Georgia Conservation Announcements Add Up To A ‘Pretty Exceptional Month’ For Land Protection

The hairy rattleweed grows in only two counties in Georgia, and nowhere else.

Carol and Hugh Nourse

A large coastal property in Georgia, zoned for commercial development and tens of thousands of homes, could become a Georgia wildlife area instead. The Ceylon property is one of the largest pieces of undeveloped land on the Georgia coast, and if it’s permanently protected, it will help the state work toward some major conservation priorities.

The Ceylon tract is about 25 square miles of forest, streams and saltwater marsh on the mainland, near Cumberland Island.

“It’s a fantastic example of coastal habitats,” said Jason Lee, program manager with the wildlife conservation section at the Georgia Department of Natural Resources.

Before the Civil War, the property was a cotton plantation, Lee said. Then it was used for timber and managed by the Sea Island Company for deer and quail hunting. Then, it looked like it might get developed.

“This property is zoned to be able to take over 20,000 single-family homes, high density,” said Andrew Schock, Georgia State Director for the Conservation Fund. “Three million square feet of commercial space and up to two deepwater marinas all were possible on this site.”

Instead, the Conservation Fund and the Open Space Institute bought the land.

The Ceylon tract is potentially a big deal for the state’s work to protect gopher tortoises, big, wrinkly animals that Georgia is hoping to keep off the endangered species list through the efforts of a coalition of agencies, businesses and organizations called the Gopher Tortoise Initiative.

Lee said they’ve counted thousands of gopher tortoises on the Ceylon property, “a huge, huge population,” he said, “possibly the biggest in the state.”

There is longleaf pine forest on the land, and areas where longleaf could be restored. The longleaf pine ecosystem used to cover tens of millions of acres of land in the Southeast; now there’s just a small fraction of it left.

The big chunk of land also helps with responding to climate change.

“It’s sort of part of what you could call a coastal defense strategy,” said Maria Whitehead, senior program manager for the Open Space Institute.

Because the property goes from the marsh up into the woods as sea level rises, the marsh will have room to move up and back, too.

“In an alternate scenario where we have homes right on the edge of marsh, that migration space is not there,” she said.

The state of Georgia plans to buy the property from the two conservation groups eventually, and, beginning next year, the land could start being opened up to the public.

The announcement that the Ceylon property had been bought by the groups came just a few days before another Georgia land protection announcement: the state has purchased a couple of other smaller South Georgia properties from the timber company Rayonier.

One will be another piece of the Altamaha River corridor, a long-running project to protect land along Georgia’s biggest river.

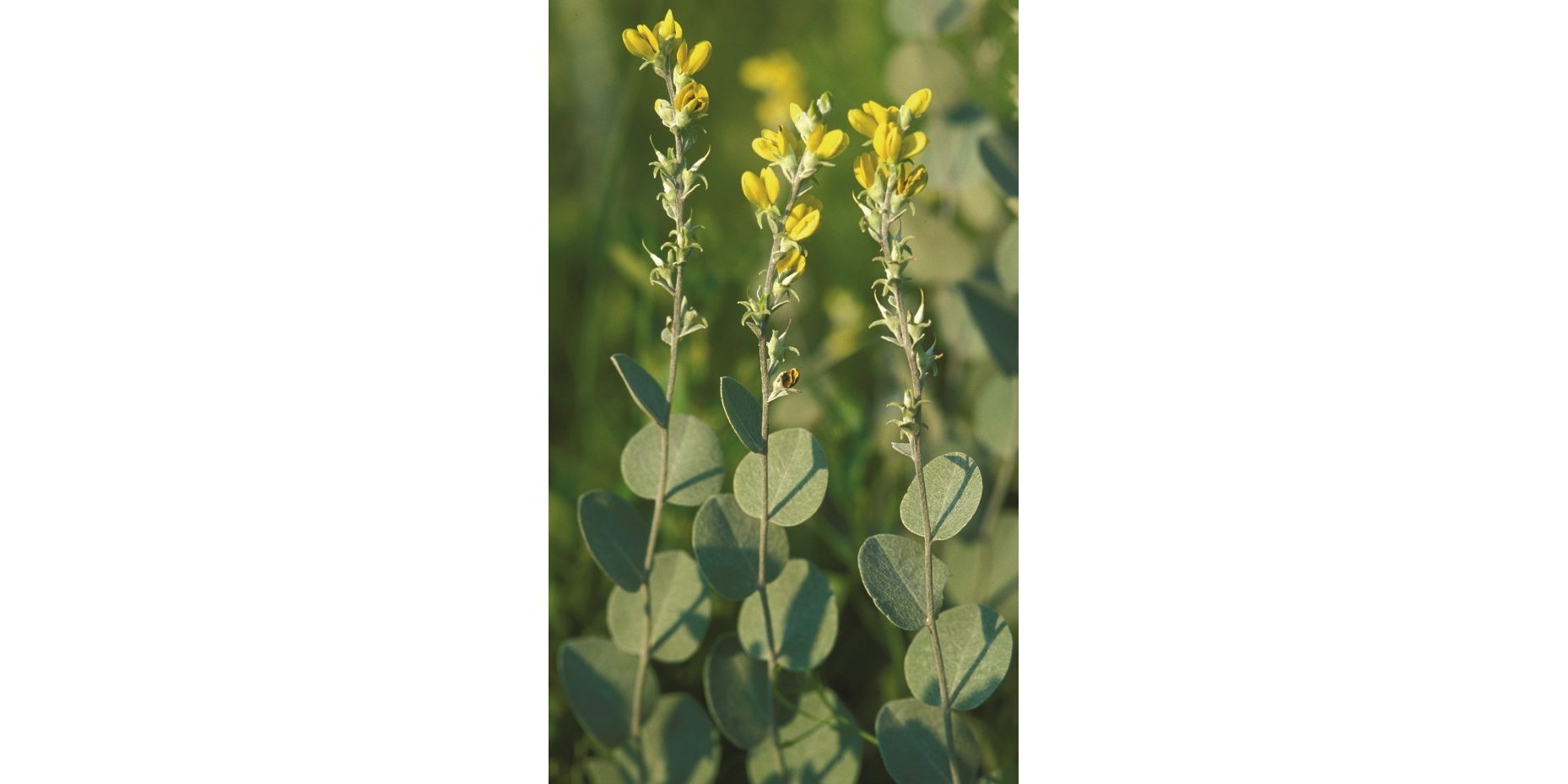

The other protects the biggest known population of an endangered plant. The hairy rattleweed, a yellow-flowered pea relative, grows only in Georgia, and here, only in two counties.

Jacob Thompson, a biologist at the state Department of Natural Resources, said it was great to find property with such good conditions for the rare plant. Thompson first began working on the plant in grad school.

“To see this large population get protected is really incredible,” he said. “It’s a neat looking plant and adds to the beauty of the ecosystem and to our state.”

The state bought the Rayonier properties with help from the Open Space Institute, U.S. Fish and Wildlife and the Knobloch Family Foundation.

The announcements add up to about 18,000 acres of land. Whitehead said it’s not unusual to have more closings toward the end of the year, but the size of the Ceylon tract alone makes this bunch unusual.

“This was this was a pretty exceptional month for land protection in Georgia,” she said.