Pandemic Restrictions Leave Much Unknown In Long-Term Care Facilities

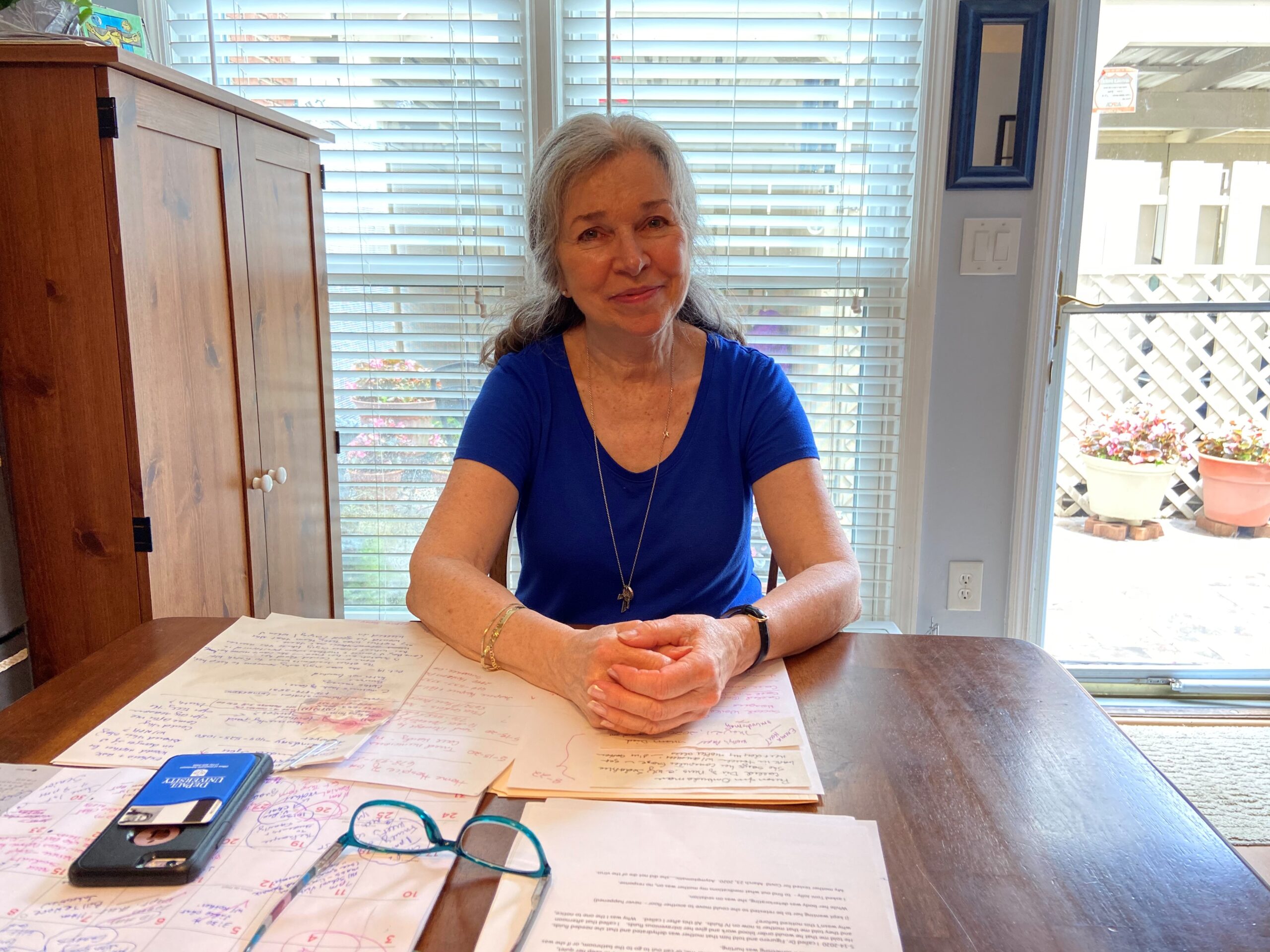

Michele Berrell is considering her legal options and has filed a complaint with the state about her mother’s treatment at a Union City long term care facillity. “With this COVID thing…it’s like you gave over complete control,” she said.

Emma Hurt / WABE

Just under half of all coronavirus deaths in Georgia have been in long-term care facilities, like nursing homes and personal care homes. In an effort to protect some of the most vulnerable people in the state to the virus—the elderly—the state barred most visitors to these facilities.

State regulators are only permitted inside facilities for certain complaints, including those of immediate danger to a resident or related to infection control. Advocates are also no longer permitted inside, including long-term care ombudsmen.

Melanie McNeill, Georgia’s state long-term care ombudsmen, and her colleagues are government-funded to advocate for families and residents in long-term care facilities.

“In normal times, our ombudsmen representatives visit with residents of facilities at least quarterly,” McNeill said. “They’d go in the building, so they’d make observations. How does it look? How does it smell? How do the residents look?”

And sometimes, things go wrong, even for facilities ordinarily without problems, she said. There’s always a worry about what they aren’t seeing on their visits.

“But now, with nobody else in the building, it’s exacerbated,” she said. “Our worry is so much higher because we can’t tell.”

‘You Gave Over Complete Control’

Michele Berrell’s mother, Paulette Burnette, moved into a Union City assisted living facility, Christian City, in 2016. But soon enough, she said she started to notice issues. “Things began to go wrong. Mistreatment, food under her fingernails,” she said. Berrell recalled finding her mother with dirty hair and teeth and in the wrong clothes.

She filed complaints and said the facility promised things would be better. But during the coronavirus pandemic, when Berrell was barred from seeing her mother, things got worse.

“With this COVID thing and not being able to see her, it’s like you gave over complete control,” Berrell said.

She was able to see her mother through videoconferencing, but those appointments were unreliable and would sometimes be canceled or postponed by staff.

Ombudsmen are largely relying on telephones to talk to residents, McNeill explained, which can also be unreliable. Sometimes phones aren’t charged or are in use, and sometimes it just isn’t possible to communicate with residents.

“Sometimes, you can understand a person when you see them in person, but you can’t really understand them very well over the phone,” she said. “You can’t see the body language. You can’t see the facial expression.”

It makes the advocates’ job even more difficult and generates fear, McNeill said. “Fear that we’re all feeling, I think, that people we know may suddenly come down with this, and there isn’t a way for us to really know that for a resident because we can’t really see them or talk to them.”

The Department of Community Health has documented more than 6,500 coronavirus-positive long-term care residents in Georgia and nearly 1,200 deaths. Those numbers do not include more than 9,700 beds in the state’s smaller personal care homes, which are not being tracked.

In an effort to zero in on long-term care facilities’ safety, Gov. Brian Kemp activated the state National Guard to travel the state disinfecting locations. They’ve visited more than 2,000.

“We’re dealing with nursing homes every hour of every day,” Kemp said. “And I think everybody else around the country is as well. We’ve taken extraordinary measures in the state.”

“We’re grateful that the governor had this idea to send the National Guard in. I think it’s really helpful,” said McNeill.

‘A Lot of Systematic Problems’

Lori Smetanka is executive director of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, a national organization that advocates for long-term care residents. She’s been hearing about this situation around the country.

“Staff are doing heroic jobs in terms of caring for people right now. We really want to acknowledge that. We recognize that,” she said.

“But this industry has a lot of systemic problems that are not going away because we’re in a pandemic.”

Those problems include staff shortages and low pay, lack of oversight for regulatory standards and lack of accountability for public dollars received.

The situation in the pandemic “really leaves the residents without a lot of support for help when they need it,” she said.

One big concern is about the people they’re not hearing from, she said, particularly residents who have trouble communicating.

“We’re getting one level of perspective about what’s going on in those facilities,” she said. “It’s been very difficult for families and ombudsmen to communicate with those people who have the greatest needs either because of their medical or cognitive disabilities.”

With this COVID thing and not being able to see her, it’s like you gave over complete control.

Michele Berrell, whose mother, Paulette Burnette, moved into a Union City assisted living facility, Christian City, in 2016

Michele Berrell’s mother, Burnette, fell into that category during the pandemic.

Berrell noticed Burnette had dramatically slipped downhill over their video chats. She was mumbling and barely talking, so Berrell received special permission to come visit with protective gear.

In person, Berrell said, Burnette seemed “almost comatose.” In person, Berrell was able to ask a nurse about it:

“Just very matter of factly talking, [the nurse] says, ‘Oh yes, we sedated your mom because she was calling out. She was calling for you,’” Berrell said.

In person, she also noticed that her mother seemed dehydrated and advocated to get her IV fluids.

Christian City’s parent company, PruittHealth, did not respond to the specifics of Berrell’s allegations. In a statement, a spokeswoman said “the health and safety of our patients and staff are top priorities.”

One day in late May, Berrell said, a scheduled video chat with her mother was postponed by staff.

The next day she called to check on her mom and was told in the morning she was doing well.

“That afternoon, 4:36 p.m., she’s dead. She’s dead, and nobody was with her,” Berrell said. “And I thought, ‘How do you know the exact time if nobody was with her?’”

Berrell has filed a complaint with the state and is considering her legal options.

PruittHealth’s spokeswoman said the company is “saddened” by the loss and asked for prayers during this “difficult time.”

The state’s ban on long-term care facility visitation is currently through June 30.