Teaching program gives refugee women opportunity to rebuild careers in Atlanta

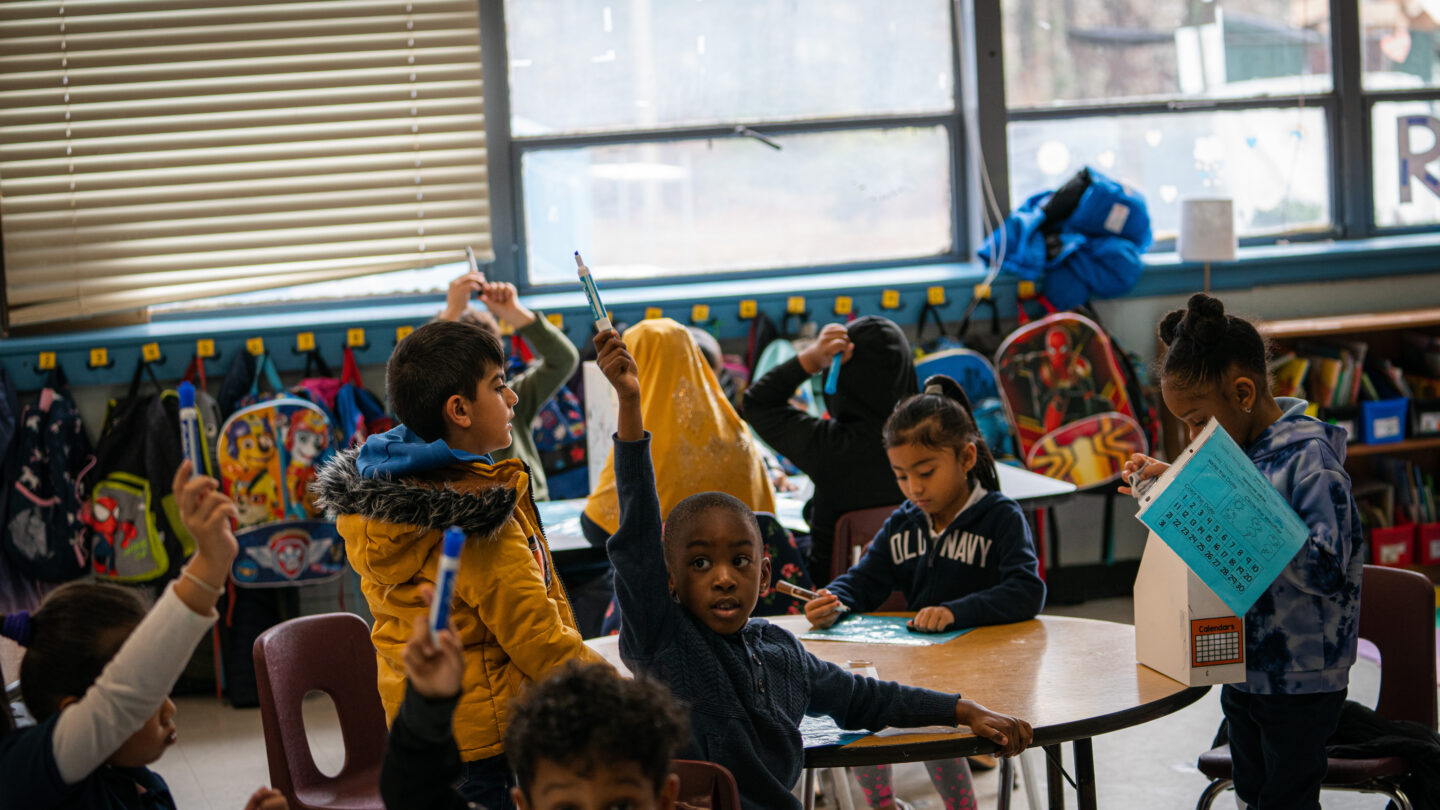

Dozens of second graders happily jostle their way toward the cafeteria at Decatur’s International Community School. They walk through a long hallway adorned with school projects, flags from different countries and pictures of people around the world. And they pass Scorch – the school’s bearded dragon.

Sima Niroula is headed in the other direction. She’s a kindergarten teaching assistant, and she’s heading back to her classroom where kids are getting ready for a brain break.

Niroula is one of three women in a new pilot program that is retraining incoming professionals who immigrated from other countries to be teachers.

“Back in my country, I used to work in different national and international not-for-profit organizations,” she said. “When I came here with my family, we left everything back in my country. We have to start from the root level. We don’t have anything.”

Niroula hails from Nepal, and her situation is one many immigrants and refugees face when they come to the U.S. People with college degrees and professional accolades almost always have to rebuild their careers from scratch.

Another teaching assistant at ICS, Shakila Aimaq, faced the same dilemma. She fled Afghanistan after the U.S. pulled out of the country. She had just finished her medical education and was about to start clinical rotations when she and her family had to flee and ended up in Atlanta.

“When we came here… just all of my dreams… gone,” she said. “I cannot work as a doctor. And somebody told me that they ‘are not going to accept your degrees in medicine here.’”

Aimaq would need to start medical school over again in the U.S. to continue her planned career path – an option that is not really an option because of prohibitive costs and time.

Instead, she joined the teaching program – a collaboration between the Refugee Women’s Network and ICS.

ICS is a different kind of school. Students come from more than 30 countries – some are refugees, some are kids of immigrants, and some are born and raised here.

Fran Carroll, the interim executive director of the school, said the school follows one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s main ethos – the beloved community where everyone takes care of one another.

“What we wanted to do was answer two potential issues, which is the teacher shortage as well as providing employment opportunities for people within our community,” she said.

Federal Department of Education data shows Georgia has teacher shortages for every grade level in several subjects. At the same time, the state is home to thousands of resettled refugees.

“We also know that there are a lot of talented women who are coming to America for resettlement purposes, who in their home countries are educated,” Carroll said. “I mean, doctors, lawyers…the whole nine.”

Saadiyah Alani is another one of those educated and talented women who joined the teaching program. She’s originally from Iraq and already taught French and Arabic before coming to the U.S.

“When I came here and asked to work with my degrees, they said, ‘Oh, they didn’t accept your degrees because you’re from Iraq,’” she said. “I graduated. I studied. I worked hard jobs in my country, but it’s for nothing. So here I started other things. I started in a bakery making pastries.”

Alani and her cohort expressed many times the utmost gratitude they feel for the teaching program and the opportunity to reinvent themselves.

For 9 months, the three women will work on their teacher certification while assisting in a classroom. Next fall, they will be co-teachers. Within two years, they will be ready to teach in their own classrooms.

“They are very uniquely situated to address the teacher shortage,” said Sushma Barakoti, the executive director of the Refugee Women’s Network. “We really try to fill that gap as well as provide meaningful employment for women who have come here as refugees and are aspiring to move on with their lives and thrive in this country.”

Plus, Barakoti said, the kids at ICS see these teachers-in-training as role models. They come from the same countries, speak the same languages, and are examples of being brave when starting over in a new place.