Freaknik attendees remember legendary spring break festival before upcoming Hulu documentary premiere

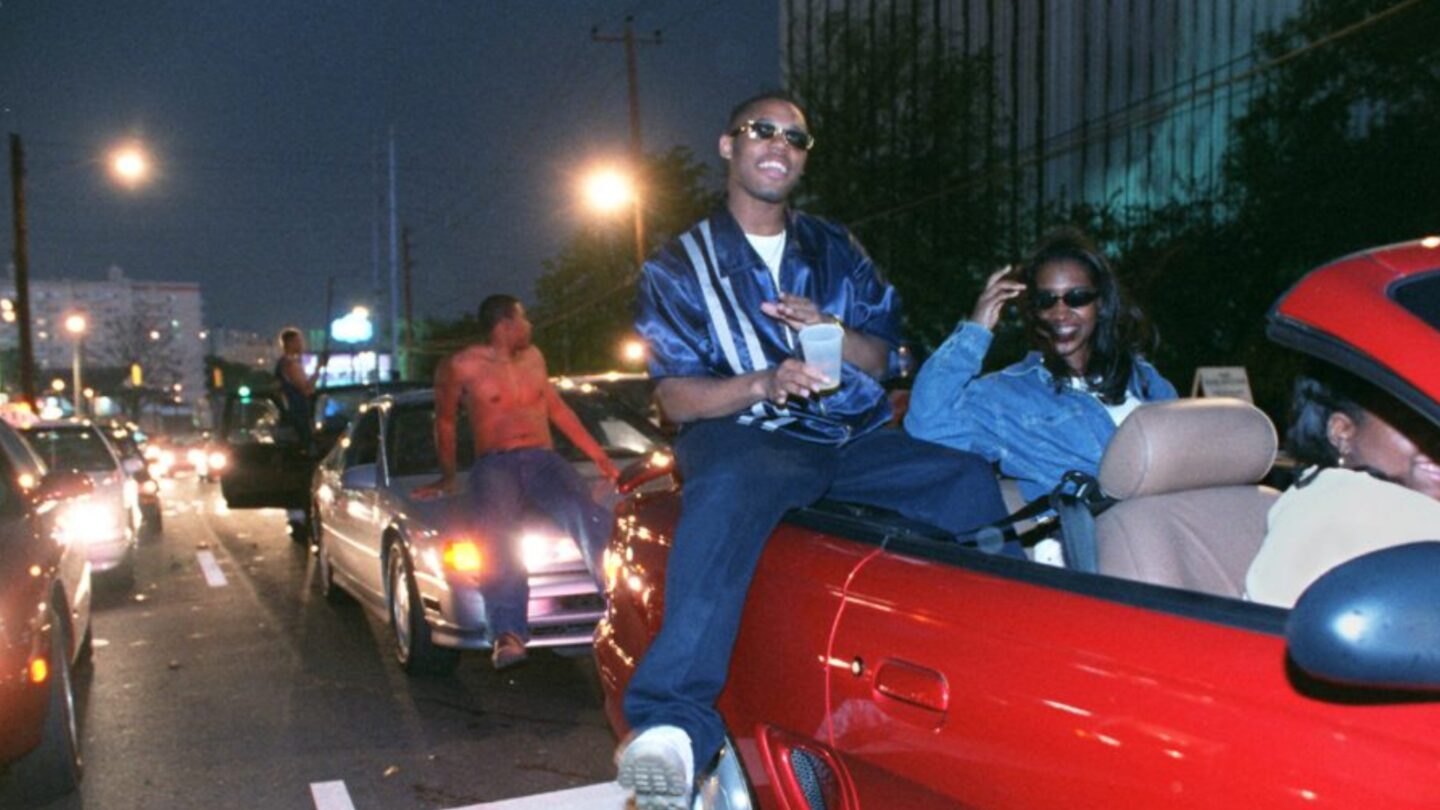

Beginning in the late ’80s and lasting throughout the ’90s, Freaknik was an annual celebration created by students at Atlanta’s historically Black colleges and universities. The days-long festivities — centered around Black expression — quickly became a cultural phenomenon.

The now legendary Atlanta festival is the main focus behind the upcoming Hulu documentary, “Freaknik: The Wildest Party Never Told,” which premieres on the streaming service on Thursday, March 21, and is executive produced by Atlanta residents, music producer Jermaine Dupri and rapper 21 Savage.

Despite it being nearly 25 years since the last official Freaknik celebration in 1999, those who experienced the event in its heyday still have fond memories of the festivities as if it had occurred yesterday.

Tarangela Jones, a resident of Atlanta’s Hunter Hills community, was in her early 20s when she first attended the festival.

“It was parties everywhere … you had cars just cut off the whole street,” said Jones. “Everybody bumping their music in their cars, all the girls in their booty shorts!”

At its height, over 250,000 Black partygoers from across the country took over Atlanta’s streets. Despite the crowdedness of the event, Jones remembers everyone in attendance just wanting to have fun.

And in the age of the golden era of hip-hop and bass music in Atlanta, it was not a difficult feat to find a popular club or dance spot to frequent throughout the festival.

Cedric Middlebrooks, a 54-year-old “Grady baby”, was a young high school graduate when he first attended Freaknik in it’s heyday.

Now a chef, he grills hotdogs and tosses fresh fries in seasoning, recalling riding around the city in his Drop-top lowrider.

“It wasn’t no fighting, no fussing, no cussing — just dancing and having a good time,” said Middlebrooks. “You had women, men … everybody was [having fun] in the streets.”

That is not to say that the event did not have its share of difficulties.

Kenley Waller, a soul food restaurant owner in Atlanta, remembers the challenges for businesses at the time. During the festival’s popularity, he ran a Shoney’s on Wesley Chapel Road, noting that the all-you-can-eat restaurant required 24-hour security.

“It was unbelievable, it was so many people,” Waller said. “It was, like chaotic. But, we made a lot of money during that period of time, but we also lost a lot of money.”

Eventually, traffic and safety concerns… among others… led to the end of Freaknik — and the end of an era.