County Employees Saved Georgia’s Elections, But At What Personal Cost?

The stress of this past election cycle has led some Georgia election employees to resign and some to consider it. However, others are holding steadfast in their positions.

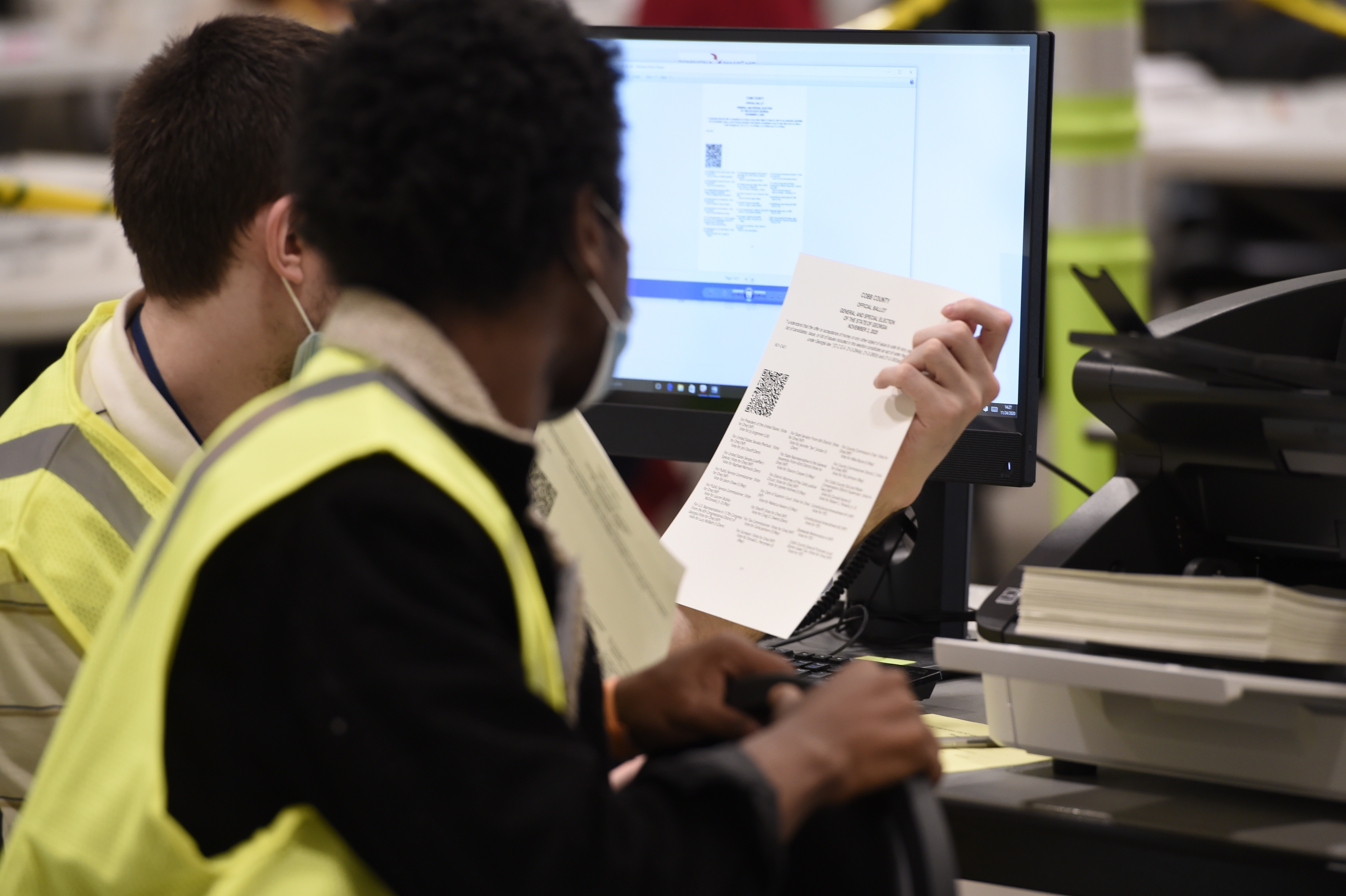

Brynn Anderson / Associated PRess file

This coverage is made possible through Votebeat, a nonpartisan reporting project covering local election integrity and voting access. The article is available for reprint under the terms of Votebeat’s republishing policy.

Deidre Holden has been Paulding County election director for 17 years and has lived in the county since she was 3.

Holden remembers where she was when she first learned the pandemic was going to drastically alter her job.

“I was actually in Nashville, Tennessee, when Secretary [Brad] Raffensperger made the announcement that we were going to postpone the election. And when that happens and you hear that, your wheels start turning on how you can make that work,” Holden said.

County election directors like Holden earned praise for handling the strains of conducting a heated presidential election during a pandemic.

While the stress has led some to resign and others are considering it, some are holding steadfast in their positions.

The government response to the pandemic had an immediate effect on election departments because it meant quickly rescheduling the presidential preference primary originally slated for March 24 of last year.

Like many of her colleagues, Holden had to deal with a drop in poll workers, and older workers who know elections best were the first to go because of their vulnerability to the virus.

It also affected Joseph Kirk and his election staff in Bartow County.

“One of the keys to our success here in Bartow is that we have great poll worker retention. When I took my job in 2007, there was a poll where they were the third generation managing that poll,” Kirk said.

Holden says they got through the challenges of the election by sticking together.

“Our staff, especially my permanent staff, we all agreed we’re in this together, and we’re going to survive through this. We’re going to get through this because it is about those voters and them getting to cast their votes,” Holden said.

‘I Felt Like I Needed To Save The World’

In Athens-Clarke County, elections director Charlotte Sosebee is also a veteran of the department who conducted her first presidential election in 2008, another high-profile year.

“I practically raised my daughter in the elections office because she was a year old when I started working in elections,” Sosebee said.

She remembers the responsibility of trying to protect voters and her staff when the pandemic began.

“Anxiety had kicked in terribly. I spent a lot of days in tears because I felt like this process was put in my hands for me to create something magical to make it safe, and I left like I needed to save the world,” Sosebee said.

Todd Edwards, a legislative director with the Association of County Commissioners, works with county officials to make sure state policies are successfully carried out at the local level. During this past cycle, he said election directors faced a “trifecta” of challenges – losing poll workers and polling places because of the pandemic, new voting machines and the surge in absentee ballots.

Nancy Gay is the election director for Columbia County.

“It was rather interesting because we’d never had that many absentee before. The staffing and personnel to handle the influx of absentee … for the November and January elections, we ended up having to hire 130 temp workers,” Gay said.

On top of that, election departments had the added difficulty of using the Dominion Voting system for the first time. Colquitt County had the benefit of using the machines in a January special election, but most departments had no experience, and much of the training was done virtually.

Wes Lewis is election superintendent for Colquitt County near the Florida border.

“Even though it was only a small part of our county, we were able to get a jump start with the new Dominion system,” Lewis said.

Confusion over how the Dominion machines work led to many questions for county election departments, which Lewis and others say could be answered if people became more involved in the process.

“We would love for people to show up when we test the equipment; we would love for people to come and watch us when we’re opening or closing. That’s their right to do it,” Lewis said.

Election Day Arrives

And although Election Day itself in November went smoothly in most parts of Georgia, the following several weeks were challenging.

Election departments had to perform a hand audit of millions of ballots and a machine recount as they were preparing for another high turnout race in January, all while receiving national media attention.

“I think what’s of most concern is the amount of scrutiny that election workers have come under. It doesn’t seem that either side of the political aisle is pleased with elections following the new voting machines – and these are legitimate concerns – over voter suppression on one side or voter fraud on the other,” Edwards said.

While most counties experienced higher than usual engagement from the public, some counties also had to contend with outright harassment and threats.

Kirk still has the bomb threat checklist within arm’s reach on his desk. Holden recalls the threat they faced in Paulding County.

“We were really happy that we didn’t have that going on here, and then the weekend before the election we were one of the eight counties that got the threatening email. You want to think that’s just somebody trying to create turmoil, but you don’t know, and you have to take everything like that very seriously,” Kirk said.

Still dealing with the aftermath of November, counties had another election to run – the critical January U.S. Senate runoffs. Kirk says he is still recovering from the stress of this past election cycle.

“I don’t think I realized the toll it took on me until after it was over when I went home and started relaxing and was waking up in blind panics every morning thinking about work when there was nothing to think about,” Kirk said.

Moving Beyond 2020

Todd Edwards is now working with lawmakers as they draft new voting laws that will affect the way counties conduct elections.

He said the 2020 election cycle put an immense amount of pressure on election workers.

“All eyes seem to be focused on how elections are handled and poll workers,” Edwards said. “And when you have this close of elections and that amount of scrutiny, that amount of pressure, every move ending up on the news, people’s names being mentioned … frankly, I don’t know why you would want to be a poll worker in this day and age, and I commend the folks that volunteer to serve and be employed in this capacity.”

Kirk, for his part, says he has no intention of leaving the position.

“I’m crazy enough to love my job, and I plan to continue to do what I do, but it’s going to take a toll on us as a state, and we’re going to lose a lot of institutional knowledge because of people’s anger,” Kirk said.

Others, like Charlotte Sosebee, say they have at least considered leaving but plan to remain for now.

“During the process, I was like, OK I think I want to go back to banking because I was in banking before I got into elections. Then I was like, maybe I’ll go over to landfill, work where they sort recycling … I cut up like that, but I’ve been doing this so long, it’s my life. I don’t know any other thing I’d rather be doing,” Sosebee said.

While lawmakers at the Georgia Capitol debate what role absentee voting will play in elections going forward, Sosebee says she feels prepared to continue to handle absentee voting on a large scale and is already preparing for 2022.

“My opinion, I think now that we’ve done it, we could continue doing it because we developed some kind of expertise in it,” Sosebee said.

Milton Kidd, election director for Douglas County, believes he is not alone in considering a career change.

“I think myself and election workers across the state are reconsidering being in these positions. It’s like this — when you wake up every day and you’re trying to do your job to the best of your ability and, some anonymous some not-so-anonymous, are making false accusations against you, that takes a toll on you,” Kidd said. “I think there are going to be a wave of election directors that retire in this next year, and that have retired, simply because of the stress and burdens that are being put on these civil servants.”

Amber McReynolds is with National Vote at Home institute, a nonpartisan group that works with states to expand mail-in balloting. She says she personally saw more turnover after last year than in previous years.

“We often see some after a presidential election, I will say, but I do think 2020 was particularly hard for people who work in elections,” McReynolds said.

Fayette County currently has a job posting out for elections director. Their previous director resigned following the November election, when a batch of uncounted votes was found after certification. Newton County is also searching for a new elections director.