Judge upholds Georgia's newly-revised political maps

A federal judge has approved Georgia’s newly-revised political maps for Congress and the state legislature, a win for Republicans who sought to preserve their partisan advantage while adding new majority-Black districts required by the court.

“The Court finds that the General Assembly fully complied with this Court’s order,” U.S. District Judge Steve Jones wrote in a Thursday ruling.

The court’s decision to approve the new Republican-drawn maps comes over the objections of the civil rights and religious groups who first sued over Georgia’s maps. They argued that the revised district lines continue to illegally dilute the power of Black voters in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

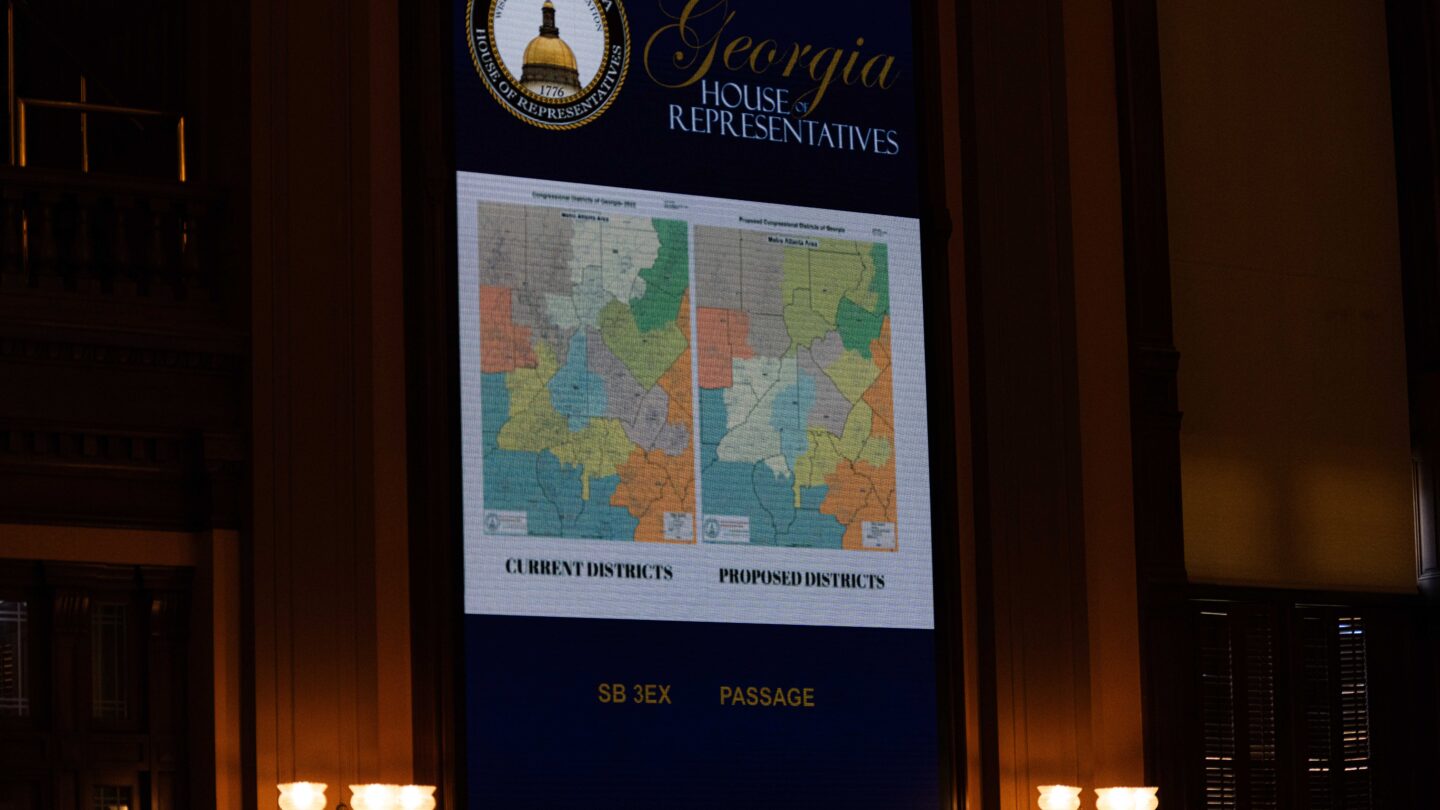

The new Congressional map creates a new majority-Black Congressional district on the west side of Metro Atlanta, but in exchange, dismantles Congressional District 7, a Democratic-voting district on the other side of the city that was not majority-Black, but where Black, Asian American and Latino voters comprise a majority. That will almost certainly allow Georgia Republicans to maintain their 9-5 advantage in Congress.

Rep. Lucy McBath, a Democrat who now represents Congressional District 7, announced Thursday that she will run instead in the new majority-Black district, the new Congressional District 6.

“I hope that the judicial system will not allow the state legislature to suppress the will of Georgia voters,” she wrote in a statement. “However, if the maps passed by the state legislature stand for the 2024 election cycle, I will be running for re-election to Congress in GA-06 because too much is at stake to stand down.”

When Jones, an appointee of former President Barack Obama, ordered additional majority-Black districts in Georgia, he warned the lawmakers against eliminating “minority opportunity” districts elsewhere. But in Thursday’s ruling, he said he was referring specifically to Black voters.

“This Court has made no finding that Black voters in Georgia politically join with another minority group or groups and that white voters vote as a bloc to defeat the candidate of choice of that minority coalition,” Jones wrote.

The plaintiffs argued that these majority-minority, coalition districts are also protected by the Voting Rights Act. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit, which includes Georgia, has said that they are. The U.S. Supreme Court has never weighed in.

Ultimately, Jones decided this was a question for another case, saying the lawsuit until now has only considered Black voters.

“This is the type of challenge to a remedial districting plan that demands development of significant new evidence and therefore is more appropriately addressed in a separate proceeding,” he wrote.

At a court hearing earlier this month, the plaintiffs called on the judge to appoint a special master to draw the maps instead.

Abha Khanna, a lawyer for the plaintiffs, accused the state of playing “whack-a-mole,” substituting one Voting Rights Act violation for another.

“We have seen this movie before,” she told the judge, arguing that efforts by states to find novel ways to skirt the Voting Rights Act have been “par for the course since 1965.”

But Bryan Tyson, counsel for the state, pushed back.

“The state has fulfilled its responsibilities,” he told the judge.

Ultimately, Jones agreed.

He found that the state was not confined to making changes only within the vote dilution area identified by the court. And he ruled that Republican lawmakers did draw the required majority-Black districts in the general areas where the court found that Black voting power had been diluted.

Jones also dismissed plaintiffs’ “invitation to compare” the new maps drawn by the Republican-led legislature and “crown the illustrative plans” proposed by the plaintiffs “the winners.”

The final legislative maps add two majority-Black state Senate districts, but are crafted so Republicans will likely keep their margin unchanged. The state House maps add five majority-Black districts and will likely net Democrats two seats.

“When I am given a task to complete, I do it,” wrote Republican State Sen. Shelly Echols, who chairs the Senate Reapportionment and Redistricting Committee. “Judge Jones told the legislature what he wanted us to do, and we did it.”

Democrats have sharply criticized the maps — accusing Republicans of maneuvering to hold onto their partisan advantage even as the state becomes more competitive.

“The Republican maps discriminate against Black voters and do not allow those voters to elect candidates of their choice,” Senate Minority Leader Gloria Butler wrote in a statement. “We must end the cycle of partisan gerrymandering that allows politicians to choose their voters and prevents voters from choosing their representatives.”

The decision comes on the heels of several redistricting challenges around the country that could shape which party controls the next Congress and the future of the Voting Rights Act.

This is the first redistricting cycle where states with a history of racial discrimination in voting have not had their new political maps subject to pre-clearance from the U.S. Department of Justice.

Earlier this year, the courts upheld rulings requiring Alabama to redraw a new Congressional map to remedy violations of the Voting Rights Act. The court eventually appointed a special master to draw the map — a decision ultimately upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In Georgia, the plaintiffs may appeal the ruling, but the maps must be finalized by Jan. 29, when election officials begin the process of creating ballots for the 2024 elections in the spring.