeal to liberal voters. Barrow has been trying to get elected to the Court since 2019.