The lingering harms of racist lending policies known as redlining are apparent today. Researchers created a set of interactive maps allowing you to explore the current impacts in your city.

Torey Edmonds has lived in the same house in an African-American neighborhood of the East End of Richmond, Va., for all of her 61 years. When she was a little girl, she says her neighborhood was a place of tidy homes with rose bushes and fruit trees, and residents had ready access to shops like beauty salons, movie theaters and several grocery stores.

But as she grew up, she says, the neighborhood went downhill. By the 1970s, stores had disappeared; those that did return were corner shops selling cheap alcohol but “no real food,” Edmonds says. Houses declined too, as homeowners – including her parents – were rejected for loans.

“If the bank’s not loaning, she says, “then things deteriorate.”

Today, Edmonds’ neighborhood remains overwhelmingly African-American, with a poverty rate of nearly 60%. Many of her neighbors suffer chronic medical conditions like kidney disease and diabetes.

“They age differently,” says Edmonds, who works for Virginia Commonwealth University promoting community health. “We have a lot of our neighbors that have health challenges.”

But it’s not just Edmonds’ neighborhood. In city after city across the U.S., from Milwaukee to Miami, researchers have found a disturbing pattern: People who live in neighborhoods that were once subjected to a discriminatory lending practice called redlining are today more likely to experience shorter life spans – sometimes, as much as 20 or 30 years shorter than other neighborhoods in the same city.

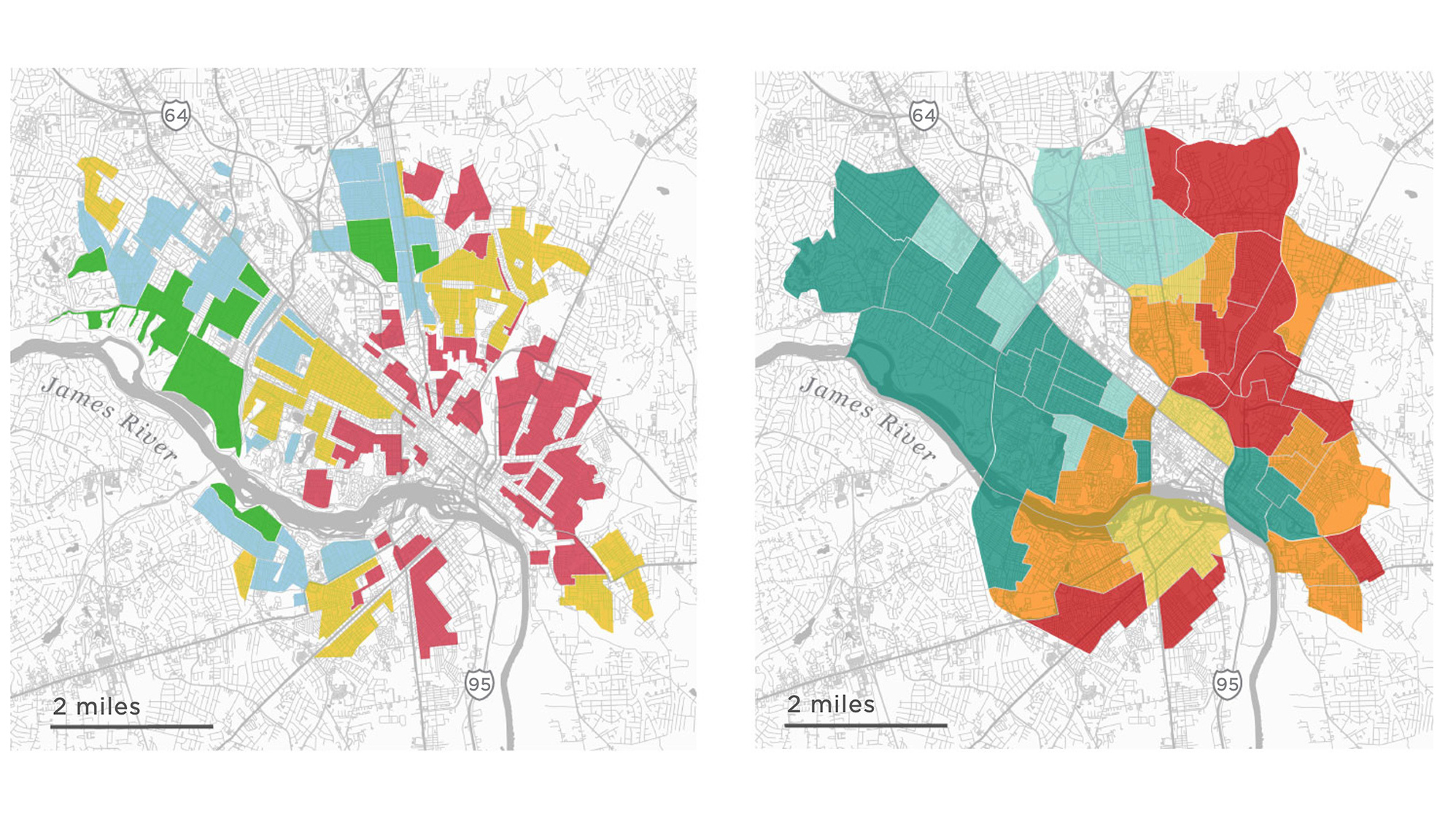

Researchers from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, the University of Richmond and the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee analyzed historic redlining maps from 142 urban areas across the U.S. — these maps, created in the 1930s, classified Black and immigrant communities as risky places to make home loans. They compared the maps to the current economic status and health outcomes in those neighborhoods today and found higher rates of poverty, shorter life spans and higher rates of chronic diseases including asthma, diabetes, hypertension, obesity and kidney disease.

These once-redlined neighborhoods are also more likely to have greater social vulnerability, meaning they’re less able to withstand natural and human disasters because of their more limited resources.

The researchers published interactive versions of these city-by-city maps online for the public to explore their own communities. If your neighborhood was mapped back in the 1930s, these graphics allow you to see how it ranked back then and how it fares today.

What makes these findings especially urgent today, the researchers note, is that these neighborhoods have higher levels of many conditions that raise the risk of severe COVID-19.

“That’s a startling revelation, that this global pandemic is going to have a more serious impact on communities that were redlined by official policy in the 1930s,” says Jason Richardson, research director for the NCRC and a co-author of the study.

Redlining: Federally sanctioned discrimination

The redlining maps originated in the aftermath of the Great Depression, when the federal government set out to evaluate the riskiness of mortgages in major metropolitan areas of the country. The maps, created by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, color-coded neighborhoods by credit worthiness. Areas with African-Americans and immigrants were almost always considered the highest risk, and they were marked in red on maps… hence, “redlining.”

That practice and other discriminatory housing policies of the time helped concentrate poverty in communities of color for generations.

“When banks and other actors are discouraged from lending in the community, you see a very kind of predictable arc of that community,” Richardson says. “When I stop and think about it, I’m kind of shocked by the lingering impact of these policies.”

Redlining made it difficult, if not impossible, to buy or refinance. A lack of investment meant houses fell into disrepair. That led to health hazards like mold and lead paint. Industrial sites were more likely to be located near redlined neighborhoods, which meant more exposure to pollution.

As areas declined, retailers left, including grocery stores, which meant less access to healthy food. These neighborhoods also had less access to parks and other green spaces, meaning fewer places to exercise. All of those factors combined to create an environment conducive to poorer health outcomes, the researchers say.

“Where we live impacts our exposure to health-promoting resources and opportunities,”says Helen Meier, an epidemiologist at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and co-author of the study. “Redlining has systematically shaped characteristics of the built environment in neighborhoods [in ways] that are impacting our health.”

The findings come as no surprise to Edmonds. “Trust me, I know,” she says.

The average life expectancy in her neighborhood is just 68 years. That’s 21 years less than in a well-off predominantly white community a few miles away in the West End of Richmond — a community that got the highest rating on those government redlining maps back in the 1930s. At one point in the pandemic, Edmonds’ zip code — 23223 — also had the highest number of COVID-19 cases in Richmond.

Dr. Lisa Cooper, a health disparities researcher at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, was not involved in the research. She says that people often think of health as the result of individual choices. But she says the redlining study’s findings show how health is also a result of a lack of choices baked into the very fabric of American cities by racist policies made long ago.

“If you just happened to be born in that neighborhood, who’s to say you wouldn’t be in the same predicament?” Cooper says.

Cooper notes that there’s a large body of research linking residential segregation to negative health effects. It’s less about who your neighbors are than about the concentration of disadvantage.”

Structural racism, illustrated

Redlining played a major role in shaping the demographics of modern American urban areas, says Robert Nelson, a historian at the University of Richmond who focuses on urban housing policy and race. And the racism underlying those redlining decisions is undeniable, he says. He’s a co-author of the study on redlining and modern health outcomes.

As director of the Digital Scholarship Lab at the university, Nelson helped create an interactive project that visualizes the study’s findings; it juxtaposes the comments made by federal surveyors who rated neighborhoods on those 1930s maps with their modern-day health indicators. “Infiltration of negroes” is a common reason cited to explain an area’s rating as high risk.

“These are not just racist attitudes. This is policy that is being made by the federal government in these documents,” Nelson says. He says redlining didn’t create residential segregation but helped cement it, because the practice was a federal policy that set a standard which private lenders followed.

“If you want an example of what systemic or structural racism looks like, you really aren’t going to find a better example” than these maps, he says.

Along with other federal segregationist housing policies of the time, redlining helped turn white families into homeowners and moved them into the suburbs, while leaving out many families of color, particularly African-American families, many of whom later ended up pushed into urban housing projects, he says.

“This is a way for white families to build intergenerational wealth, and black families are just cut off from those opportunities for generations,” says Nelson. Although redlining was outlawed by the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the damage was already done, he says.

Links between redlining and health

The redlining maps were first digitized in 2016. Since then, several studies have examined the links between redlining and health outcomes today in specific cities or regions of the U.S., says Dr. Nancy Krieger, a professor of social epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. For example, Krieger’s work has found links between redlining and preterm births in New York City and late-stage cancer diagnoses in Massachusetts.

Other work has found that formerly redlined neighborhoods tend to be hotter than non-redlined areas in the same city, with fewer trees, which also impacts health, as NPR has previously reported.

Krieger, who was not involved in the study from NCRC and its partner universities, says its findings are important because they offer the first nationwide look at the links between redlining and a range of public health outcomes. They also emphasize the ways in which racist policies of the past have ongoing ramifications.

“History never really says goodbye,” Krieger says, quoting the Uruguyan writer Eduardo Galeano. “History says, see you later.”

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))