Bill to make proving ownership of Georgia marshland less burdensome advanced by state House panel

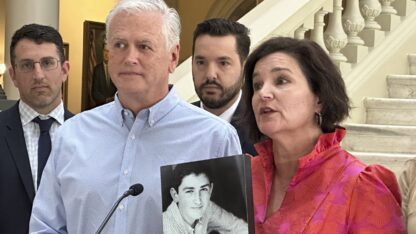

A proposal to reduce the legal burden for proving private ownership of coastal marshlands first granted to Georgia settlers centuries ago was advanced Tuesday by a state House committee.

The House Judiciary Committee voted 6-5 to approve House Bill 370 during a meeting streamed online from the state Capitol in Atlanta, sending it to the full House. Prior versions of the proposal in 2022 and last year failed to get a vote on the House floor.

Conservation groups are opposing the measure, saying it would put thousands of acres of salt marsh currently considered public land at risk of being seized by people who don’t rightly own it.

Rep. Matt Reeves, R-Duluth, and several coastal lawmakers sponsoring the bill say it will encourage restoration of salt marsh that was long ago drained or damaged by farming and other uses.

“For 200 years, these rice farms and other manmade alterations in Georgia’s marshlands have not repaired themselves,” said Reeves, the Judiciary Committee’s vice chair. “Mother nature needs help to restore those marshlands. And this is the vehicle to do it.”

The vast majority of Georgia’s 400,000 acres (161,874 hectares) of coastal marshland is owned by the state and protected from development. State officials estimate about 36,000 acres (14,568 hectares) are privately owned through titles granted by England’s king or Georgia’s post-American Revolution governors during the 1700s and early 1800s.

Critics say the legal process for a landholder to trace ownership to one of these so-called “crown grants” is too cumbersome and can take a decade or longer. The state attorney general’s office handles those cases now and requires evidence of continuous ownership from the original centuries-old grant to the present.

The measure before House lawmakers would establish a streamlined alternative for those who, if granted their claim of ownership, agree to keep their marsh in conservation. Owners would be allowed to sell mitigation credits to private developers looking to offset damage to wetlands elsewhere.

“We’re taking something the state has protected for centuries, and we’re putting it into private hands,” said Megan Desrosiers, president and CEO of the coastal Georgia conservation group One Hundred Miles. “And then that person gets paid to protect something that the state has been protecting for centuries.”

Desrosiers and other opponents say the proposed changes also place an unfair burden on the state to disprove claims of private marsh ownership.

Cases taking the streamlined path would go to the State Properties Commission rather than the attorney general’s office. The commission would have a deadline of nine months to resolve the case. If it takes longer, the person making the claim gets ownership of the marsh.

“The state has an obligation not to give away resources to private citizens,” Kevin Lang, an Athens attorney and opponent of the marshlands bill, told the committee at a Jan. 11 hearing. He said the proposal would “result in people getting title to saltmarsh who never had a valid claim.”

Jerry Williams, whose family was granted marshland along the Ogeechee River in Savannah in the 1800s, told committee members at the prior hearing that state officials have abused the existing process for proving ownership.

“They throw everything at the wall that they can to try to delay, to muddy the waters, and make it cost prohibitive for the private landowners to defend their title,” Williams said.