Pandemic—Briefly—Interrupts Georgia’s Steady Eviction System

Legal aid attorney Viraj Parmar said the pandemic temporarily gave tenants something they wouldn’t normally have in Georgia’s eviction process: time.

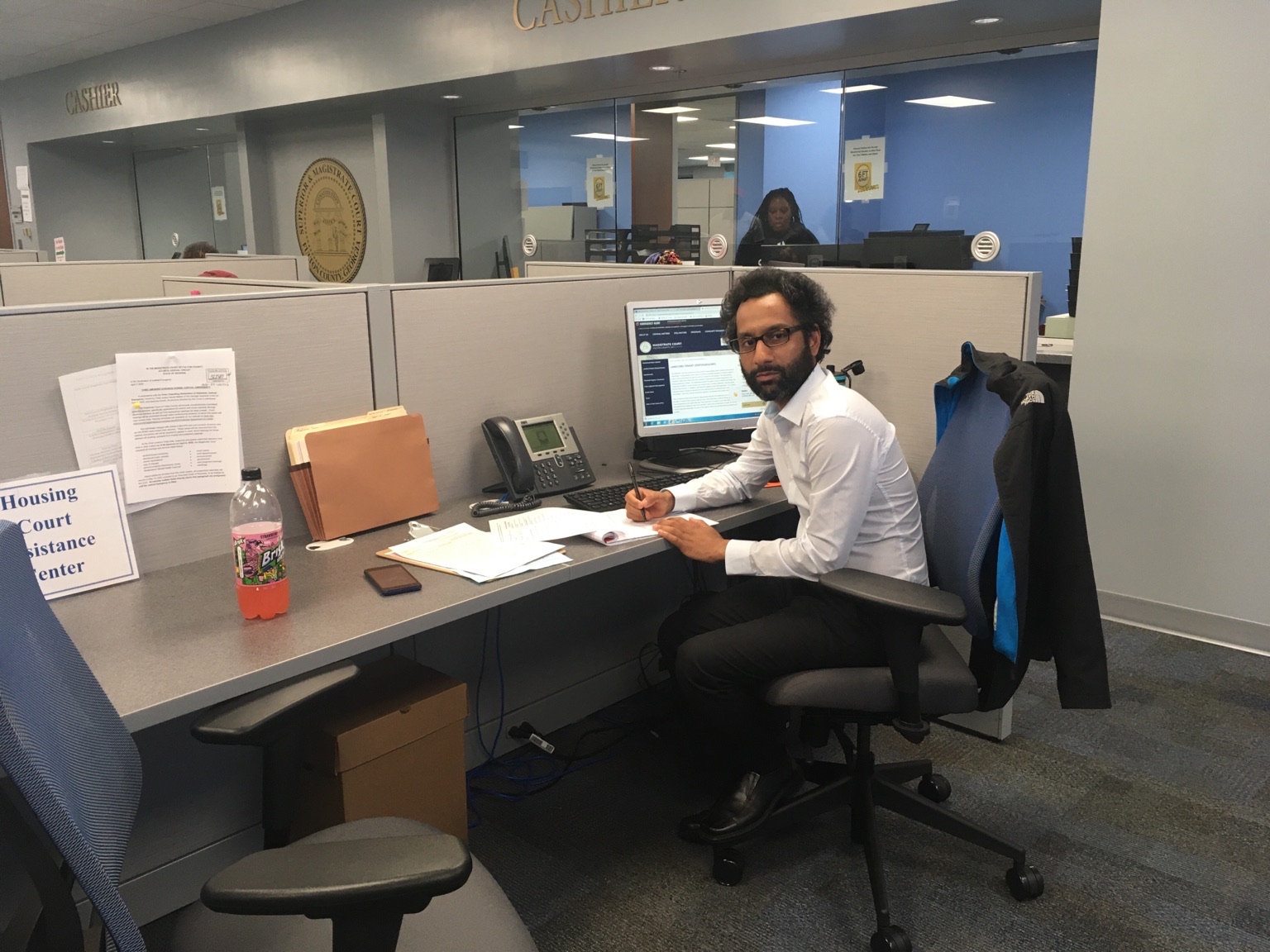

Courtesy of Viraj Parmar

From his cubicle inside the Fulton County Magistrate Court, Viraj Parmar is used to delivering bad news.

“I preface everything with, ‘I wish it wasn’t like this, but this is the way it is,’” he said.

Parmar runs the Housing Court Assistance Center for the Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation. He answers tenants’ questions about legal issues like evictions.

He said they often show up thinking they have more protections than they do.

“They’ve done some Googling, and they’ll find out what the law is in, let’s say, Massachusetts or California,” Parmar said.

Those are places where renters have days, if not weeks, to catch up on late rent and where it can take months before courts ultimately approve their evictions.

Parmer has to break it to the tenants: they live in Georgia.

“The law in Georgia doesn’t require a grace period or anything like that,” he said.

Landlords can file for eviction as soon as tenants are late on rent. And within a few weeks, law enforcement could remove those tenants from their units.

Georgia is a state where the eviction process is usually steady and reliable.

Since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, little has operated as usual, including the Fulton County Courthouse, where Parmar works.

The court that churns out 40,000 eviction rulings annually suspended all hearings in March. Cases have been on hold since.

The hiatus has given Parmar some better news. Tenants have something Georgia law normally wouldn’t allow: time.

“There’s some leverage, and that’s using the time to say, ‘You can’t evict me. You can’t force me out. The courts are closed,’” Parmar said.

With time, he said, tenants have options. They can negotiate payment arrangements with their landlords or simply come up with a better exit plan.

For Yvette, it meant avoiding an even more difficult situation for her family.

“I just felt like we probably were going to be homeless,” she said.

Yvette, who asked not to share her full name, was behind on rent before the pandemic. She had cancer and faced mounting bills.

She wanted to stay in her north Fulton home. She and her daughter lived there for eight years.

“My daughter considers it as the home that she grew up in. She spent the bulk of her childhood here,” she said.

She tried to work out a payment agreement with her landlord but was unsuccessful. Meanwhile, her case continued swiftly through the court.

And soon, she found herself days from being forced out.

“That’s when they started talking about stopping evictions,” she said.

Suddenly, the coronavirus outbreak shut everything down.

The delay gave her a moment of relief. She at least could find a new home–when her family nearly had none.

More time may not seem that significant. But it’s something Professor Megan Hatch at Cleveland State University looks for in her research on eviction laws.

“I’m really interested in anything that extends the process and makes it take longer,” she said.

That could be through the defenses tenants can provide or their ability to appeal.

She said the longer evictions last, the more expensive and difficult they become, usually for the landlord.

The hope from tenant advocates is that may prevent landlords from filing in the first place.

It’s difficult to compare eviction cases by city or state. There is no central database. But in data compiled by the Princeton’s Eviction Lab, Georgia’s eviction filing rate has led the country–double that of New York and four times that of Massachusetts.

According to Hatch, time in the eviction process can set pro-tenant laws apart from laws that are pro-landlord. And in that way, the pandemic could make places like Georgia a little more pro-tenant.

“It’s changing the landlord-tenant relationship, at least temporarily,” she said. “It’ll be interesting to see if we go back to what we were before, or if there’ll be changes in those relationships.”

Those who represent landlords, however, are skeptical that the court shutdown could bring any long-term benefits for tenants.

Attorney Paula Mcgill works with smaller landlords who own just a few properties.

“Oh, they’re frustrated,” she said. “There was one client who had their case dismissed on a technicality. They didn’t understand the law.”

The client came to Mcgill, and she was about to bring the case to court. Then, the virus hit.

“So they’re stuck with a tenant who hasn’t paid rent for five or six months,” she said.

Many landlords will need to make up that lost rent to pay their mortgages, she said. They’ll probably do so by raising rents.

And Mcgill said that will be after they evict their current tenants, which will happen as soon as the courts reopen.

Fulton County is now considering what cases its magistrate court can continue in the next month of the public health crisis. Guidance about evictions is expected by Friday.

Once hearings resume, attorneys like McGill predict the gears of the state’s eviction system will start turning again as steadily and reliably as before.

Parmar, the legal aid attorney, said he recognized that reality. The Atlanta Volunteer Lawyers Foundation plans to expand the housing clinic hours to meet the need.

“It’s gonna be sad,” he said. “It’s going to be en masse evictions where it’s going to be a large group of people trying to find a place to stay.”

This story was produced in part with funding from the Ravitch Fiscal Reporting Program at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY and is part of a nationwide project on how state safety nets are handling the coronavirus economic fallout.