Ga. Anti-Abortion Pregnancy Centers Look At New State Funds

Kasey Burroughs can still remember sitting in the parking lot at PRC Medical Clinic a few years ago. There was a lot on her mind.

Burroughs says everyone she knew didn’t want her to be pregnant. She was alone, and trying to decide her next move. Keep the baby? Adoption? Abortion? The last option brought up painful memories.

“Back in high school, I had my first abortion,” Burroughs said. “My mom took me to an abortion clinic and I had an abortion. I had no choice whether I wanted to keep it or not. It was her decision.”

Back then, she was 17 years old. Still in high school. But now years later, the decision was up to her.

“And I actually had Googled it – ‘abortion clinic’ in Atlanta or Douglasville or just ‘abortion clinic’ – I don’t remember exactly,” she said. “And this clinic was the first thing to pop up.”

PRC Medical’s website is “abortiondecision.com.”

Pregnancy Resource Centers

“We have a good online presence. You’ve seen our website. That’s the way most kids find us,” said Judy Davis, who founded this center. These facilities are sometimes called “crisis pregnancy centers.” More recently, their supporters prefer “pregnancy resource centers.”

They are organizations that may provide ultrasounds or other services for pregnant people while discouraging them from getting abortions. Last week, Gov. Nathan Deal signed a bill that will now allow the state to subsidize these centers with state grant money.

“We’re open like 44 hours a week. And we do offer not only pregnancy testing, but limited ultrasound,” said Davis. “We also also offer STD testing and treatment, we offer sports physicals for females.”

They conduct parenting classes where people can earn diapers, clothes or other baby supplies. Davis said she makes sure her staff and volunteers are trained not to judge the people who walk in.

“We want somebody who is going to be led by the love of the Lord, not to preach, not to shame, not to tell somebody what to do, but just to love them to let them know that they’re accepted, they’re cared for,” she said. “Just like all the rest of us, when we feel that, we feel safe. This has got to be a safe place.”

This center sees up to 250 new clients every month. Davis says the typical client is about 17 years old. Most of them come in looking for free pregnancy tests, but counseling and providing information are a big priority, according to executive director Sally Buckner.

“Everything we do here is educational,” she said.

Informational Accuracy

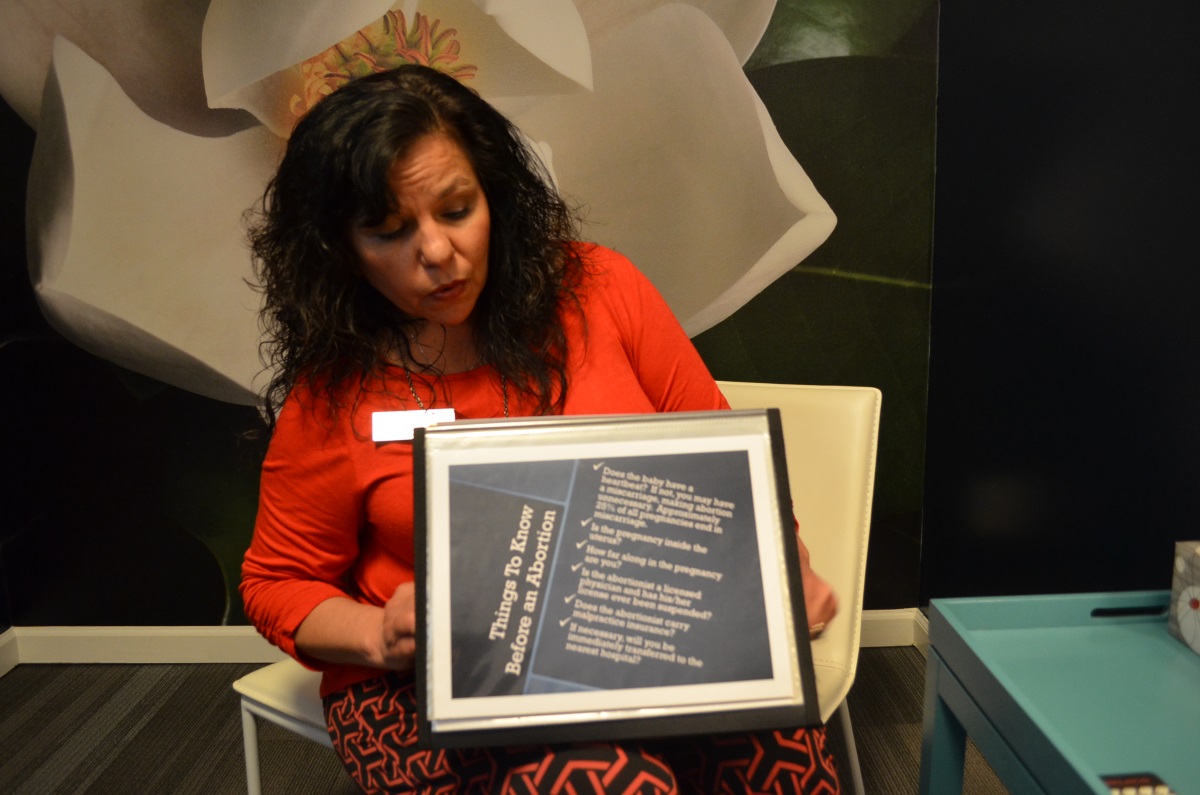

“This is information on abortion, abortion risk,” said Buckner, thumbing through some of their teaching materials on a flip-board, which read: “Bleeding, infection, cervical injuries, perforation of uterus, infertility due to scarring, damage to nearby internal organs and rarely, death.”

Asked how accurate the information is, she responded, “Those are risks that have happened, yes.”

Dr. Amy Bryant is an OBGYN and professor at University of North Carolina.

“The major risks associated with abortion are extremely small so the risk of death is well under what the risk of what they would be if you carried a pregnancy to term and had that baby,” Bryant said.

Explaining risk – putting it in the right context for each individual case – is key to good medical care, she said. Bryant is one of a team of researchers who have studied the information used by crisis pregnancy centers, including those in Georgia.

They have consistently found that the centers use “inaccurate and misleading” information.

These concerns came up when the bill was being debated by Georgia lawmakers. Some tried to add amendments that would regulate the way the centers advertise. The bill’s sponsor, Sen. Renee Unterman, successfully resisted those attempts.

“I’m not concerned about a billboard with false advertisement,” Unterman said. “I’m worried about a woman who goes to an abortion clinic and comes out with a severe infection or who never comes out, because they die because of the procedures that were done in a clinic that is not heavily regulated. That would be my concern.”

For her, and many others, strong emotions can be a guide during debates over women’s reproductive health, and especially about abortion.

“There are literally thousands of mothers and fathers out there who wanted to have a baby. I laid on my pillow when I was 18 years old and cried every morning knowing I couldn’t have a family. It was only God’s intervention, God’s blessing that he put two beautiful live births in my life,” said Unterman, who said that these potential mothers and fathers hope and pray women will call into pregnancy centers, giving them the chance to be parents.

Back at the center, Kasey Burroughs said there’s no doubt things can be tough with four kids, but she has no regrets about having her daughter. She said her mind was made up when she saw the ultrasound that day in the center.

”It’s no trick, it’s no plot or scheme,” she said. “They don’t scream ‘Jesus, Jesus, Jesus.’ It’s just pure love.”

But, she said, it’s not just about love.

“I didn’t have insurance,” she said. “So coming here and knowing that I didn’t need to have insurance to get the help that I needed, that was great.”

Women’s Health

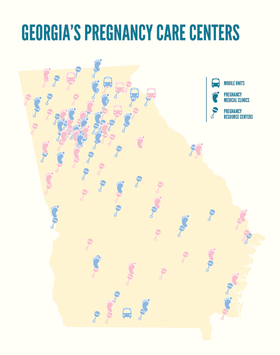

Now with state money available for Georgia’s crisis pregnancy centers, expansion is definitely part of the plan.

Alison Thornton is a nurse practitioner at the center Kasey Burroughs came to. She’s aware that centers like the one she works at face criticism, but she says the women and girls that come in the door need help that they may not find elsewhere.

“Medically they really haven’t seen a provider usually on their own outside of their family doctor when they were in pediatrics,” Thornton said.

She already performs free sports screenings for school aged girls. With more funding, she’s hoping they can afford to hire a second nurse, start programs aimed at childhood obesity or serve more undocumented immigrants.

This year $2 million of state funding will be available for more than 70 centers. It may not be much to go around; in other states that offer funding, that amount has risen over time. Thornton said it’s a beautiful situation that lawmakers want to help the centers operate on an even larger scale.