What’s the First Day of School Like for a Superintendent?

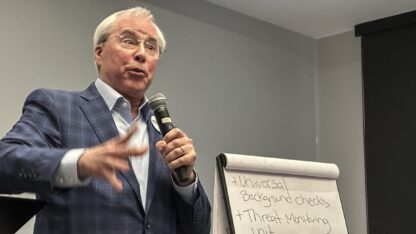

The first day of school for students and teachers can be exciting, busy, even nerve-wracking. But what’s it like for a school district leader? WABE’s Martha Dalton accompanied Fulton County Superintendent Dr. Robert Avossa during his first day of school to find out.

Hear the broadcast version of this story.

Starting Out

Avossa visited seven schools on the first day. But it’s clear from the start, this isn’t about him.

How are things running? He asks principals. Where are the gaps? What needs to go more smoothly?

He greets students, parents, staff members. He’s energetic, walks at a clip through the halls—observing, waving, saying hello.

Avossa starts out at Mimosa Elementary School in Roswell. 60% of the students are English Language Learners. Avossa knows plenty of them still haven’t registered.

On the way to his next stop, Roswell High School, he explains late registrations can create a headache for the district.

“We may need a new teacher at ABC Elementary School,” he says. “The problem with that is where are you going to find a teacher in the middle of August to take a job in your community? The reality is our parents do us a disservice when they don’t register their kids on time. And unfortunately, it’s usually in areas that are impoverished and really hard to staff anyway.”

Change is in the Air

The Fulton County School District is 90 miles long. It stretches from Milton, on the north side, to Palmetto on the southwest side. Central and North Fulton schools are generally more affluent and have good reputations. The South Fulton schools have historically served disadvantaged populations and have been lower-performing. But Avossa says that’s changing.

“For the first time, three high schools in South Fulton have higher graduation rates than two in North Fulton,” Avossa says.

That’s not because the north side schools are declining, he says. The south side schools are making gains.

As he drives to Roswell High, in North Fulton, Avossa says the school’s graduation rate was 68% four years ago. Last year it was 86%.

“We’re not letting kids walk away and dropping out easily,” he says. “We’re not doing it. Think about this, we spend $100,000 on average by ninth and tenth grade. Would you let a $100,000 investment just walk away, walk right out that door, without doing everything you can to reap a benefit?”

Roswell Principal Jerome Huff says, “No.” Avossa credits Huff and his staff for helping more kids graduate. Huff says the effort involved teachers, school counselors and even real estate agents, who he invited to the school one day.

“Some of them, you know, they talk about the school, and they don’t know,” Huff says. “‘Well, you know, you shouldn’t go to Roswell High,’ but they’ve never set foot in Roswell High. So, once they started seeing some of the numbers and the accolades we got, even though we do have at-risk kids, and we embrace those kids, I think it kind of opened their eyes. They had no idea.”

Huff admits there’s more work to do, but says his community is up to the task.

“It’s not fair to compare us to other North Fulton schools because we don’t look like other North Fulton schools,” He says. “But we hold our own.”

There’s evidence of that a few minutes later, when Avossa ducks his head into the counselor’s office. Parent Judy Davis is registering her daughter, Whitney, for school.

“We chose our neighborhood and our house specifically so we could attend Roswell High School,” Davis says. She goes on to say she was impressed with Mr. Huff when visiting from Oklahoma last spring.

Leadership Matters

That encounter reinforces another point Avossa repeatedly makes.

“‘Leadership matters,” he says. “It’s one of the most important decisions I make as superintendent, which is, ‘Who gets to join the team as principal?’“

If he picks the right leader, he says, everything else falls in place.

“Great teachers will stay and work for great principals, even in challenged environments,” Avossa says. “And poor teachers aggregate around bad principals because they let them do anything they want and they don’t hold them accountable.

Under Avossa’s leadership, Fulton’s graduation rate has increased four points since last year and the district now has Georgia’s second-highest SAT scores.

Reflecting on his four years with Fulton, Avossa notes he’s one of the longest-serving school leaders in the metro area. DeKalb, Clayton, and Cobb counties and the Atlanta Public Schools all have superintendents newer than him.

“All of a sudden, I went from being a rookie to being one of the senior superintendents in the area,” he says.

Charting a New Course

Early on, Avossa led Fulton through the transition of becoming the state’s largest charter district. The status gives individual schools more autonomy. The district can also receive waivers from some state requirements. With 100 schools and more than 96,000 students, Avossa says the designation makes sense for Fulton. Schools are run locally, he says.

“There’s nothing easy about the process, but I will tell you with ¾ of the schools now working in this new autonomous space, you’re beginning to really see the energy around what I call developing ‘ownership’ of the schools,” he says. “Parents and students are authentically engaged in the strategic plan, what they should focus on, rather than the central office saying, ‘Here’s how we want you to run the school.’”

Being a charter district has also allowed Fulton to establish a seed fund through which schools can apply for grants. Avossa stops next at Centennial High School, which used a grant to create a 21st century technology hub for students. Kibbe Crumbley is Centennial’s principal.

“We wanted them to be able to walk into a learning commons, which isn’t the old school library or media center, but actually a hub where they can work, they can have distance learning, they can have hybrid learning, they can do all kinds of blended environments,” Crumbley says. “So we created an environment that will hopefully house and shape their ability to have the personalized learning.”

The hope is this kind of innovation will spread across the district.

Avossa’s short-term goal is to iron out wrinkles. But it’s clear he’s thinking long-term. He wants Fulton to become a model in the region.

And the superintendent, who has four schools left and a four hour debriefing after that, doesn’t seem willing to slow down until then.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))