How Georgia’s Newspapers Reported 1918’s Solar Eclipse

The total solar eclipse is observed above the mountainous Siberian Altai region,_ about 3,000 kilometers (1,850 miles) east of Moscow, on Friday, Aug. 1, 2008. (AP Photo/Oleg Romanov)

In a week, Georgians will be witnessing what many are calling the “Great American Eclipse.” On Aug. 21, a solar eclipse will pass through the continental United States and soar through the northeast tip of Georgia. Atlanta and metro Atlanta will be able to see at least 90 to 95 percent of a partial eclipse.

It will be a memorable and awe-inspiring event, but it’s not the first time such a large solar eclipse has swept through our continent. About a century ago, everyone was excited about another “Great American Eclipse.”

According to NASA, the totality of a 1918 eclipse passed through the entire continental United States. It started in the Pacific Ocean and climbed into the southern tip of Washington, then it swept straight through the continent and ended in Florida.

Georgia may not have been in the path of the whole eclipse, but the event was still covered by local newspapers both before and after it occurred.

WABE was curious about how newspapers reported on this historic event, and with the resources available in the Digital Library of Georgia, we’ve dug up some interesting articles from that year.

The early 1900s was a different a time, and journalism has dramatically changed since then. We take this information we found in these old articles with a grain of salt and a little light-hearted humor.

Here are six snippets that stood out from 1918’s newspapers.

Newspapers warned that the chickens would roost.

On June 7, 1918, the Athens Daily Herald and the Athens Banner said that the darkness would cause the chickens to roost during the peak of the solar eclipse. Watch out for chickens roosting this year!

Biblical influences were evident.

Today, the South is sometimes called the Bible Belt. That nickname is a result of deeply rooted Biblical influences that were still evident even in 1918.

“There is a total eclipse of the sun scheduled for the 8th of June,” read The Butler Herald on June 6, 1918. “Now this is not the result of an error in the calculations of the astronomers, nor is it due to an order by a modern Joshua, that the sun stand still.”

According to the Bible, Joshua was a leader God appointed to guide the formerly enslaved Israelites to the land that God had promised them.

In the tenth chapter of the biblical book of Joshua, the Israelites are in battle with their enemies. Joshua secures victory for his people by commanding the sun and moon to stand still for the entire day, which confused their enemies.

Christopher Columbus was remembered.

“In the days of the discovery of America a knowledge of astronomy was possessed by very few and many learned in the movements of the sun and moon were looked upon as sorcerers,” read the Athens Daily Herald June 7, 1918. “Columbus knew astronomy and used it to [his] advantage at one time.”

The author tells a tale where Columbus once “predicted” an eclipse to save his life from the hands of native inhabitants of Hayti. When the eclipse took place, they feared Columbus and revered him as a god.

History.com has documented this story but specifies that it was a lunar eclipse — which is not the same as a solar eclipse — that saved Columbus’s life when he was stranded in Jamaica.

“Now when the chickens begin to roost tomorrow about 5:30 don’t worry but think of Columbus and treasure up the memory of the eclipse until the next one arrives 18 years hence,” the author concluded.

Science was tricky.

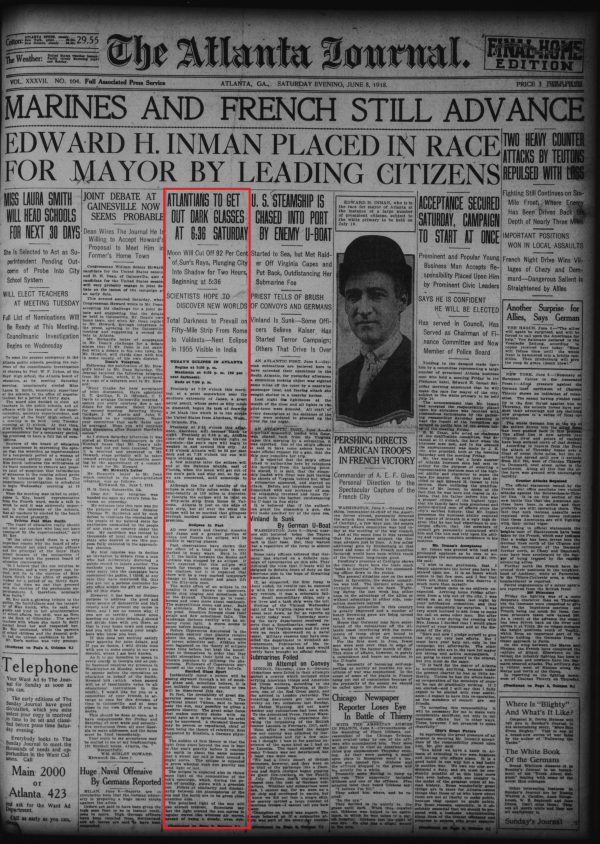

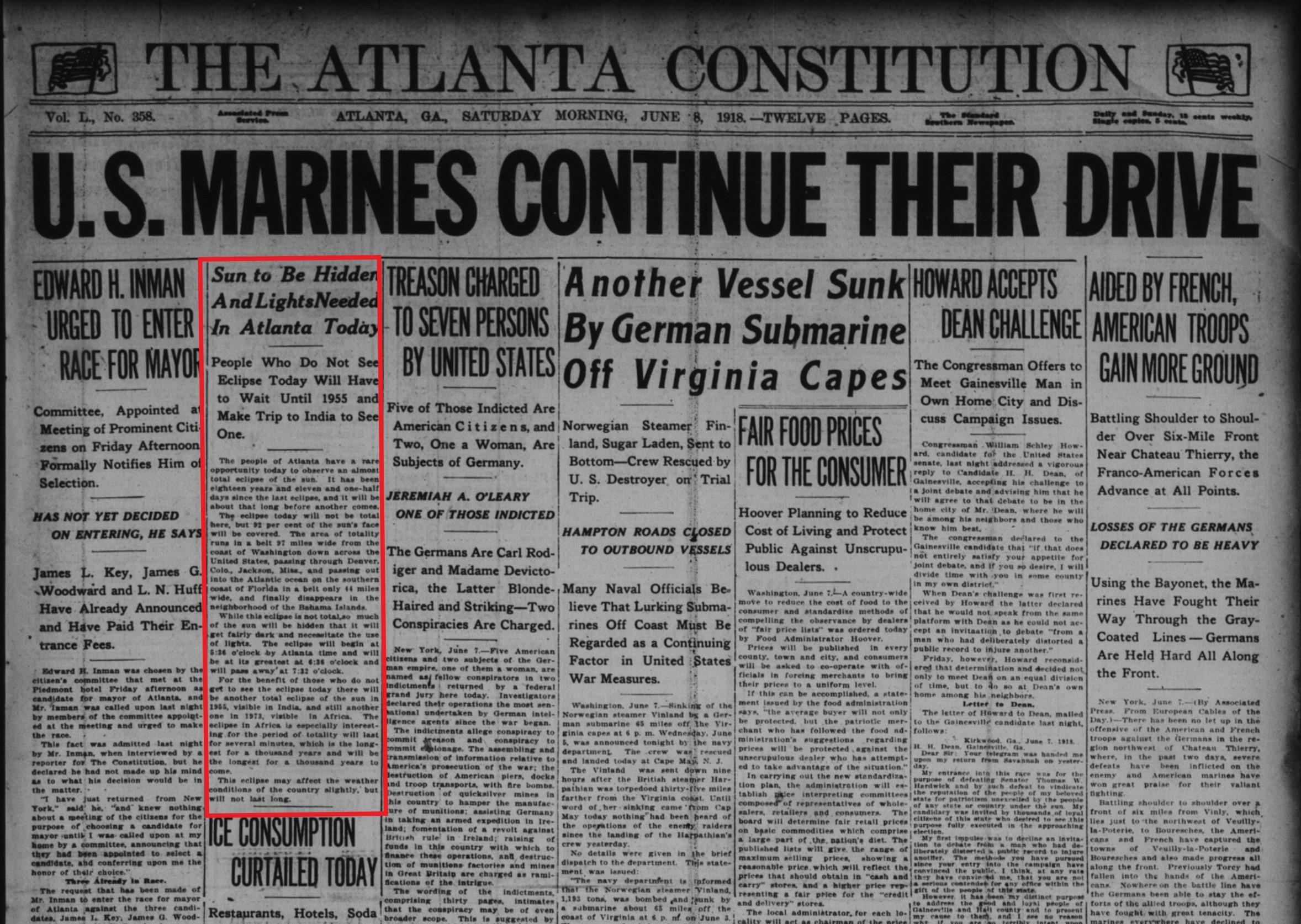

In 1918, some newspapers attempted to predict the times that the eclipse would pass through Atlanta.

Three months before the eclipse, the Athens Banner predicted the time the eclipse was to begin, up to the second. Around the same time, the Weekly Banner tried the same thing.

Both publications reported:

- The eclipse begins at 4:35:38 p.m.

- The eclipse peaks at 5:35:50 p.m.

- The eclipse ends at 6:32:00 p.m.

However, the science wasn’t perfect. Later on June 7 — the day before the eclipse — the Madisonian reported completely different times, which are similar to the times the Athens Banner also published that day.

The article reports:

- Ninety-two percent of the sun would be visible in Atlanta during the peak of the eclipse, and Madison, Georgia, is about in the same path of the eclipse as Atlanta.

- The eclipse would begin at 5:36 p.m. and end at 7:32 p.m.

- Peak darkness is at 6:36 p.m.

- The moon’s shadow would move at 35 miles per minute, passing 330 miles from Rome, Georgia to Valdosta, Georgia in just five minutes.

NASA says that the 1918 solar eclipse actually began at 6:35 p.m., peaked at 7:36 p.m. and ended at 9:31 p.m. in Atlanta.

Mediocre sketchers were called upon for help.

On May 31, 1918, the Athens Daily Herald ran an article written by David Todd, a professor of astronomy at Amherst College.

In his article, Todd enlisted the help of those who have “moderate skill in sketching,” asking them to sketch the eclipse because it would help astronomers study the corona.

“If a field glass, spy glass or telescope of moderate size is available, the best use it can be put into is in outline sketching those parts of the corona near the poles of the sun,” Todd wrote.

Smoked glasses were in style.

Back in 1918, newspapers like the Union Recorder, the Madisonian and The Butler Herald told people to enjoy the eclipse while wearing their smoked glasses.

Today, newspapers are advising the same.

Despite Todd’s ad for sketching help, you shouldn’t try looking at the eclipse through a telescope or a plain, unfiltered glass.

Today NASA warns us not to look directly at the eclipse unless you are wearing special purpose solar filters, commonly known as eclipse glasses. Various science centers and universities in Georgia that are hosting eclipse viewing parties this year and giving out free eclipse glasses to guests and will be using filtered telescopes for safe viewing.

Enjoy the Great American Eclipse Aug. 21 this year, but keep your eyes safe.

WABE’s Al Such, Athens Historic Newspapers Archive, Georgia Historic Newspapers and Milledgeville Historic Newspapers contributed to this article.