On St. Simons Island, the pier sticks right out from the village. Near restaurants and T-shirt shops, jutting out over rocks piled to protect the shore from erosion, the pier is a popular spot for fishing.

James McBride of Savannah was there recently with a few of his grandchildren. He’s worked at International Paper for more than 40 years and has been fishing on St. Simons for almost that long.

“I’ve been coming out here probably about 30 years or better,” he said. “It’s a peaceful place. There’s a sense of peace that I get that you just don’t get it everywhere.”

Much of Georgia’s coast has that peaceful feeling: the sandy woods with the twisted live oak trees, the salt marsh with its fiddler crabs and birds, the windy dunes, the barrier islands. A lot of Georgia’s coastline is protected, and that’s a good thing when it comes to sea level rise because that makes the coast more resilient.

The water level has already gone up about 9 inches in Georgia since the 1930s, and it could rise by another 3 feet or more by the end of the century. While sea level rise threatens Georgia homes, infrastructure and even historic sites, Georgia’s natural places may be in a better position to absorb the changes.

Always Changing …

“The systems will naturally respond to sea level rise,” said Jason Lee, program manager for the wildlife conservation section at the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

The natural places on Georgia’s coast are all about change, he said. And if left alone, they can keep changing.

“The Georgia coast is probably the epitome of a dynamic habitat. Constantly moving, constantly changing,” he said.

On a sliver of a sandbar of an island, called Little Egg Island Bar, birds pile in to rest and wait out the high tide. This island, like much of the coast, is important to shore birds. And as sea levels rise, it’s low enough that it could be submerged.

There’s another thing that’s going on with the islands in this area right now, aside from sea level rise. A lot of the sediment they’re made of comes from the Altamaha River. Tons of dirt washes down the river, and has been since Georgia’s cotton-growing era. But less sediment flows down now, so some places like Little Egg Island Bar aren’t getting as built up by it as they used to.

But Little Egg Island Bar isn’t going to just sit there, washing away and slowly drowning. Lee said Little Egg Island Bar will likely shift.

All the barrier islands move around. They can form all of a sudden after a storm – actually another island did form all of a sudden, after Hurricane Irma – and they can disappear, too.

The Georgia coast is probably the epitome of a dynamic habitat. Constantly moving, constantly changing.

Jason Lee, Georgia Department of Natural Resources

“They grow and they shrink,” Lee said. “They erode here and accrete there.”

The beaches will move, too, as will the marshes. They’ll creep uphill and inland as the ocean moves in.

“Wherever the land meets the ocean, is where your beach is going to be,” Lee said.

Georgia’s beaches and marshes can adapt, and they have before. In some places, there’s visible evidence of where it’s happened in the past.

“Anyone that drives across the marsh sees old dead trees out in the marsh. You’re looking at old islands that have been captured and subsumed by rising sea level,” said Clark Alexander, a coastal geologist at the University of Georgia and head of its Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

… Except Where It Can’t

There’s a big “but,” though, with all of this. The natural places can adapt, except for when man-made structures keep them from changing.

The beach can’t easily move past or into places that are paved over or protected by sea walls, places where people are trying to keep the ocean out. No one wants the marsh to just up and move into downtown Brunswick.

“Those are areas that we’re going to continue to protect,” Alexander said. “We’re not going to abandon those areas. So there are some areas where we will lose the marsh.”

Still, a lot of the land on Georgia’s coast has been protected from development. This isn’t Miami, where high rises line the shore.

“We’re lucky to have so much wonderful green space on the coast currently,” said Ashby Nix Worley with The Nature Conservancy. She works with coastal Georgia cities and counties to figure out ways they can adapt that don’t impede nature — for instance, using oyster beds to reinforce shorelines instead of, say, concrete.

“We’re kind of at a point right now where we can use that to our advantage and really be proactive and, you know, preserving important areas and planning our communities in a smart way.”

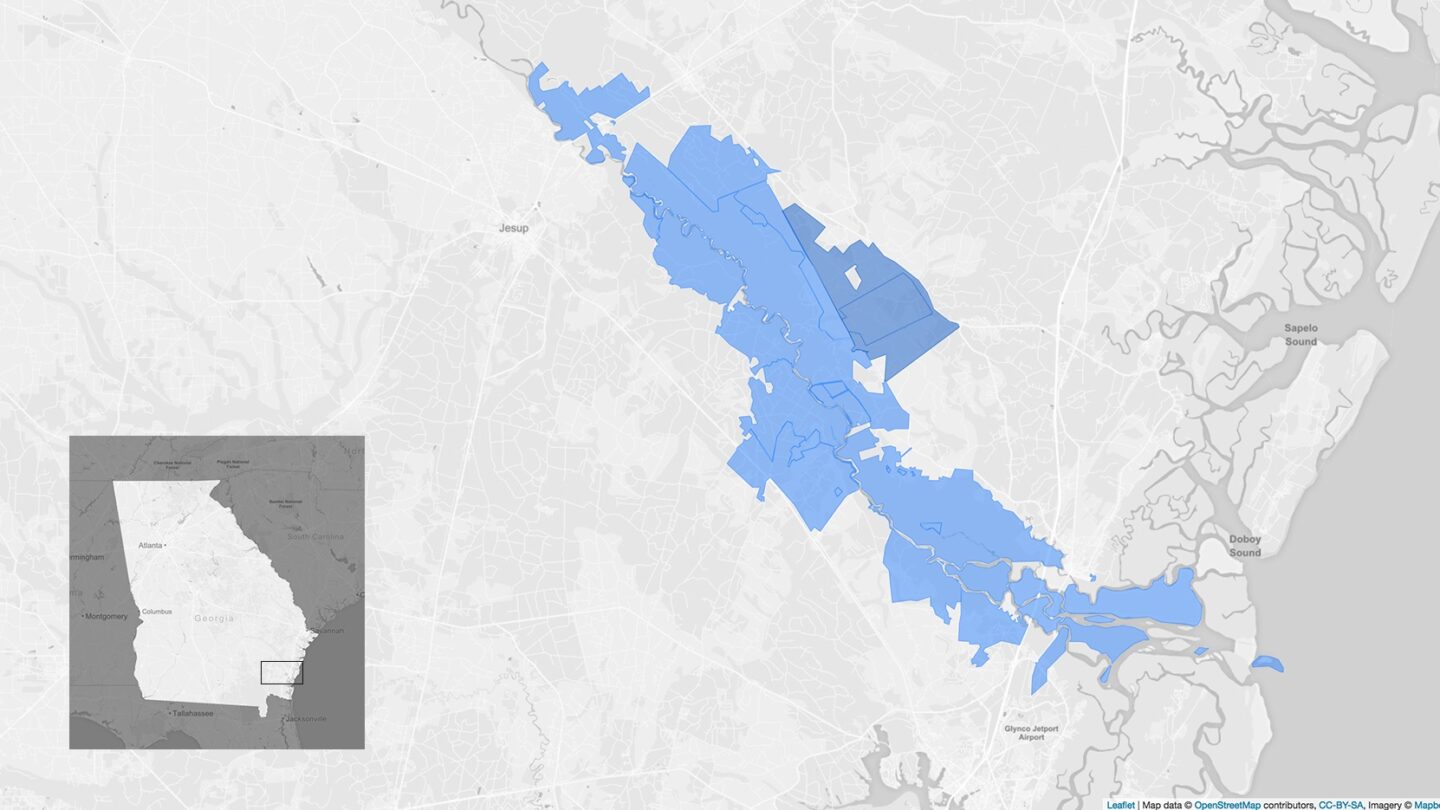

The state has been buying property that could help, too. DNR has worked to protect 40 miles of land along the banks of the Altamaha River. The main motivations are to buy land for recreation and for endangered species, but the corridor will give the marshes room to migrate inland from the ocean.

“Probably the systems that have been here for eons will be OK,” Lee said. “It’s our developments and it’s our human footprint that’s going to have to accommodate if sea level rise continues at the rate it is.”

Yes, some individual species will likely lose out, said Lee. And people who live on the coast are already feeling the effects of increased flooding. But the natural places on the Georgia coast overall, they’ll always be somewhere, if not necessarily where they are now.

Emma Hurt contributed to this report.