New Mexico is pushing to be a 'model' for how race is taught in U.S. schools

ALBUQUERQUE (AP) — A proposal to overhaul New Mexico’s social studies standards has stirred debate over how race should be taught in schools, with thousands of parents and teachers weighing in on changes that would dramatically increase instruction related to racial and social identity beginning in kindergarten.

The revisions in the state are ambitious. New Mexico officials say they hope their standards can be a model for the country of social studies teaching that is culturally responsive, as student populations grow increasingly diverse.

As elsewhere, the move toward more open discussion of race has prompted angry rebukes, with some critics blasting it as racist or Marxist. But the responses also provide a window into how others are wrestling with how and when race should be taught to children beyond the polarizing debates over material branded as “critical race theory.”

The responses have not broken down along racial lines, with Indigenous and Latino parents among those expressing concern in one of the country’s least racially segregated states. While debates elsewhere have centered on the teaching of enslavement of Black people, some discussions in New Mexico, which is 49% Hispanic and 11% Native American, have focused on the legacy of Spanish conquistadors.

“We refuse to be categorized as victims or oppressors,” wrote Michael Franco, a retired Hispanic air traffic controller in Albuquerque who said the standards appeared aimed at categorizing children by race and ethnicity and undercutting the narrative of the American Dream.

The New Mexico Public Education Department’s proposed standards are aimed at making civics, history, and geography more inclusive of the state’s population so that students feel at home in the curriculum and prepared for a diverse society, according to public statements.

“Our out-of-date standards leave New Mexico students with an incomplete understanding of the complex, multicultural world they live in,” Public Education Secretary Designate Kurt Steinhaus said. “It’s our duty to provide them with a complete education based on known facts. That’s what these proposed standards will do.”

The plan calls for students to learn about different “identity groups” in kindergarten and “unequal power relations” in later grades. One part of the draft standards would require high school students to “assess how social policies and economic forces offer privilege or systemic inequity” for opportunities for members of identity groups. In a first for the state, ethnic studies and the history of the LGBT rights movement also would be introduced into the curriculum.

An Albuquerque pastor, Rev. Sylvia Miller-Mutia, welcomed the change in her written comment, arguing children see race early, and that learning about it in school can dismantle stereotypes early. When her eldest child was 3, she said that her Filipino dad wasn’t American because he has dark skin, while her mother was American because she has light skin.

“Already, a cultural script that said to be American is to be light-skinned had somehow seeped into my preschooler’s consciousness,” Miller-Mutia said in an interview.

Many Democratic-run states across the country are looking to diversify those cultural scripts, while Republican-run ones are putting up guardrails against possible changes. California was among the first states last year to make ethnic studies a graduation requirement. Texas passed a law requiring teachers to present multiple perspectives on all issues and one Indiana lawmaker proposed that teachers be required to take a “neutral” position.

The education department in New Mexico is reviewing over 1,300 letters on the proposed standards along with dozens of comments from an online forum in November. The standards were written with input from 64 people around the state, mostly social studies teachers, and are to be published next spring with revisions.

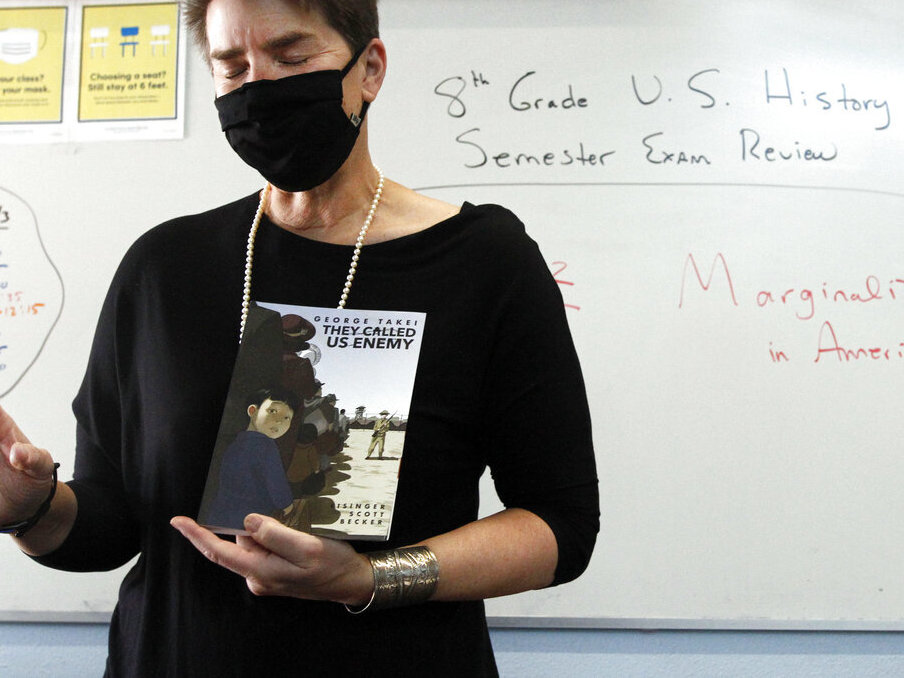

Among the authors was Wendy Leighton, a Santa Fe middle school history teacher. As a leader of the revisions for the history section of the standards, she said the goal was to take marginalized groups like indigenous, LGBTQ and other people “that are often not in textbooks or pushed to the side and making them kind of more closer to the center.”

Identity was the center of a class she taught in December, where students learning about the Salem witch trials identified which groups were at the center of power — clergy, men — and which were on the margins — women, servants.

“What’s a marginalized group in America today?” she asked the class.

State Republicans have argued that parents should teach their children sensitive topics like race and that there are bigger priorities in a state that ranks toward the bottom in academic achievement.

“The focus that I feel is urgent is math, reading and writing. Not social studies standards,” said state Rep. Rebecca Dow, one of six candidates for the Republican nomination for governor next year, hoping to unseat Democratic incumbent Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham.

Some parents who wrote public comments said they would rather homeschool their children than have them learn under the proposed standards.

“Struggle and adversity have never been limited to one specific race or ethnicity. Neither has privilege,” wrote Lucas Tieme, a father of five public school students, who are white.

Tieme, a bus driver for Rio Rancho public schools, said his wife was homeschooled so they’d be ready to take their kids out of school if it came to that.

Some parents who support the changes generally are skeptical of introducing race for the youngest students.

Sheldon Pickering, 41, has two adopted children who are Black, and has seen casual racism against his kids escalate as they reach adolescence in Farmington, near the southeast corner of Utah and the eastern part of the Navajo Nation. He has had “the talk” with his Black son, instructing him how to interact with police. But Pickering, who is white, worries about schools introducing too much too soon.

“If we start too early, we rob kids of this rare time in their life that they have just to be kids,” said Pickering, a cleaning business owner. “They just get to be these amazing little kids and enjoy life without preconceived notions, without context.”

___

Attanasio is a corps member for the Associated Press/Report for America Statehouse News Initiative. Report for America is a nonprofit national service program that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on under-covered issues. Follow Attanasio on Twitter.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))