Turtles, Fire and Contamination: Opposition From Spaceport Camden’s Neighbors

Russ Regnery is a Little Cumberland landowner who runs the island’s loggerhead sea turtle monitoring program. He’s worried about the impacts the spaceport could have on the species, and the island itself. (Emma Hurt/WABE)

This piece is a part of WABE’s deep dive into Camden County’s proposed spaceport project: how it came to be, who could be affected and where it could go from here. Read part one of this special report here.

The spaceport site sits just inland from Little Cumberland Island. Many of the 83 families who own land and homes on the protected barrier island aren’t happy about the idea of rockets launching over them.

One of their arguments involves the island’s loggerhead sea turtle monitoring program, the oldest continuous one in the world.

Russ Regnery, a Little Cumberland landowner and retired microbiologist, runs it today. He’s worried about the spaceport’s effects on the turtles.

“The first risk would be just the lights. Because that would be straight over there, and they would have lights going presumably often and lighting up that part of the horizon,” he said. “So the light pollution alone would be an issue. Even if they tried to mitigate it, it would still be an issue.”

Any artificial light can throw off turtle hatchlings’ course to the ocean.

But it’s not just the turtles some Little Cumberland landowners are worried about. It’s the island’s vulnerability to fire from debris of any exploding rockets.

Except for a few dozen houses and a historic lighthouse, the island is basically undeveloped, without much firefighting infrastructure. It has one water tank with about five minutes of spray and water-filled backpacks stored around the island.

Kevin Lang, vice president of the Little Cumberland Homeowners Association, called the firefighting resources “ample to handle fires from lightning strikes (our primary natural fire threat), but very inadequate to address a multi-point fire that you would expect from the debris field of an exploding rocket.”

He said the group was alarmed to discover in the county’s proposal that their houses were underneath some of the proposed rocket launch trajectories.

So they asked the county how that would work: “And the chairman of the commission (Jimmy Starline) told us that we ought to consider getting in a bunker,” he recalled.

“And we told him that we couldn’t put our cottages in the bunker and that we really weren’t interested in getting in a bunker. What we were more concerned about was the impact that an exploding rocket would have on the natural environment of the island, which is our primary concern.”

Jim Renner is also a Little Cumberland landowner and vocal spaceport opponent. He questions why they are being asked to take on risks from the county’s chosen project.

“An astronaut may make the decision to take that risk. The owner of a rocket company may choose to take the financial risk,” he said. “We’re uninvolved in this. Why should we have to bear any risk from this project?”

Then there’s big Cumberland Island next door. The National Park Service runs it as a protected National Seashore.

Carol Ruckdeschel, an environmental activist, lives on the north end of Cumberland year-round, and she said the spaceport just doesn’t make sense to her.

Parts of the island and waterways nearby would close every time a rocket launches, according to the draft environmental impact statement. It predicts 12 launches, landings, fire engine tests and dress rehearsals annually.

“It would just be a nightmare for the Park Service,” Ruckdeschel said. “And I don’t see how they could do it,” she said. “And the county is doing it. In other words, I live in the county, and I’m paying all this in my taxes.”

Personally, I’m probably the only one that lives there full time. And I’m right in the trajectory. And nobody from the spaceport’s ever talked to me.”

And what about the Park Service?

About 60,000 people visit Cumberland each year to camp and hike in the wilderness known for its live oaks, Spanish moss and wild horses. Many make ferry and camping reservations months in advance, and the county has prioritized expanding visitation.

The Park Service declined to speak publicly but submitted comments during the spaceport’s environmental review process.

In them, the agency said the spaceport would “directly, indirectly, and cumulatively adversely affect” the park. It wrote the plan would “have significant impacts to the wilderness character of this area due to increased noise, lighting and other man-made intrusions associated with spaceport operations.”

There’s another nearby constituency that could be affected by the spaceport: commercial fishermen. Several of them testified at a public meeting the Coast Guard held last fall about the proposed closure zone during launches.

Greg Hildreth is from Glynn County nearby, and has been a charter boat captain in the area for nearly three decades. He testified that a spaceport would “hurt my business.”

He said the area is “one of the biggest and most productive tarpon fishing spots in the United States or the world. And for some private entity to come in and try to take that away from me, my other fellow captains, and recreational anglers is unacceptable.”

Contamination

It’s the finances of the plan that caught the attention of Steve Weinkle.

He and his wife retired to Camden County in 2012 from metro Atlanta and designed their dream house overlooking the marsh. At that time, they didn’t know it could also be a great view to a proposed spaceport just down the road.

Weinkle said he first heard about the spaceport idea shortly after they moved.

“At that time, I thought it was kind of a cool idea because I really didn’t know about the Union Carbide property very much,” he said. “I knew that the Union Carbide property was just 6 miles down the road from where I live on the same road that I live on.”

Union Carbide is the chemical company that owns one of the pieces of land for the proposed spaceport. The county has already agreed to buy the Union Carbide land if they get a site operator license from the federal government. That’s the decision due by December.

Camden’s original purchase agreement with Union Carbide was for $4.8 million. The county commission has so far paid at least $1.9 million in purchase option money for it.

The land is one reason Weinkle has become a persistent voice in opposition to the project.

“I work a full-time job at it,” he said. “I put 40, 50, 60 hours a week into it. I write a weekly news blast. I write letters to the editor. I communicate with the FAA, Georgia [Environmental Protection Division]. I filter through thousands of pages of documents that I get under Open Records Acts.”

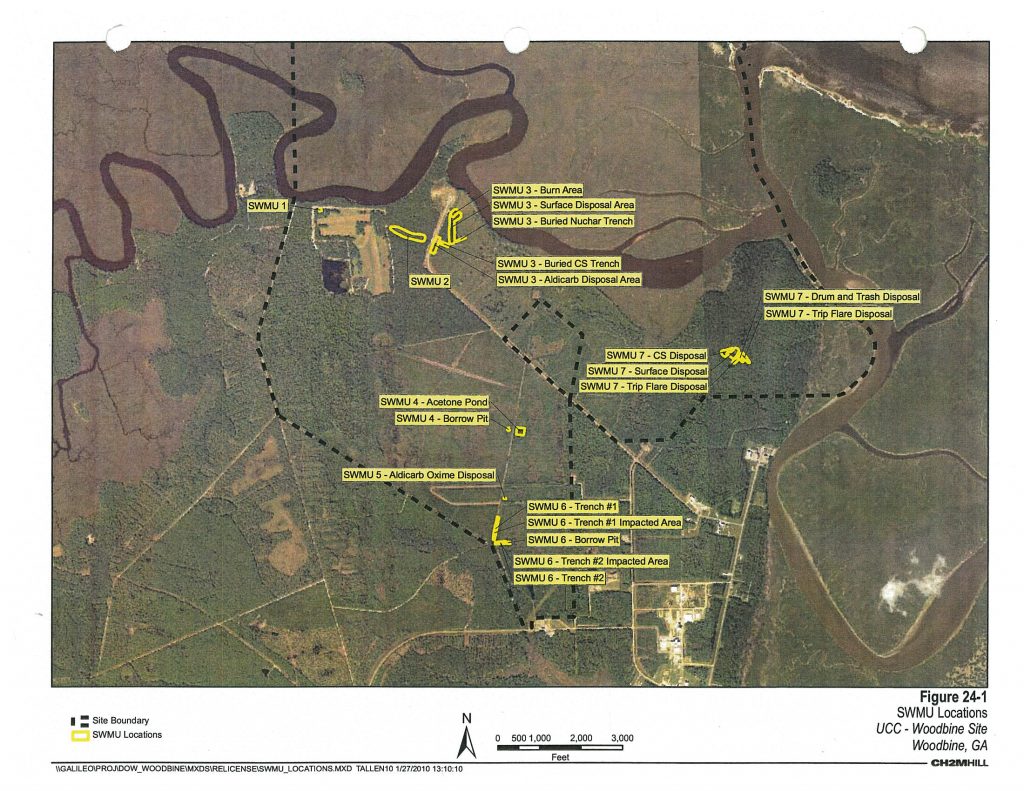

One focus of his research is the contamination of the land: the result of decades of munitions and pesticide production.

Union Carbide, now owned by Dow Chemical, has been working for three decades with state officials to clean up a hazardous waste landfill and other contaminated sites. The company is actively cleaning up unexploded munitions as well.

Because of the pollution, the state placed an environmental covenant on the property, which prohibits most uses of the groundwater, and any homes, schools or recreation facilities from ever being built.

The good news: according to the purchase agreement, if the county buys the land for the spaceport, it will not be responsible for any contamination that is now known.

But Weinkle wonders, what if more pollutants are found?

And how much will environmental insurance cost for a spaceport on that kind of property?

“As a person who loves where he lives and wants Camden County to prosper. I don’t want us to be burdened in the future with costs and liabilities that exceed our ability to pay for them,” he said.

Union Carbide declined to provide a figure of how much it has spent so far on the contamination at the Camden County property, but in January 2019, the company projected the next 30 years of work would cost it nearly $20 million.

Environmental groups including One Hundred Miles and the Satilla Riverkeeper have raised concerns about the pollution, too.

Weinkle is also worried about the other piece of land in the county’s spaceport plans, owned by Bayer Crop Science. There’s no purchase agreement in place, but the county’s proposal assumes ownership of that property and access to its dock.

Union Carbide sold off the parcel in 1986, but there hasn’t been anywhere near the cleanup on it. So, how polluted is the Bayer side? State records are slim, but Bayer did produce a pesticide there until 2012, when the Environmental Protection Agency decided the chemical was too dangerous to produce.

A 2016 Federal Aviation Administration document reviewed by WABE shows Bayer knows there is contamination on its site. But it doesn’t know exactly what, nor exactly where.

So per the document, when the county’s environmental contractors were asked to survey the land for the spaceport in 2016, they were afraid to go on the Bayer side of the property, for safety reasons.

The contamination doesn’t worry County Commissioner Gary Blount.

“Quite honestly, I think it has significant commercial value with or without the spaceport frankly. I mean I really do,” he said. “There are a lot of other commercial enterprises that can take place.”

Blount is not fazed by the opposition. He says change is always controversial.

“A lot of folks are in opposition to things,” he said. “It is change. I don’t care what you do. Change a street. Move a library. You want to get them fired up? Move a library.”

He compared the spaceport situation to when the naval base moved to the area. That’s Naval Submarine Base Kings Bay, about 10 miles south of the proposed spaceport site.

Many in Camden were against the idea, he said, and now the base is the county’s largest employer.

“What was great and exciting for a lot of people was misery and hatred for another. And I get it,” he said.

“The spaceport idea, you know, while I believe to be exciting and a tremendous opportunity, some folks see it as not because they want no change. They want to come in here and have it be just like it was as much as possible. And either you’re growing or you’re dying.”

Read part three of this special report here.