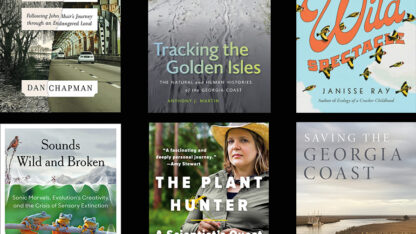

New book explores the South's unique — and threatened — natural beauty

When John Muir encountered the Chattahoochee River shortly after the Civil War, it hadn’t yet been dammed or affected by years of sewage dumping. Now, it’s getting cleaner again.

STEVE HARWOOD / FLICKR.COM/CAPTKODAK

Just after the Civil War, John Muir, who went on to be an influential environmentalist but was at the time a “nobody,” went on a very long walk across the Southeast.

Traveling from Kentucky, across Tennessee and Georgia before hopping on a boat to continue his walk in Florida, Muir documented the flora of the region before it was cut up by highways and tarnished by pollution.

About 150 years later, Atlanta journalist Dan Chapman set out to follow Muir’s trail to find what’s changed.

The answer: pretty much everything.

“It’s really hard now to find — but there are certain places you can find — what it was like when Muir traipsed through there,” Chapman says. “When I found those places, it was magical.”

In Chapman’s new book, “A Road Running Southward,” he explores the natural beauty of the Southeast, the many things that threaten it and the distinctive characters trying to help.

How Muir’s journey through the South shaped his thoughts on environmentalism:

“Throughout his trip here, he just had sort of these epiphanies, these eye-opening moments. And probably the most interesting one is when he spent five or six nights in Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah.

“He was out of money, he was starving. He might have been in the early stages of malaria because he got very sick soon thereafter. But when he was there in the cemetery, where the dead lived, his whole philosophy about life, and man’s relationship to life and nature, crystallized.”

What’s changed in the environment since Muir’s walk:

“Just from sprawl; to coal ash, where, you know, it’s pretty hard to get much worse than what coal ash has done to not only rivers but also communities and peoples; to just how we’ve so abused the Chattahoochee River, the Savannah River, in particular; the beautiful natural springs of North Florida, all these areas that he passed across now are really in bad shape.”

Finding signs of hope:

“I think in certain places, we’ve done a really remarkable job in cleaning some of this stuff up,” he says. “The people who are really trying to make things better are remarkable. And that gives me hope.”

“The region we live in is just incredibly biodiverse. You know, you can go from 6,500-foot mountains down to below sea level on the coast in about five hours. And along the way, you’re just going to have these amazingly different ecosystems. You’ve got the mountains, you’ve got the pine forest, you’ve got the hills and ridges, you’ve got the swamps. It’s all here and we have it in such abundance.”

Navigating Muir’s racism:

“It wasn’t easy,” Chapman says. “As I read his book, it doesn’t take long for him to start dropping nasty words and calling people nasty names and everything. And it just floored me, I stopped and I’m like, ‘Well, you know, holy … this guy was a real cretin.’”

“The book isn’t about him. It’s not a biography about him. But he obviously plays a central role in the book. And it made me think, ‘Well, should I really be shining a light on this guy who I call a racist, and he was a racist.’”