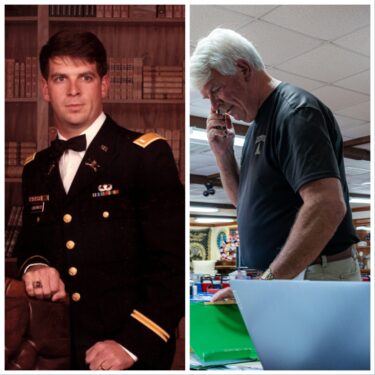

The weeks leading up to Veterans Day are often a crucial time for American Legion Post 45 service officer Jim Lindenmayer.

On a weekday morning at the Legion’s Canton location, the retired Army captain actively returns phone calls, oversees operations throughout the facility and examines plans for an upcoming barbecue to honor the city’s service members.

It is a position that his time in service has made him more than equipped to operate.

“I was a troop commander. I had 175 guys working for me,” said Lindemayer. “You learn management, you learn how to get things going … we made decisions every day … there is no ‘I tried my best it didn’t happen,’ you do.”

The Legion, a national organization comprised mainly of Korean, Vietnam and Gulf War-era vets, is wired to assist those in local regions across Georgia.

“[We are] trying to improve the image of the veteran so that they feel comfortable asking for help,” The West Point graduate said. “And a lot of them do need help.”

Lindenmayer, who also serves as the director of the Cherokee County Homeless Veteran Program, shares the honor of serving in the U.S. military with over 600,000 other Georgia residents, whose tours of duty range from The Korean War in 1952 to Afghanistan in 2012.

It’s a bond that could be seen in full display at East Cobb Park on an early November afternoon, where veterans of all ages and branches walked through the grass eating hot dogs and chips, listening to live music and engaging with each other like old friends, despite many attendees meeting for the first time that day.

“The comradery and being part of a team is huge [for veterans],” said Kim Scofi, president and CEO of United Military Care, the event’s coordinators and Marietta-based nonprofit that provides veterans with resources ranging from housing to career training.

Jacqueline Williams, who served in the U.S. Army for 14 years, agrees.

“The military is very family-oriented,” said Williams. “You never want for anything … you are so close that you have to look out for each other.”

Away from her own children when serving overseas in the early 1980s, she notes that while the separation was difficult, being overseas was adventurous and often indescribable for those who have not experienced it firsthand.

“There are some stories that you can’t even tell to civilians because they will only assume that you are making it up,” said metro Atlanta resident and retired Marine Robert “Moon” Mullins.

An hour away from the UMC festivities at his Southwest Atlanta home, Mullins, who served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1954-1984, recognizes his time overseas as one of resilience, brotherhood and perseverance.

The walls of his study are decorated with commemorations of his time in the military, each with a story to tell.

When pointing out a portrait of himself in uniform, he reminisces on being only 16 when he initially joined the service to escape his father’s strict household.

“The [recruiter] told me, if you want to join the Marine Corps, all you have to do is sign these papers … this is a Thursday. Then I left out of there [for basic training] on Tuesday.”

While serving in Vietnam, Mullins was separated from a wife and child back home in Philadelphia but quickly rose in the ranks — a difficult feat at the time.

“There was an animosity about Black folks,” said Mullins. “Not everyone liked it. There was always a lot of tension between the Black Marines and the white Marines.”

But despite this, Mullins says, the Marines were united and determined when it came time to fight. One crucial mission he experienced proved the importance of the bond between soldiers, regardless of race.

“My last combat mission, we caught an extraction,” he said. “We would come out and go back to the unit; there were 89 holes in my helicopter. [I wondered], ‘How did it not hit me?’… but it didn’t.”

Even when combat is done overseas, many soldiers still experience various battles when they return home to their loved ones and civilian life.

“There is a lack of education when we talk about veterans being taught how to readjust to civilian life,” said Scofi. “[When service members enlist], most of the time, you’re just out of high school or college … you don’t have a lot of life experience, and someone’s breaking down your ideals or your beliefs, and building you up to be something else, and they send you to war or to a desk or wherever else … you go and you do your job and its time to get out of the military.”

“We put them out there into the world and say ‘go make a difference,’ all the while, they still haven’t come to an understanding of what they even dealt with, whether it was moral, whether it was a physical injury,” she added. “They aren’t even able to absorb that.”

Feelings of isolation and loneliness can also contribute to many veterans facing battles with addiction, depression and suicide after they return home.

“In the civilian world, you don’t have a lot of people that you can depend on,” said Williams. “To get out of [the military] … and come back to [an environment] where you couldn’t really depend on your next-door neighbor or your family … it was hard.”

Lindenmayer notes that while many soldiers and civilians were not aware of post-traumatic stress disorder or other mental and emotional health disorders during their time in service, there has been a significant rise in awareness as to how these struggles affect those in service.

However, the willingness of soldiers to reach out for assistance has not rapidly increased.

“Veterans, especially Marines, don’t want to tell people they can’t take care of themselves … if we can get these guys to get help, seek help and at the same time help their families, that’s what we want,” said Lindenmayer.

Another factor that is often difficult for veterans to combat is financial insecurity, particularly when there is difficulty maintaining stable work due to physical, mental or behavioral disabilities.

This leads many former soldiers and their families to live without adequate housing, food and medical resources.

There are more than 600 homeless veterans documented in the metro Atlanta area, and out of the 750,000 veterans living in Georgia, according to Lindemayer, 40% are living in poverty.

To combat this epidemic, Scofi and her UMC staff have developed initiatives in their respective organizations that provide those in need with career assistance, transportation, shelter and meal packaging.

“The least we can do — the least we can do — is give them the tools, opportunity and support after they have given so much for us,” said Scofi, who expects to see a rise of veterans at UMC this upcoming holiday season due to colder temperatures and high emotional turns.

“When you can’t be around your family, and you don’t have family with you or supporting you, we see a psychological downfall. We try to do what we can to show that we love them and that we care for them,” she added.

Despite the trials and tribulations of serving, all these veterans say they have no regrets about their time in the armed forces.

Williams and Mullins both encourage young people interested in serving to build a career in the military.

“Let me tell you something, I have no idea what I would have become if I had not joined the Marines,” said Mullins. “I will tell any young man or young woman who wants to have a viable future, to travel the world, get paid for what you do and go to school — the military is the place to be.”

“It is what you make it,” said Williams. “If you think you’re going to talk back, don’t go. If you think that you’re not going to follow orders, don’t go. All my kids went in, my grandson went in…[it gave them] role models. But, it’s not for everybody.”

As far as what civilians and government officials can do to support veterans and those actively serving, Lindenmayer believes that Georgia still has a long way to go.

“We want to be counted. We stood up to protect this country — that is what our number one job was. Spending long hours, missing holidays, birthdays, anniversaries to do what we thought was right for the country,” he said.

“We’re not asking to be thanked for [service] — we want to make sure that the systems that are supposed to be set up to take care of us are there. And unfortunately, they’re not.”

Veteran Resources

Local and State Resources

Georgia Department of Veterans Services

National Resources

Defense Finance and Accounting Service (DFAS)

Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency

Employer Support for Guard and Reserve (ESGR)

Request Military Medical Records

Request Veterans Service Records (DD214 & SF180)

Social Security Administration

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA)

VA – Ask VA

VA – Crisis Line

VA – DOD eBenefits

VA – Forms

VA – Health Care

VA – Survivor Benefits

VA – Veterans Benefits Administration

VA – Vocational Rehabilitation & Employment (Vet Success)

USDOL Veterans’ Employment and Training Service (VETS)

Yellow Ribbon Reintegration Program

Women Veterans

VA – Center for Women Veterans

Minority Veterans

VA – Center for Minority Veterans

Homeless Veterans

Homeless Assistance Resources in Georgia

Homelessness Resource Exchange

National Coalition for Homeless Veterans

U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness