Learning Through Improv: A Local Nonprofit’s Fun Approach To Teach Students With Autism

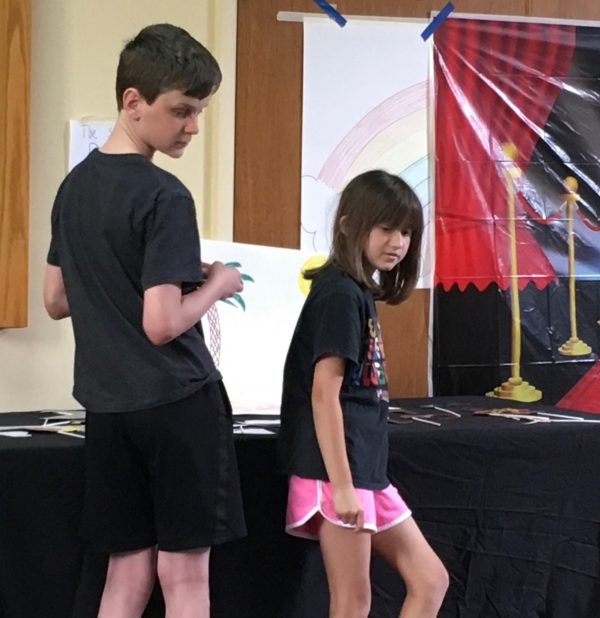

Shenanigans teacher Taylor Kristan improvises a phone conversation with one of her students. Shenanigans is a camp that teaches kids ages 8 to 12 the art of improvisation. The camp serves students on the autism spectrum who need low levels of support. However, the program doesn’t require that kids have an autism diagnosis to participate.

Autism Improvised

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) can affect a person’s social and communication skills and behavior.

“It means that the ways the person sees and processes and uses social information, as well as some of the challenging behaviors and different behaviors the person may have, really kind of add up to say this person needs adaptations, they need extra help in communicating and interacting with the world,” says Catherine Rice, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory University and director of the Emory Autism Center.

People on the autism spectrum often have remarkable talents. They can also struggle with self-expression.

Experts refer to the “spectrum” because people with autism often have different needs, capabilities and challenges. Some on the spectrum need a high level of support, while others need less.

There’s a wide range of therapies available. However, one local nonprofit takes a unique approach to working with people on the spectrum by teaching communication skills through improvisation.

Up To ‘Shenanigans’

On a Thursday morning in June, seven kids gather in a Marietta church for a weeklong summer camp. The camp teaches kids ages 8 to 12 the art of improvisation, where actors make up scenes as they go along.

This camp, called Shenanigans, serves students on the autism spectrum who need low levels of support. However, the program doesn’t require kids to have an autism diagnosis to participate.

The students start with games. The first one is called “Dude.” Everyone in this class of seven students and four adults sits in a circle. They take turns picking an emotion. Then each person in the circle repeats the word “dude” using that emotion. This gets them talking, and soon their teacher Taylor Kristan moves them on to performing scenes with a partner.

Here, students are reminded to remember the classic improv rule, “Always say ‘yes.’” So, if a scene partner says you’re going to the zoo, the other agrees and adds to the idea. He can’t say, “No, we’re going to Mars instead.”

Before going ahead with a scene, Kristan guides the kids through the setup. She asks them to name a relationship between the two scene partners. Then, the class has to come up with a problem for the actors to solve.

Improvisation requires spontaneity and a certain lack of inhibition. That can be hard for kids on the spectrum.

Randy Hain’s son Alex is an adult now, but he attended Shenanigans as a kid. His dad says one feature of Alex’s autism is that he liked to know exactly what’s coming.

“So Alex, going to improv, was like, ‘Dad, what should I do? What should I expect? What’s going to happen?’”

But, his dad says, Alex learned to relax and trust the program. Kids enrolled in this summer’s program seem to be learning to do the same. The program’s student/teacher ratio is 2:1. So, if a child is getting frustrated or needs to take a break, one of the adults can take her aside and let her rejoin when she’s ready.

The students gush about the program.

“I love it,” says 9-year-old Julia D’Anthony. “It’s so fun. I want to come next year and the year after that and the year after that. I love it so much.”

Necessity Is The Mother Of Invention

Shenanigans is run by a nonprofit called Autism Improvised. Sandy Bruce is the group’s founder. She was looking for a theater program for her grandson who is on the autism spectrum.

“When I started researching theater, I came across improv and, lo and behold, everything improv does just dovetailed with all of his challenges that he had,” Bruce says.

She couldn’t find any improv programs for kids with autism. So, she started her own.

The program has grown from serving young children to include teenagers and young adults. It offers programs during the school year in addition to summer camps.

One of those programs, called “Code Breakers,” has partnered with the Excel program at Georgia Tech. Students in this program are between 16 and 22 years old. They play games, too, but theirs are designed to help students adapt to the workplace. They work on recognizing more subtle forms of communication, like picking up on social cues and sarcasm in someone’s voice.

“If you’re missing social skills, if you don’t know how to deal with that person in HR, if you’re unsure how to have a conversation or small-talk conversation, it hinders you greatly,” says Code Breakers teacher Jason Evans. “So we teach these kinds of skills. We role play. We get up, and we try these things.”

They practice thinking on their feet by starting a story that everyone adds to. It starts at a bank and ends with a zombie invasion. They practice interacting with each other through an improv game called, “What Are You Doing?” where students have to make up answers on the spot.

Code Breakers partners with Georgia Tech, in part, to give the students a feel for the campus. They get to think about what it would be like to attend college or become independent. Evans asks the groups to name some fears about going away to school. Responses include making new friends and showing up to places on time.

George Barham, 22, has been coming to Autism Improvised for years and says the classes have made a difference.

“It helped me learn how to apply for jobs,” he says.

He works part-time at Amazon and helps out at this Code Breakers camp.

There’s not a lot of evidence that programs like this have long-term effects. But Catherine Rice, of Emory, says the program has an important element of autism intervention: engagement.

“Your mind, your body, your voice, you are actively engaged and interacting or problem-solving or doing something versus just wandering or spacing out or sitting or passively consuming information, which often happens,” she says. “We particularly see that for adults who don’t have access to education or support programs anymore.”

Christina Seidel’s son Sam attended Shenanigans years ago. He’s an adult now. At the time, Seidel struggled to find the right school for him.

In addition to being on the autism spectrum, he’d been diagnosed with dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. For Seidel, the value of Autism Improvised is less about success rates and more about how Sam felt when he went to class.

“He just was able to be himself and be around other kids that were like him and just be accepted, and that was just a truly amazing gift,” she says.