Listen to WABE’s investigation following Forest Cove residents over the last year as a serial podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music and more.

A federally-subsidized complex has become the symbol of substandard living conditions in Atlanta. At Forest Cove, half the 396 units are vacant, with many burned, full of trash or partially collapsed. In a recent year-long investigation, WABE reported how the residents who are left deal with collapsed floors, infestations and recurring shootings.

The city and the private owner, a company called Millennia, which bought the apartments in April 2021, have since started a plan to relocate the remaining tenants to other housing. Residents are set to leave this summer after years of living in units in disrepair.

But the neglect that led to Forest Cove’s current crisis may have been in the making for decades. Reviewing the property’s history in local and federal archives, WABE has found mismanagement as old as the complex itself.

It was the late 1960s when officials first mentioned the possibility of a new development next to the federal prison in Southeast Atlanta.

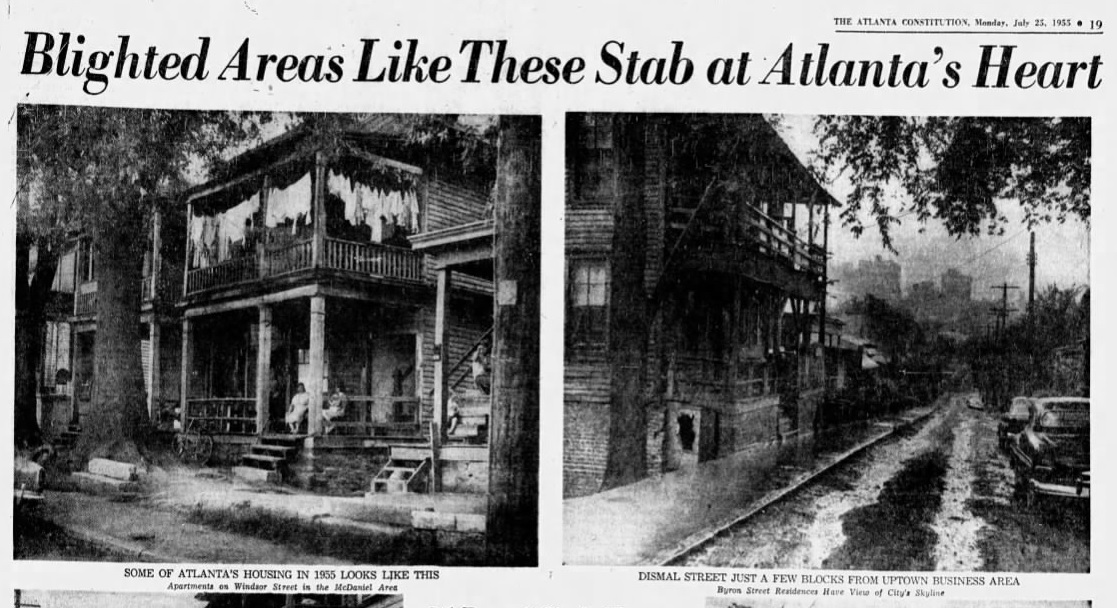

This was the era of the federal program known as urban renewal. Atlanta leaders were taking full advantage, pushing to demolish neighborhoods they called slums. By this point, there was a realization that these neighborhoods often had mostly Black residents.

News outlets, mostly catering to a white audience then, joined in on the effort, publishing a flurry of stories and editorials. One in the Atlanta Constitution was dramatic: in bold letters, among images of low-income homes, it said “Blighted Areas Like These Stab At Atlanta’s Heart.”

An editorial in the Atlanta Constitution, published July 25, 1955, promoted the use of urban renewal to rehabilitate Atlanta’s so-called slums.

But when the city demolished the blocks of rundown shotgun houses and rentals, it created a new challenge. Atlanta had to figure out where all of the displaced people would go.

“The problem is simply this,” Mayor Ivan Allen Jr. said in an address in 1966, recorded by WSB. “Atlanta does not have the housing to meet the needs of persons to be relocated by present or future governmental action which will be necessary for the continued progress of this city.”

Records from Allen’s archives at Georgia Tech show his administration was in a frenzy to build more housing during his last years in office. He initiated low and moderate income developments throughout south and west Atlanta in order to reach his goal of 17,000 new units.

This was when plans for Forest Cove began.

The federal government donated 100 acres of former prison land. The Atlanta Housing Authority chose a developer — an Indiana-based manufactured home builder called National Homes. And in the early ’70s, rows of square townhomes opened off McDonough Boulevard.

Plans for the property that became Forest Cove took shape following the federal government’s donation of nearly 100 acres of former prison land. (Ivan Allen Digital Archive/Georgia Tech)

According to the complex’s first residents, the units were nice. Wilbur Yancy came with his family in 1975 when he was 11 years old. At 58, he still has clear memories.

His family was moving for the first time from an old house they inherited in the Summerhill neighborhood. Inside the townhomes, freshly built with modern amenities, Yancy said he and his siblings were in awe.

“Everything was so clean. It was so new. I wasn’t at that time even familiar with a garbage disposal. I was like, ‘Oh my god. Wow. So we can put stuff in there?’” he said. “So it was just an exciting time for us.”

The name wasn’t Forest Cove then. The sign outside the townhomes said Seasons Four. Residents often changed that to Four Seasons. During this same period, legal documents called the complex Villa Monte Homes.

It started as a housing cooperative for families of mixed incomes. Their rent went toward the mortgage, which the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development subsidized as part of the Section 236 program.

McRae Watson, who moved in as a teenager, remembers the fenced-in patios where his family would barbecue. Hawassia Briley, who joined her mom there as a kid, says the community saw itself as different from public housing, like the Thomasville Heights project across the street.

“It was somewhere you would take your family,” Briley said.

“It was a good place,” Watson said. “It was peaceful and quiet. No drama.”

Wilbur Yancy’s family were among the complex’s first residents. He remembers his early years in the new and clean townhomes as exciting. (Courtesy of Wilbur Yancy)

But according to newspaper archives and court documents, problems were already developing.

In 1976, just a few years after the townhomes opened, the Atlanta Constitution published an investigation with another dramatic headline: “A Housing Dream Shatters.”

Despite the clean new veneer, it said the construction was shoddy. In some units, ceilings were coming apart because of water damage, pipes were bursting in the winter and bathroom sinks were falling out of the walls.

“The list of defects is as long as the rationalizations given by the responsible parties, none of whom accept full blame,” wrote reporter Jim Gray.

The story ultimately placed most of that blame on HUD, which had already supported the developer with $6 million in discounted financing. The agency was supposed to inspect the townhomes before they opened. It didn’t hold National Homes responsible for the deficiencies.

In a statement today, HUD said it couldn’t comment on the allegations. The agency doesn’t retain records from 50 years ago.

In the 70s, though, negligence in the federal agency was widespread, according to Ed Goetz, a professor of urban planning at the University of Minnesota.

HUD was still a new department then, Goetz said. Congress only created the agency, as part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” in 1965. But it was in charge of an expanding portfolio of public housing and also privately-owned publicly-subsidized housing, like Forest Cove.

“There were problems of fraud and abuse in many of the programs that HUD was running,” he said. “So much so that President Nixon essentially called a moratorium on new units in the early 1970s.”

Throughout the decade, local news reported on several federally-funded developments in Atlanta with design defects, ranging from fire safety concerns to serious leaks. One complex in Northwest Atlanta was built so poorly, HUD demolished it after only four years.

Hearing these accounts, an Atlanta area congressman, Elliott Levitas, called for investigations into HUD and the poor construction work. Sitting in his home near Emory University, Levitas, now 91-years-old, remembers his outrage.

“It’s not just the fact that it’s an amazing waste of taxpayer money. It’s not doing what it’s supposed to do,” Levitas said. “But more important than the wasted money is the fact that you’ve got people living under those conditions.”

It wasn’t long before issues appeared at the Forest Cove property, according to an Atlanta Constitution investigation published April 12, 1976.

The congressman’s investigation spanned a couple years. As a result, HUD admitted failures of oversight at every level. According to a 1978 Atlanta Constitution story, then-Secretary Jay Janis told a Congressional Committee that HUD had also implemented a new management system and placed a greater emphasis on audits and investigations.

But a few years later in 1981, Levitas was back on the Congressional floor with a report from HUD’s Office of Inspector General. He said a review of 16 Atlanta properties showed more than 600 undetected construction issues. Levitas concluded then that the abuses were ongoing.

And looking back today, at a much older federal housing agency, Levitas still doesn’t see lasting progress.

“There’s no follow through,” Levitas said. “And unless there’s follow through, there’s no solution.”

“A member of Congress will spot this issue, say, ‘This is terrible. It’s bad for people. It’s bad for the taxpayers.’ And journalists will say, ‘Yeah, you’re right. Look at this,’” he said. “And 30 days later, it’s off the agenda.”

This was true for the Forest Cove property.

In the years after the Atlanta Constitution first published its investigation, the situation didn’t improve. In court records from the early 80s, the cooperative that ran the complex said it was spending so much money fixing defects it couldn’t afford its federal mortgage.

After moving to foreclose, HUD looked for a new owner. When it advertised the sale in the paper in 1983, it estimated the property needed $4 million in repairs. It was barely a decade old.

To rehabilitate the complex, the incoming owner received $4.5 million in tax-exempt bonds from the city’s housing authority. This new company abandoned the cooperative model. The property became fully low-income subsidized housing under the Section 8 program.

From that point, former residents remember the property declining. Four decades later, in which two more owners have bought and sold the apartments, and received at least $21 million more in tax-exempt financing for repairs, attention is on Forest Cove again.

“There’s no follow through. And unless there’s follow through, there’s no solution.”

Former U.S. Rep. Elliott Levitas of Georgia

The new owner, Millennia, has said it hopes to carry out a more than $50 million renovation of Forest Cove using low-cost financing. The city, however, condemned the property in municipal court last December. Millennia’s appeal is now pending in Fulton County Superior Court. For now, the complex continues deteriorating with 200 families waiting for relocation.

Hawassia Briley had moved back to Forest Cove in the early 2000s before leaving again several years ago. “And I feel like the people left over there, they don’t deserve it,” she said. Wilbur Yancy has only driven by. “And it really looked horrible.”

For McCrae Watson, it’s tough to square the level of disrepair with his good memories from when the complex first opened.

“It just went from that to being what it is now, an eyesore,” he said. “You wonder how it got to be that.”

Given the complex’s history, maybe it is no wonder, though.