New exhibit, 'And I Must Scream,' looks at the irreversible damage caused by humans

As we look around the world, we see irreversible damage humans have caused – global warming, pollution, colonialism, corruption; the list goes on. What do we do when Pandora’s Box of man-made problems has been opened? This question is explored in a new exhibition of international artists at the Michael C. Carlos Museum on Emory’s campus, “And I Must Scream.” “City Lights” producer Summer Evans spoke with the museum’s curator of African art, Dr. Amanda Hellman, about the exhibit and its journey through the frightening realities and possibilities of humanity’s present and future.

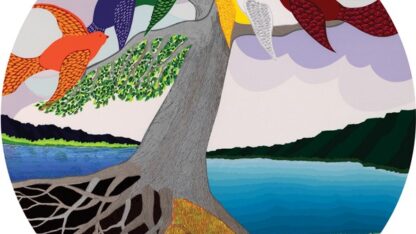

Hellman explained the five themes of “And I Must Scream,” including environmental destruction, human rights violations and governmental corruption, displacement and the COVID-19 pandemic. A final theme addresses regeneration and renewal, exploring how humans can aim to right the wrongs of the past.

“But the point is really not that we look at any of these themes individually, but really, we look at the connections,” said Hellman. “You can’t talk about the pandemic without talking about environmental destruction and displacement…. You can’t talk about environmental destruction without looking at corruption and the ways in which these things are really speaking to each other and connected to each other.”

The exhibition gets its name from a short science-fiction story by Harlan Ellison, “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream,” in which a man-made artificial intelligence destroys all but a few unlucky humans, keeping them alive to be tortured by the otherwise purposeless and amoral computer.

“As I was thinking about all of these different monstrous systems… I wanted to explore, ‘So now what?’ Right? What happens once these monsters are released?” Hellman mused. “Once plastic is created, you can melt it down and reform it into something that looks different. You can turn a plastic bottle into a pair of shoes or a blanket, but it never goes away. And so [I was] thinking about the monster as something that maybe we need to take control over and redirect so that it becomes a monster of renewal and regeneration rather than of destruction.”

Near the exhibition’s entrance hangs “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” a large-scale photographic work named after Francisco Goya’s 1799 print. The photographer, Yinka Shonibare, recreates Goya’s composition with a figure hunched over a desk surrounded by fantastically posed taxidermy owls bats. Its aluminum backing material enhances the photograph’s unreal tones.

One of Hellman’s professed favorites in the exhibition is “Perruche Perruque,” an arresting drawing by Steve Bandoma, an artist from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “The figure is on a white background and is wearing a traditional Western ceremonial military garb. It’s bedazzled in an interesting way where it’s got glitter on the shoulders. But then the head, the center of logic and compassion, is replaced by a parakeet wig, and so you see this bulging eye emerge from this pandemonium of parrots,” said Hellman. The curator also posited a possible connection between the use of brightly-colored scarlet macaws and the colors of the current DRC flag – red, gold and blue.

Other artists featured include Fabrice Monteiro of Benin and Belgium, Thameur Mejri of Tunisia, Anida Yoeu Ali of Cambodia, and more.

More on “And I Must Scream” at the Michael C. Carlos Museum at Emory University, on view through May 15, can be found at https://carlos.emory.edu/exhibition/and-i-must-scream.