How Some Atlanta Restaurants Have Pivoted During The Crisis

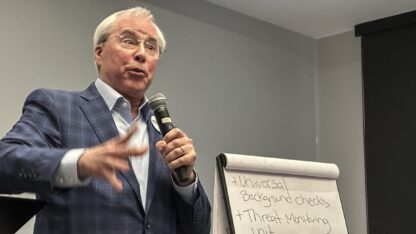

Michael Lennox, the founder of the company that owns Atlanta restaurants Ladybird, Golden Eagle and Muchacho, has started a nonprofit called ATL Family Meal to cook and deliver food to out-of-work employees from his and other participating restaurants.

Courtesy of ATL Family Meal

Gov. Brian Kemp says restaurants can begin opening for dining-in again this Monday.

Many restaurateurs in Atlanta say they’re not ready to take that risk, even though shelter-in-place orders have been especially tough on the industry.

In the past month, restaurants have temporarily closed. Others have switched to carry-out and delivery only. And a handful have figured out other ways to survive and adapt in the meantime, pivoting their businesses to work in the current world.

Listening To The Community

When it first became clear that places were either going to have to close or change, Krystle Rodriguez, who owns Hodgepodge Coffeehouse in Atlanta, says she was worried about her employees and also about the future of the business.

“Sales had slowed down so much that the idea of closing kind of made it feel like we might not be able to open back up,” she says.

Open or closed, she’d still have loans, utilities and credit card payments to make.

“We definitely just sort of took it day by day to try to figure out how to make it work,” she says.

But then she started getting ideas from conversations she was having with friends, customers and even with her landlord.

“You know, letting us know, ‘Hey, Krystle, it’s weird, like I can’t get all-purpose flour anymore,’” she says. “And so I thought, ‘Well, we can. We get that stuff all the time.’”

So, in addition to switching to a carry-out menu, Hodgepodge started repackaging its bulk flour and yeast to sell to customers. The coffee shop is selling the toilet paper it gets from its wholesalers.

It’s also distributing masks sewn by locals, and Rodriguez is letting a nonprofit use some of her space to bake bread to distribute to homeless people.

“I guess it just kind of goes with the name. I mean, we’re a hodgepodge,” she says.

Helping Other Businesses

A handful of other places around town are taking a similar approach, turning from restaurants into markets.

In Atlanta’s Kirkwood neighborhood, Sun In My Belly is normally a brunch spot with lines out the door on the weekends. Now, like Hodgepodge, it’s selling dry goods, paper towels and toilet paper. It also has produce and wine and beer.

“Similarly to most businesses, we’re seeing how life can be done differently,” says café manager Matt DeBusschere.

He says the restaurant made the change pretty suddenly; owner Max LeBlanc walked in with the idea, “and we all just got behind his energy,” DeBusschere says. “Probably in literally an hour, we transformed our entire business model.”

A key part of what they’re doing is inviting other Atlanta businesses to sell their goods out of what was a dining room and is now basically a general store. There’s a local chocolate company, a coffee roaster, potted houseplants and handmade soap and hand sanitizer. A flower shop is coming soon.

“We just want people to be able to walk through and be reminded that not only do we need their help, but there are so many other small businesses in Atlanta that need to be seen,” DeBusschere says.

And he says Sun In My Belly’s business is actually doing well.

“We expected revenues to dip to a fraction of what we’re used to, and somehow we are on par with all of our other months before this pandemic hit,” he says.

Feeding The Food Industry

Still, a lot of people who work in food service are hurting. And another pivot Atlanta restaurants have made is to feed their own workers and others in the industry.

Staplehouse, a restaurant in Inman Park, is providing meals to food service workers who can’t work. Many others are giving out meals and groceries as they are able.

“We’re talking about a very fragile social environment for lots and lots of people that may or may not know where their next meal is going to come from,” says Michael Lennox, the founder of the company that owns Atlanta restaurants Ladybird, Golden Eagle and Muchacho.

More recently, he’s started a nonprofit called ATL Family Meal to cook and deliver food to out-of-work employees from his and other participating restaurants.

“We, more than anything, are trying to make sure that this can be a stabilizing force for them and a source of comfort and hope,” he says.

Lennox says the pandemic has “galvanized” his feelings about wanting to see a better safety net for workers in the hospitality industry.

“I don’t think that that’s any particularly revolutionary idea or insight,” he says. “A lot of people have recognized for a very long time that the hospitality community is a pretty vulnerable one from an economic perspective. You got tons of people, the majority that work on tips or low hourly wages, no health insurance, no benefits. It’s really hard work.”

Supporting Health Care Workers – And Farmers

Other Atlanta restaurants are providing food to health care workers.

Forza Storico and Miller Union got a grant from State Farm and the Hawks to make boxed meals for Emory Healthcare employees.

Steven Satterfield, executive chef and co-owner of Miller Union, says the restaurant has transformed into an assembly line.

“The dining room is filled with, on one side, all of our to-go containers that are used to pack up the food,” he says. “We have a little dining nook that is the bagging area.”

He says beyond being able to feed health care workers, and keep most of his employees on the payroll, the effort also means he can support the farms that supply his food.

“We have long-standing relationships with these people, and they’re in just as tight of a situation as we are,” he says. “It’s springtime and they’re growing a lot of food, and they lost probably 80% of their wholesale accounts.”

Satterfield says he doesn’t know what the future looks like for restaurants, but he’s not surprised that so many places have figured out ways to adapt.

“Restaurant owners and chefs are very resourceful and inventive when it comes to being able to react to change. And so that’s one of the strong points of this type of breed of person,” he says. “We can be scrappy.”