Atlanta activists, politicians commemorate 60th anniversary of March on Washington

While walking on the grass of Washington, D.C.’s National Mall on Aug. 28, 1963, then-31-year-old Civil Rights leader Andrew Young’s main goal was to ensure that peace remained instilled among marchers and other personnel in attendance.

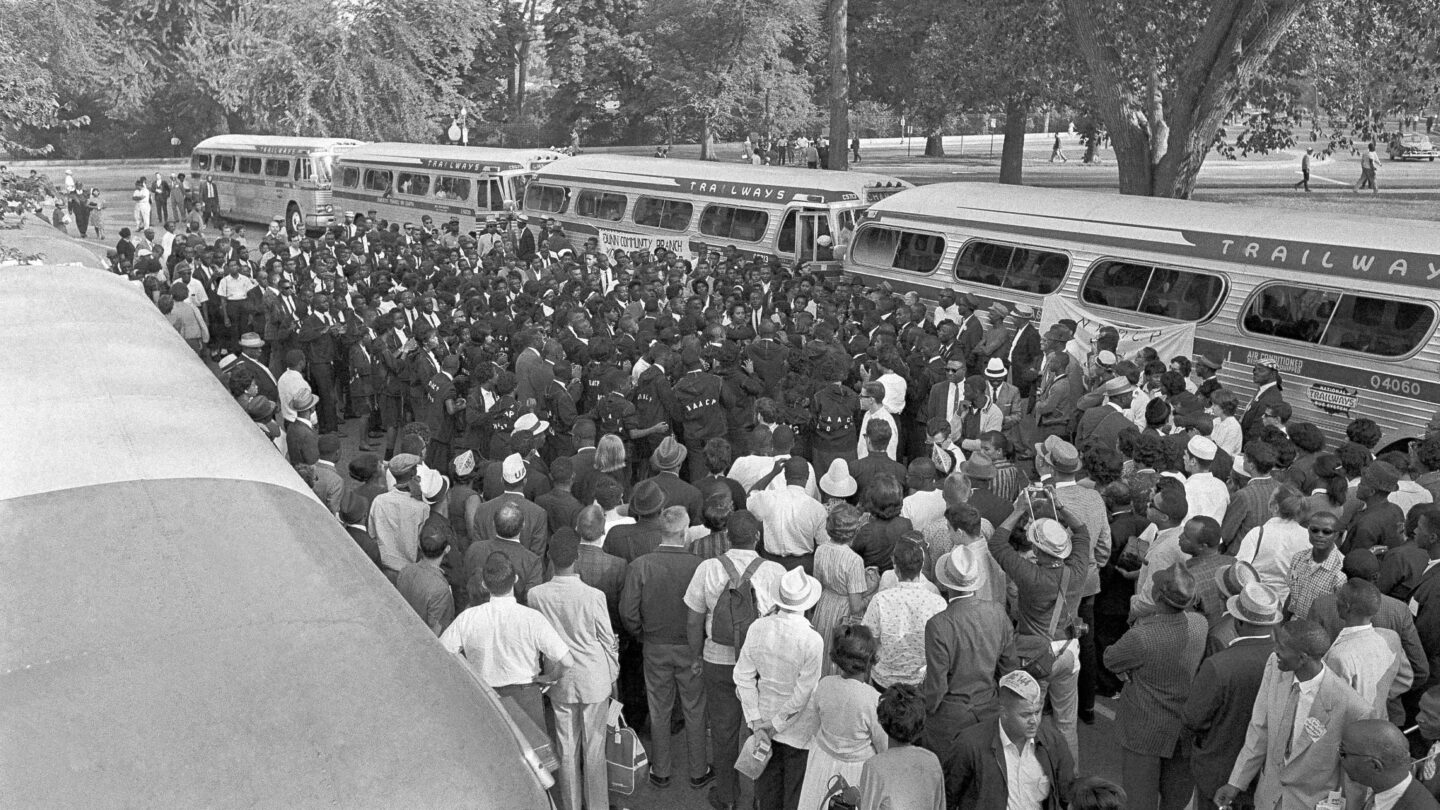

The March on Washington that day 60 years ago was a Civil Rights march that brought hundreds of thousands of Americans to the nation’s capitol to protest racism and advocate for the economic and voting rights of African Americans. It was revolutionary for its time.

For event coordinators in attendance like Young, the march created a feeling of unity and anticipation, but also a fear of violence or the harassment of marchers.

He and his colleagues, including late U.S. Rep. John Lewis, Civil Rights leader Hosea Williams and event speaker Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., quickly discovered that there was no need to panic about the latter occurring.

“It turned out to be very peaceful,” Young, the former Atlanta mayor and U.N. ambassador, told WABE. “The March on Washington really excited the hopes and dreams of everybody … that all men were born with certain inalienable rights; life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

Young was already fighting Civil Rights violations throughout the South in the 1950s and early ’60s when he was first approached to assist with the event. He was surprised by the huge turnout, with an estimated 250,000 marchers of various ages and races in attendance.

“What [Dr. King] would say was … ‘One day the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners would sit down at a table of brotherhood,'” said Young. “The Bible was brought by the Black folks, and [copies] of the Constitution were brought by lawyers.”

While that singular day has been embedded in American history, the historical event was part of a civil and human rights battle that was over 20 years in the making.

Young noted that in the early 1940s, Civil Rights leader A. Philip Randolph — organizer of the 1963 event alongside Bayard Rustin — had originally planned a march for July 1, 1941 in Washington, D.C. to fight for Black laborer rights. However, the march was canceled at the convincing of then-President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

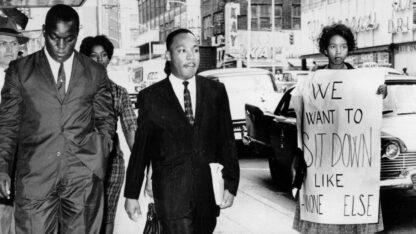

By the early 1960s, a series of Civil Rights protests, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) lunch counter sit-ins, ignited the fuel for the march to move forward, this time with King assisting Randolph and Rustin.

While many attendees were unaware of the impact their resilience would have on future generations, they knew there wasn’t a more urgent time to let the government and the country know of their demands for a better life.

“I can remember being there and being in the mud, and many of the tents were rained out,” said activist and Atlanta native Elisabeth Omilami. “But people still stayed to make a statement that America was not following through on the promises that were due [to] Black people.”

Omilami, daughter of Civil Rights activist Hosea Williams and CEO of the local nonprofit Hosea Helps, said that attending such a historical event as a young girl left a lasting impact on her in the fight for Civil Rights.

“It gave me perspective that we are not just living in a country where we just get money and go home, but that there were things to fight for,” she said. “There were voting rights, there were Civil Rights, there was [an] issue of unpaid wages.”

With a staff of 50 people, Williams, who passed away in 2000, was tasked with responsibilities ranging from setting up food to coordinating medical assistance and awaiting the arrival of marchers, many of whom came by bus, train and some even by horse and wagon.

Julian Bond, the then 23-year-old co-founder of SNCC, was also in attendance and assisting throughout the set-up period.

“So much of America was segregated, not just by where you could sit and eat or go to shop, but also what was on television and on the radio,” said Michael Julian Bond, son of the late activist and an Atlanta City Councilman. “Something such as [the march] had never been seen before … and it took a lot to make it happen.”

The dedication from all of the leaders and coordinators involved paid off, with social leaders, politicians, celebrities and activists nationwide in attendance.

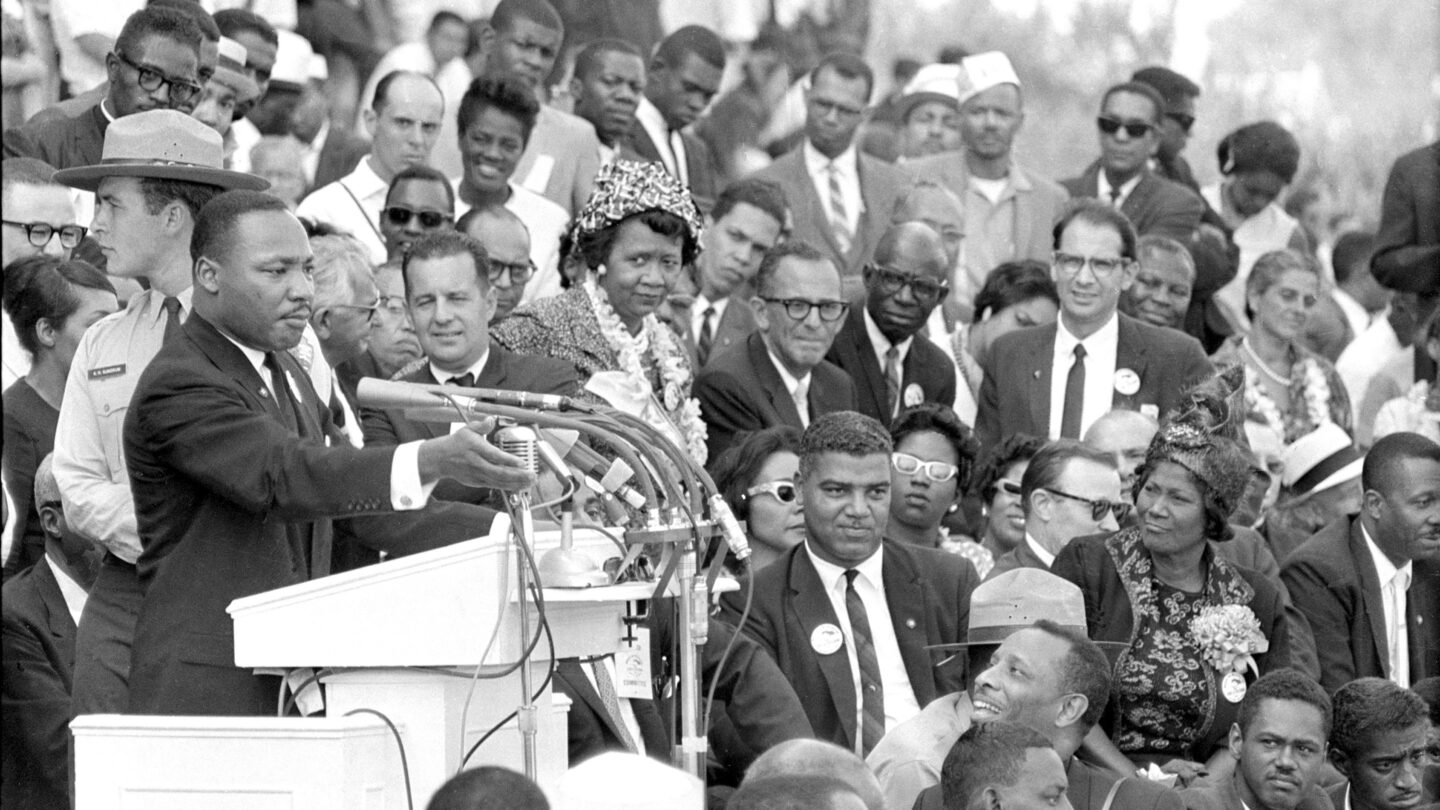

Perhaps the most memorable moment of the event is King’s “I Have a Dream Speech,” where the renowned minister proclaimed, “Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California … [to] Stone Mountain of Georgia.” The speech is still held dearly by generations of Americans.

“The call to action means that is the ‘I Have A Dream Speech,’ from every step we have a responsibility to remain in pursuit [of justice] … to not give in to the harshness of reality,” said politician and voting rights activist Stacey Abrams.

King’s words and the highly publicized event were seen as a gateway to the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and a number of other Civil Rights successes for people of color.

“It led Dr. King to the Nobel Prize. It led us to Selma. It led us to the Voting Rights Act of 1965,” said Young. “It wasn’t just a one-time march… it was a movement of people who wanted to be heard.”

However, Young says that while there has been progress in the past 60 years, there is still a long way to go in the fight for equality.

“As soon as we take two steps forward, someone tries to push us one step back,” he said. “We still have a lot of things to deal with … I can’t go out and celebrate [the march’s anniversary] because there is still so much to be done.”

“If there is one thing that Dr. King encouraged us to do … we have to focus on those who have not and help them to get. Whether it is freedom, whether it is justice, whether is education access, whether it is freedom [from] fear … it is our job to do right and demand access,” said Abrams, whose parents were active in the Civil Rights Movement.

She encouraged young people to follow in the footsteps of activists like her parents and others in the Civil Rights Movement to help put an end to modern-day civil and human rights violations, including voter suppression and bans on race-related books.

“The March on Washington was a call to action and at its center was a demand for jobs, justice and peace. We have the opportunity every day to make that true,” she said.

“We have to participate, we have to call out injustice … we have to protect the human rights we have fought for and we cannot be doubtful,” she added. “If each of us did a small piece of it, whether it’s going to school and reading to children, or showing up to a soup kitchen and making certain someone doesn’t go hungry … [we] can do something somewhere to make a difference. Find your issue, find what animates your heart or what worries your mind, and do one thing each day about it. If we each do that and make that commitment, regardless of age, or station in life or point of entry … we make the world better.”

Despite the strides still to be made, Young takes solace knowing that one factor rings true now just as it did in 1963.

“My human rights are endowed not only by the creator, but also by the Constitution,” he said. “We still have a long way to go, but I think we’re doing just fine.”