Think You’re not a Sensation-Seeker? Think Again.

They cliff-dive. Run with the bulls. Drive ambulances. Chase tornadoes. We all know thrill-seekers when we meet them.

But even if you’re not an extreme thrill-seeker, there’s still probably some part of the larger concept to which thrill-seeking belongs that applies to you, too.

Click below to listen to Kate Sweeney’s radio story on sensation-seeking.

Broadcast version of story that aired Thursday, July 12, 2014

It’s this wider idea, of “sensation-seeking,” that’s the subject of a new online survey by Emory psychologist Ken Carter. He’s asking people to answer a series of 40 questions to learn what kind of sensation-seeker they are. It’s all to collect material for a new book he’s writing on the concept, aimed at the general public.

Sensation-seeking, which was first introduced to the world by psychologist Marvin Zuckerman in the 1960s, refers simply to the human quest for experience.

It turns out there are actually four different kinds of sensation-seeking.

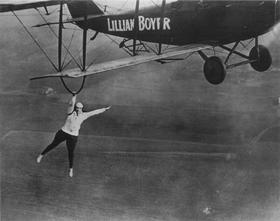

The first is thrill-seeking. “Thrill-seeking,” says Carter, “is really about those dangerous activities or risky activities—you know, like running from a bull or jumping out of a perfectly good plane.” Thrill-seekers are adrenaline junkies. But we knew that. Moving on.

The second category, disinhibition, has to do with your ability to be spontaneous. “People low in disinhibition are a little bit more controlled. They’re going to think through more of the consequences,” says Carter. They look before they leap. People high in disinhibition? They just leap.

The third kind of sensation-seeking is called boredom susceptibility, which boils down to one’s ability to tolerate the absence of external stimuli. In other words: to tolerate nothing. Dr. Carter’s preliminary findings actually show Georgians at large to be low in boredom susceptibility. As a state, we don’t get bored.

The fourth and fourth and final scale is called experience-seeking, which means the quest for new and novel experiences that challenge the mind and senses. “And this can come out in terms of travel to new places, trying new food, reading, or even daydreaming, for some people—in terms of thinking of what other people might be like or thinking about their lives.” So, novelists? Public radio fans? You, my friends, are experience-seekers.

But the import of sensation-seeking as a whole goes beyond learning and entertainment, says Carter, to have major impact in practical areas of our lives. “Being fearless and jumping out of a plane can also mean that you’re fearless in sticking up for someone, or when it’s time to do a presentation.” High sensation-seekers who have overcome their feelings of trepidation by traveling to new lands or bungee jumping, may just be more likely to tackle everyday situations that scare them, too—like, say, public speaking.

Interestingly enough, Carter himself rates low on the sensation-seeking scale in every area except experience seeking. As a low sensation-seeker, he says he’s fascinated with the stories and motives of the high sensation-seekers of this world.

“To be able to take a peek into how someone else is viewing the world and what they quest to do…is an amazing thing.” While he himself would never skydive, he loves to hear stories about the positive feelings this experience evokes in thrill-seekers. Just for that moment, he’s able to understand someone incredibly different from himself, from the inside out. He says, “It’s like having a different kind of life.”

Interested in finding out what kind of sensation-seeker you are? You can take Ken Carter’s online survey, or just learn more about his work here.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))