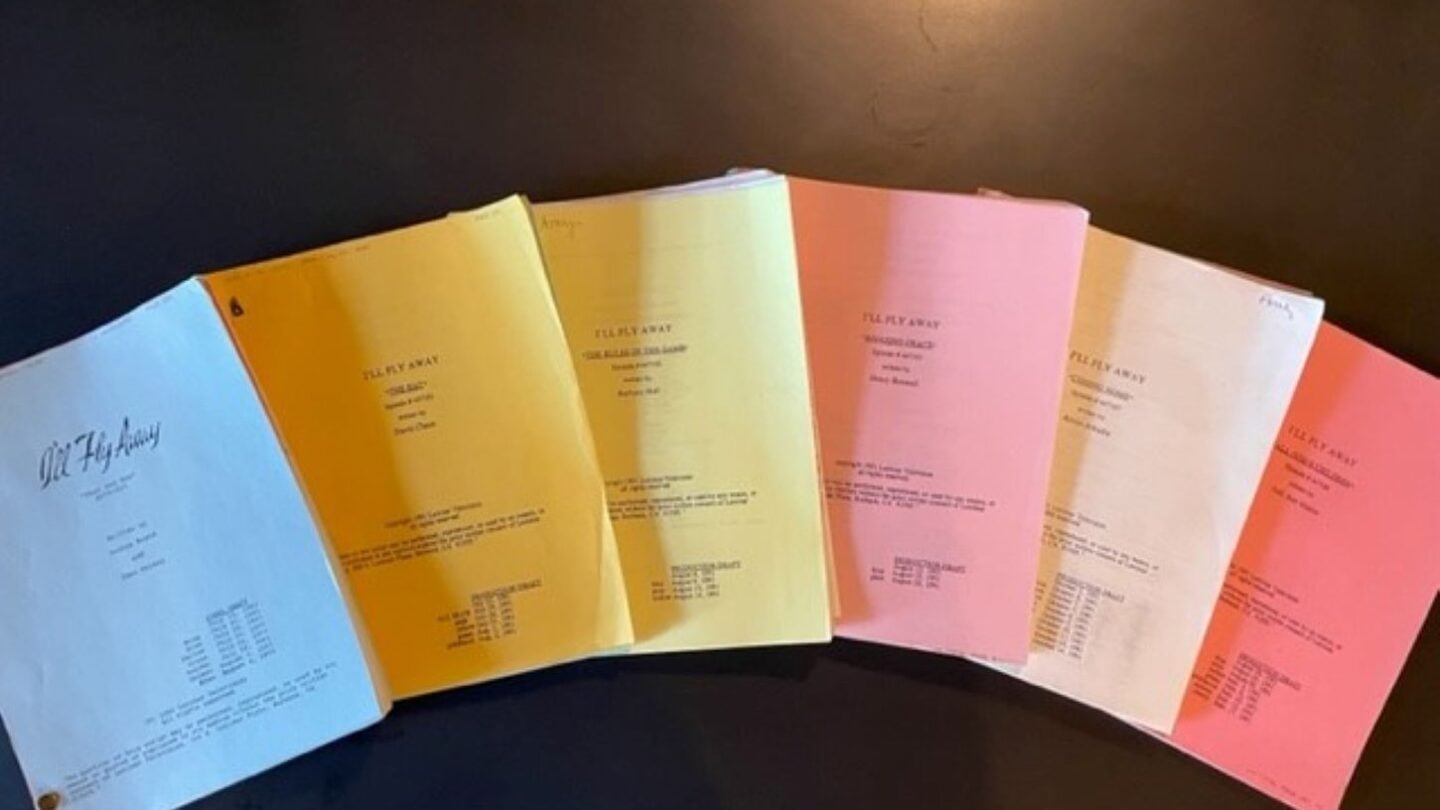

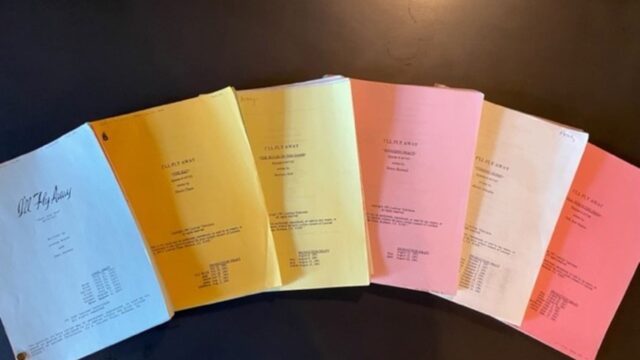

In the summer of 1992, cast and crew of the NBC series “I’ll Fly Away” returned to “Lorimar Hollywood South,” a warehouse converted to a makeshift soundstage outside of Stone Mountain, to begin production on the show’s second season.

The program, which starred veteran actor Sam Waterston as Forrest Bedford, the district attorney of the fictional town of Bryland, Georgia and actress Regina Taylor as his family’s housekeeper, Lily, explored racial relations and the rise of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 1960s South. It received rave reviews in its first season and various accolade nominations.

Despite the critical fanfare, the show struggled in ratings to find a stable audience.

“‘I’ll Fly Away’ was very much ahead of its time,” said Lester Dragstedt, dolly grip for the series. “All of the characters were deeply flawed, much more nuanced and complex (than other shows). It was much more kind of rooted in reality, and it took a while for audiences to understand that newer style of programming.”

A Reality More Unsettling Than Fiction

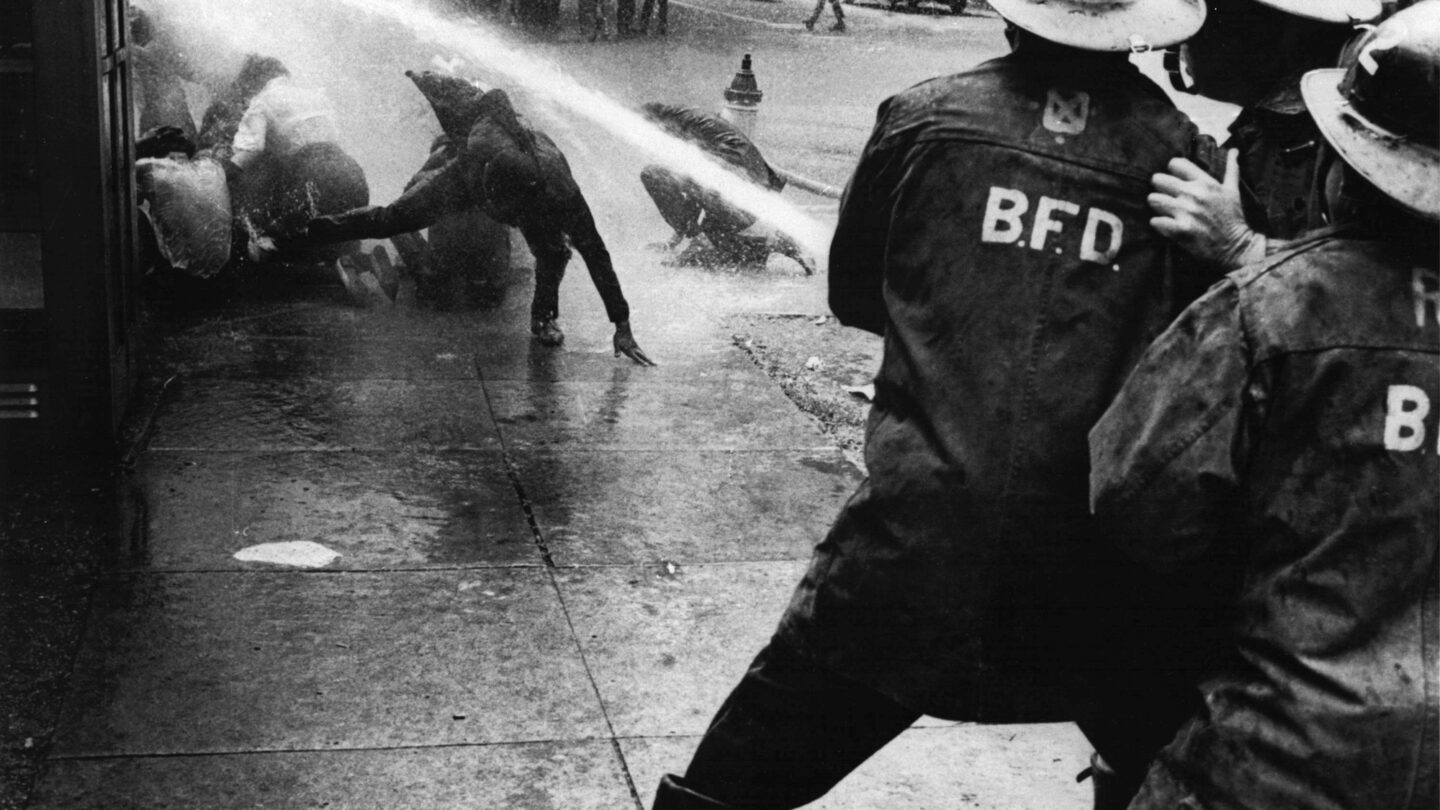

Led by showrunner David Chase creator of “The Sopranos,” “I’ll Fly Away” became notable for its authentic storytelling, rarely shying away from depictions of police brutality, segregation and other monumental moments within the Civil Rights Movement.

For many members of the cast and crew, the stories were often painful to recreate but necessary to be told.

“To feel the root of that hatred…we really were in shock.”

Ashlee Levitch, Actress who played Francie Bedford

“Sometimes when you’re shooting, you know in your mind it’s not real…but on set, you are feeling the energy, holding onto the actor’s words and believing the moment. You carry that experience with you as if you lived it,” said Amy Lacy, script supervisor for the series’ second season.

A key scene that left an impact on then-child actress Ashlee Levitch featured Klu Klux Klan members burning a cross in the Bedford family’s front yard in opposition to the political opinions of the family patriarch.

“We were actors, we read the script, we knew what was going to happen, but…to feel the root of that hatred, we really were in shock,” said Levitch. “I can literally feel just all of us standing on that porch. That’s when I really understood the gravity of what the show was really about.”

Unfortunately, acts of racism and inequality were not just exclusive to recreating events set in the late 1950s. For actress Rae’Vin Larrymore Kelly, who portrayed Lily Harper’s five-year-old daughter, Adeline, attending a predominately white preschool while working on the series caused her to see firsthand the prejudices that were still prevalent in the 1990s South.

“When I came in the class, some of the kids would look at me and be like ‘you can’t sit here…you can’t be my friend anymore, cause my mommy said no n*****s can be my friend.’ I asked my mom what the n-word was because I had never heard it before, but I knew that it wasn’t good,” said Kelly, who was four years old at the time.

“I remember this little blonde boy cut me in line at the water fountain. I said ‘hey, you cutted’ and he turned to me as if it was nothing and said to me ‘my granny told me that darkies go to the back of the line.’ We didn’t have ‘colored’ and ‘whites only’ signs in 1992 Atlanta, but I did have my best friend Shannon not invite me to her birthday party and tell me that she had to stop being my friend because I had a ‘black heart’ and that she could not trust me.

When you look at the show, you may be thinking about what heavy subject matters for Rae’Vin and (co-star) John Aaron (Bennett) to be dealing with at such a young age, but the reality was, for me, it wasn’t like I had to reach to feel that pain of being different, or being treated less than.”

A Role ‘Taylor’ Made

The character that typically came face to face with these types of injustices onscreen was the character of Lily Harper. Opening and closing each episode with a narration from her diary, the housekeeper and divorced mother finds herself throughout the series being drawn into the center of the Civil Rights Movement, from unsurely attending a silent protest at the end of the pilot to helping to lead a protest integrating a local college at the end of the series.

A Texas-born playwright and actress, Taylor was immediately drawn to the opportunity to tell the story of a woman who had not yet been represented on television.

The NAACP Image Award-winning actress felt that the role allowed her to pay tribute to the stories, struggles and strength that she had observed from the women within her life, even wearing her grandmother’s dress to all of the auditions for the character.

“I thought that it was a really amazing choice, especially at the time when we shot it, to have her speak from her diary at the beginning of each week,” said Taylor, who recently took on the role of Marian Shields Robinson opposite Viola Davis in the Showtime series “The First Lady.”

“You see her not only as hands, but fully embodied, fully fleshed out, and you see this mind as well…you saw that she had dreams. You saw her outside the white family that she took care of; you saw her in her community, with her father and her daughter and her friends; she had a love life. It took a Black woman into the center of this story, that has been figured into the history of cinema into the stereotype of the maid, and it turned that stereotype on its ear.”

Much like her character’s on-screen relationship with the Bedford children, Taylor left a strong impact on her young co-stars.

“Regina Taylor was a master class teacher for me,” said John Aaron Bennett, who played the role of the youngest Bedford child, John Morgan.

“Every step along the way, if there was a question that I didn’t understand, or if there was a moment where I was an ignorant young white boy who asked an out-of-line question, she had the grace, almost like a mother, to unpack those things for me. There were times I would say ‘I’m glad (racial inequality) is all over with,’ and she was really great in reminding us that the work was not finished yet.”

“It was too much truth, and they had to let it go…”

Elisabeth Omilami, Activist/Actress who played Joelyn

‘In Living Color’

The work for progressiveness was just as prevalent to the series onscreen as it was off.

“I have to give credit to the producers in that we did have conversations about the set-up of Lily Harper and they were open to these conversations with an African American woman, and bringing African Americans into the room, actually having conservations with Black people and having them involved in the development, which was groundbreaking in that point of time,” said Taylor.

In addition to creating a production apprenticeship for Morehouse College and Clark Atlanta University students to work on the show’s crew, Chase and producer Ian Sander made it a priority to bring on directors of color to oversee roughly 20% of episodes per season, including former actor Eric Laneuville, who went on to win one of the shows few Emmy Awards for his direction of a season one episode in 1992.

Accolades for the show’s creative talent continued in early 1993 when Regina Taylor won a Golden Globe Award for Best Lead Actress – Drama for her work on the show’s second season, becoming the first Black woman in history to win the honor.

Unfortunately, the continuing recognition and award wins failed to boast viewer ratings and the series, which received five different time slot changes over its two seasons on-air, was canceled by NBC in the spring of 1993. To many associated with the show, the cancellation was sad but expected.

“(The characters) inspired people to have empathy, and invited people to question their own lives, and how they may participate in this life.”

Regina Taylor, Playwright/Actress who played Lily Harper

“I always felt that it was canceled because (the stories) were too true, and they didn’t want to see that on TV,” said Elisabeth Omilami, daughter of Civil Rights activist Hosea Williams and a recurring actress on the series in the role of Lily’s friend and neighbor Joelyn. “There were things that they wanted Black women and Black people doing on TV that ‘I’ll Fly Away’ was slapping in the face of. It was too much truth, and they had to let it go.”

A Legacy That Soars

Although it has been 29 years since the series aired its final episode, the relevance of racial injustice and brutality of law enforcement remains as prominent now in the United States as it did during the time period that the series reflected on.

“Personally, I think there’s a sadness that we are looking at George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor and you see these stories in the news, and it hurts to know that we were back in 91’ and 92’ telling stories that happened in 1958 to 1962, we were telling stories that happened 30 years before our time. Now, 30 years later, we still have those stories to be told,” said series set decorator Amy McGary.

“There is still outrageous racism within this country, incredible white supremacy, voter suppression, we see it all over the place,” said Deborah Hedwall, a New York actress who played the role of the Bedfords’ matriarch Gwen.

With a resurgence on YouTube and social media, cast and crew members hope that the series will continue to shine a lot on those who changed history within the past and inspire those who are witnessing injustices of the present.

“This series, these characters…they inspired people to have empathy and invited people to question their own lives, and how they may participate in this life. It provided a hope for the future, in terms of particularly race relations in this country,” said Taylor. “I feel very blessed, very fortunate and very humbled by being a part of a series that is still relevant, especially now. It’s right on time.”