Georgia Grants Approval To Spaceport Camden, Clearing Path To License

The Georgia Department of Natural Resources has given its approval to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) for a proposed spaceport on Georgia’s coast.

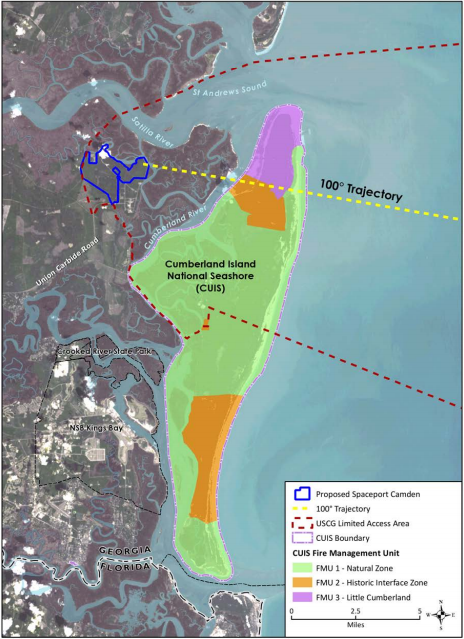

It’s a milestone in Camden County’s quest towards a commercial spaceport that has been plagued by opposition from environmental groups and owners of property on Little Cumberland Island, which lies beneath the proposed rocket trajectories. More than 3,000 county residents have signed a petition to force a referendum on the project, which county officials have pushed as an economic development opportunity.

After nearly a decade since Camden first began contemplating a spaceport, the FAA is expected to decide this month whether to grant the county spaceport operator license. (All actual rocket launches would require additional licenses from the agency.)

‘This is not a tool to stop it’

The role of the state in the process has been to evaluate whether the proposal violates any of Georgia’s environmental laws, since about 2,700 acres of the proposed rocket debris field is state-owned marsh and waters. And, according to Doug Haymans, director of the Coastal Resources Division of the Department of Natural Resources, “We don’t find the mechanisms within current state law to object to Camden County’s federal consistency concurrence.”

Georgia laws “don’t contemplate rocket launches,” he said.

“They’re there to protect the estuary, the marshes, our soils, air, water, but there’s nothing in Georgia law at the moment that regulates rocket launches.”

The department received more than 1,700 public comments about the project; many of the comments were form letters, but almost all were in opposition to the project.

Haymans said there has been a misunderstanding among some members of the public about the state’s ability to stop the spaceport.

“This is not a tool to stop it,” he said of the state’s role. “This is a tool to make sure that as much as possible they adhere to Georgia state law. And if at any point they look like there’s a violation of state law, we point that out.”

The news comes after the FAA released a favorable Final Environmental Impact Statement on the proposal last month.

“Now that the coastal consistency determination and the [Final Environmental Impact Statement] have been released and are favorable to the issuance of a license, we await final determination from the FAA,” said Camden County administrator Steve Howard.

“If a license is issued, we believe we will be highly competitive with other facilities on the East Coast,” he said.

Camden County hired two former staffers of Gov. Brian Kemp for government affairs work related to the project earlier this year. However, Haymans said that outside of the comment letters, they have had no contact with lobbyists. The governor’s office did review the letter, he said, and made minor changes

‘Inconceivable’

Some of the spaceport’s opponents were dismayed by the state’s decision.

“It is inconceivable that you need a permit under the [Coastal Marshlands Protection] Act to install a dock but not to fill the marsh with rocket debris and chemicals,” said Kevin Lang, vice president of the Little Cumberland Homeowners Association.

Brian Gist, an attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center said the state’s decision “illustrates how disjointed and incomplete the environmental review of this project has become. The fact that basic information—like the expected failure rate of the rockets it plans to launch—remains unknown at this stage of the process demonstrates how comprehensively the Federal Aviation Administration has failed to properly evaluate this project.”

Haymans said that over the past six months, the state has used the “tool” it has had available to protect the state’s resources: negotiating with the county. The state was able to secure several new commitments from Camden, he said.

One addition he highlighted is a maximum of 114 hours of closures of waterways per year, over no more than 24 days.

“We’ve heard and talked with so many other spaceports around that [say], ‘Yeah, [rocket companies] say they’re going to close for three hours, and then they’re closed for 18, day after day after day,’” said Kelie Moore, the Coastal Resources Division’s federal consistency coordinator. “We’re ensuring that is not going to happen.”

“We are very conscious of those exclusions of public use, and we were very diligent in trying to minimize them,” she said.

There’s also a minimum insurance coverage now required of rocket launch companies by the state to cover environmental cleanup costs, out to three nautical miles in case of a “catastrophic failure.”

But ultimately, Haymans and Moore said it’s the federal government’s role to ensure the safety of those rocket launches.

“We can’t really regulate on probability,” Moore said. “An airplane might crash into the marsh. We’ve had that happen a few times before. But we don’t make airports get permits for something that might happen.”

Following this approval from the state, one final barrier to the project’s license could lie with the National Park Service.

The project’s proposed rocket launch trajectory flies over Cumberland Island National Seashore, which is managed by the Park Service. The Park Service has been a “consulting party” on the project’s environmental review but has consistently raised questions about its effects on the park.

In a June 2021 comment letter, Gary Ingram, Cumberland’s superintendent said that “numerous aspects of this process…continue to cause concern.”

The Park Service’s questions regarding how a spaceport would affect the park’s resources and the safety of its visitors have gone unanswered, he said.

As outlined in the Final Environmental Impact Statement released last month, the county proposes “land and water security control checkpoints to “control and monitor public access around the launch site” during launches, to include parts of the National Seashore.

For example, he asked, “what is the potential for effects to historic properties from a catastrophic failure/fire?”

“If the FAA is unable to address these questions, then we strongly suggest that the process should not move forward until such time as answers can be provided,” Ingram said.