Professor Sara McClintock leads book discussion on 'Divine Stories' at the Carlos Museum

The religion or practice of Buddhism began over 2,500 years ago in India. It has nearly 500 million followers worldwide, including celebrities like Tina Turner, Alice Walker, Jet Lee, k.d. lang and the late David Bowie, to name a few, and continues to grow in the West. The book “Divyavadana,” or “Divine Stories,” draws on the accounts of classical Buddhism in India and offers practical wisdom on how Buddhist teachings can improve everyday life.

On Oct. 24, as part of the “Carlos Reads” program at the Carlos Museum at Emory that offers discussions on the works of literature related to the museum’s collections and exhibitions, Associate Professor in the Department of Religion at Emory Sara McClintock will lead a discussion on the “Divine Stories” literature. McClintock joined “City Lights” producer Jeannine Etter via Zoom to share more about the influence of Buddhism on today’s spiritual seekers.

Interview highlights:

How Professor McClintock became drawn to Buddhism:

“I was, quite frankly, looking for an understanding of the human condition, trying to find out answers to questions like, ‘Why is life so hard, and what can I do to make the world a better place’?” said McClintock. “I became inspired to study religion, something about which I had previously not had knowledge or interest, and I ended up studying at Harvard Divinity School for a master’s degree. While I was there, I studied Buddhism with my teacher, Professor Masatoshi Nagatomi.”

They continued, “I was particularly drawn to this interesting combination of an ethics rooted deeply in compassion and a metaphysics rooted in groundlessness. It sounds a bit of a contradiction and it kind of is, but the idea in Buddhism is that there is only flow. There’s nothing stable to which we can grasp, but that flow and that groundlessness and that emptiness, to use a Buddhist term, also provides a great deal of freedom. And within that space one can cultivate wholesome mind states, including boundless compassion which extends to all the sentient beings of the cosmos.”

Origins of the dharma and divine stories:

“Buddhism begins in India, probably in around the fifth century B.C.E. with this figure who comes to be known as the Buddha, the ‘awakened one,’ and it becomes a pretty successful religious tradition with a large number of Buddhist monastics, men and women who take vows as renouncers and do not have a single stable home,” said McClintock. “They are wandering throughout the continent. They do have some monastic centers, but as they are moving around, they are traditionally begging for their food. This is how they survive, and lay people, those who are not the renouncers, provide provisions for the monastics, and in exchange, the monastics give them teachings — so called ‘dharma’ teachings.”

“When the monks were traveling around, they might go to a pilgrimage site, they might go to a marketplace, they might go to a bazaar, and in these locations, they might set themselves up under a Banyan tree, for example … and they could attract a crowd by telling some of these marvelous stories. Now, what are the stories for? Well, the stories, the divine stories have a focus on karma. A lot of people have heard of the term karma, and there’s a sort of general perception in America these days that karma means, more or less, ‘what goes around comes around…’ but the word ‘karma’ literally means action and it refers to all of the actions that we do in our lives with our bodies, with our speech, and with our mind.”

On the Carlos Museum’s new commissioned works of Buddhist art:

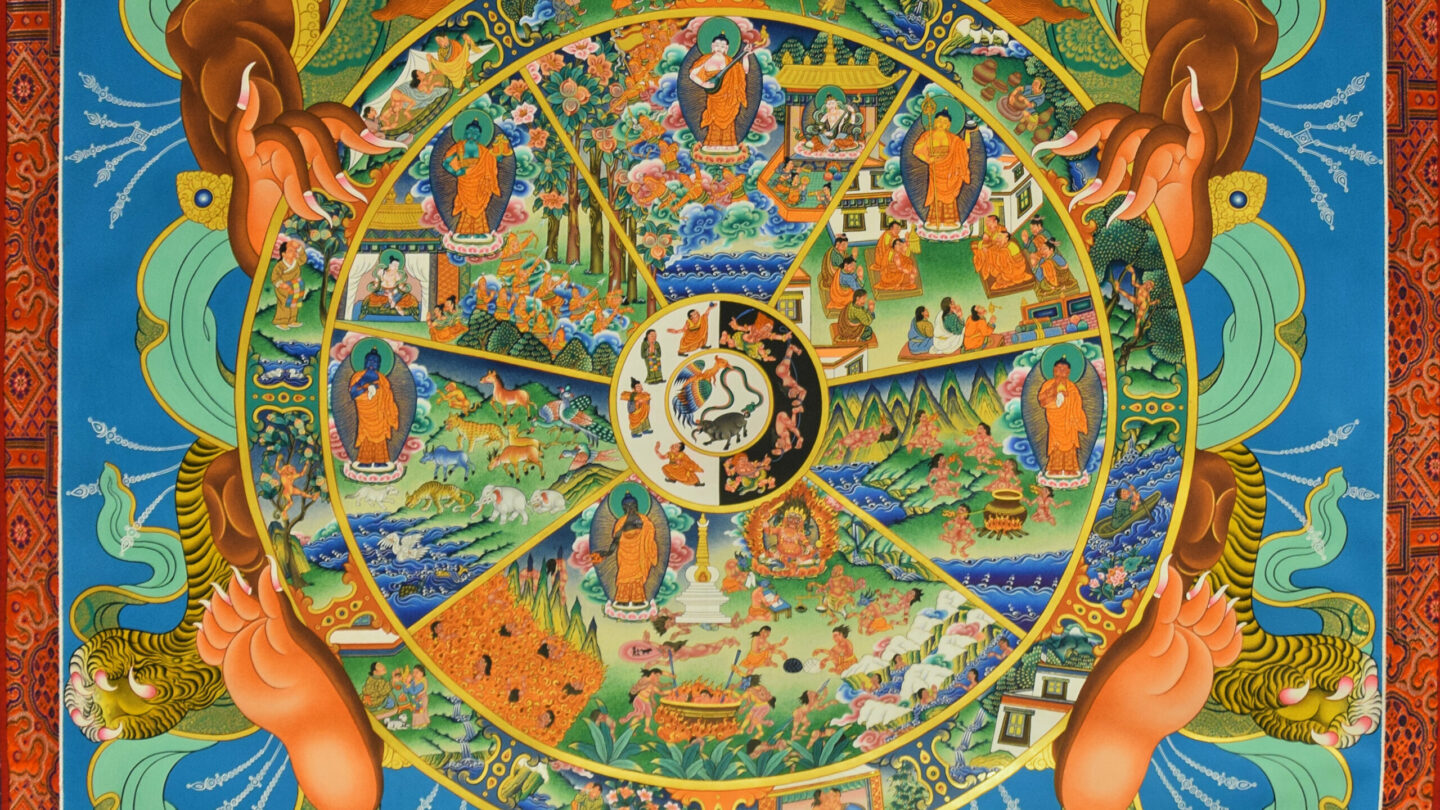

“Last year the Carlos Museum at Emory commissioned two new Tibetan ‘thangka’ paintings. A thangka painting is a scroll painting,” McClintock said. “One of them is illustrating the path to tranquility, which is a certain kind of meditation, ‘shamatha’ meditation, in which one learns how to calm the mind, tame the mind. And that particular painting has an elephant that is being led by a monkey, but eventually the monkey is tamed.”

“The other thangka painting that we’ve acquired, that we commissioned … is called ‘The Wheel of Life,’ or ‘the wheel of existence…’ And the ‘Wheel of Life’ is made up of four concentric circles with different levels of explanation in each of the circles, and the entire thing is held by a monster who really represents time or impermanence. He’s in the form of the Lord of Death, and the idea being that nothing remains the same. Everything is constantly changing and all that comes into being will pass out of being again. But at the same time, there’s a continuation in a new life.”

Sara McClintock will lead a discussion Oct. 24 at the Carlos Museum at Emory University on the “Divine Stories” literature of Buddhism. More information is available here.