A Tiny Snail That Only Lived In Georgia Has Gone Extinct

This week, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published its finding that the beaverpond marstonia, which lived in southwest Georgia, is now extinct.

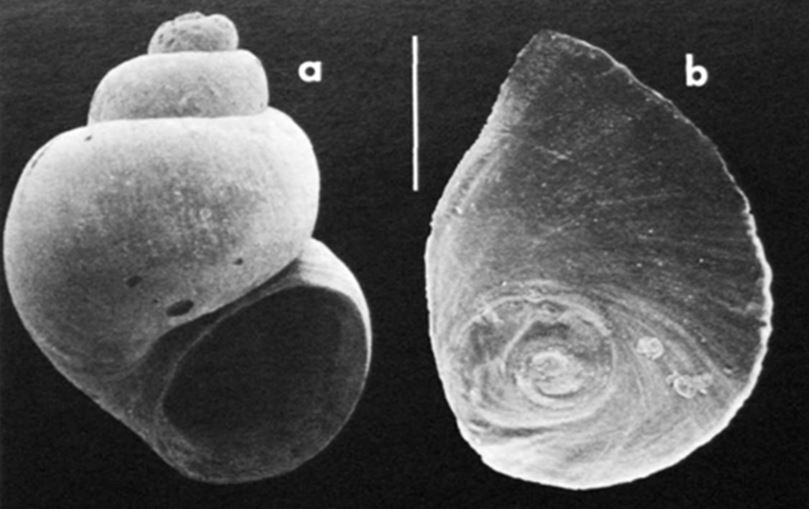

Photo by Robert Hershler/Smithsonian

A tiny snail that lived in southwest Georgia is gone. The beaverpond marstonia lived in a handful of creeks and streams near Lake Blackshear. This week, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published its finding that the species is now extinct.

The tan, whorled snail was “minute,” Fred Thompson wrote in his description of the species.

He was a curator at the Florida Museum of Natural History who discovered the beaverpond marstonia in the 1970s in, as he wrote, “a clear stream that flows through a cypress slough and drains into the east side of Lake Blackshear.”

The snail was just a few millimeters long, said Jason Wisniewski, senior aquatic biologist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources

“Smaller than a BB from somebody’s BB gun, or not much bigger than a few grains of salt,” Wisniewski said.

He’s never seen one, but he did search for them the past couple years. No scientist has documented the snail since the year 2000, and it may never have been very common.

“At no place was the snail abundant,” Thompson wrote in his 1977 article describing the species.

In 1984, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service put the snail on a list of species to consider protecting.

There it remained, a “candidate species,” until 2010 when the environmental group Center for Biological Diversity petitioned the federal agency to study hundreds of southeastern aquatic animals — including the beaverpond marstonia — and possibly protect them under the Endangered Species Act.

The Center for Biological Diversity then sued U.S. Fish and Wildlife in 2016 to force a decision on the snail.

That approach, of pushing for hundreds of species to be protected and then suing, has been controversial. Agencies say they’re strapped for staff and money as it is.

Tierra Curry, senior scientist with the Center for Biological Diversity, said it helps get protection for species like the tiny beaverpond marstonia that no one may be paying attention to otherwise.

“They should have been protected even decades before we submitted our petition. Even we were too late,” Curry said.

Georgia has an incredible range of freshwater species, and many of them could be threatened, Curry said.

“It’s kind of like the tropical rainforest or the coral reef. It’s this beautiful underwater world,” she said.

And there aren’t enough experts on all those fish, mollusks and other underwater creatures – including snails – said Wisniewski.

Thompson, the Florida curator who was the expert on the species, died last year.

Wisniewski said when he went back to the places where Thompson had found the underwater snails, many of them were dry. Drought and industrial or farm water use may have contributed to the snail’s extinction, he said.

“These droughts tend to be more frequent now, and of course whenever you have these droughts, there’s more demand for the water resources,” he said. “It kind of burns the candle on both ends.”

Though the beaverpond marstonia was miniscule, its loss could be an indicator of bigger issues in the environment, said Wisniewski. And scientists will never know what role it played in its ecosystem, since it hadn’t been well-studied.

“Any time we lose a species it’s really sad,” Curry said. “It means we made a mistake that can’t be corrected.”