Georgia Voting: What The ‘Dedication Of Fees’ Ballot Question Means

A “yes” vote is a vote to allow Georgia lawmakers to dedicate money from fees to the funds that the fees are supposed to be for in the first place.

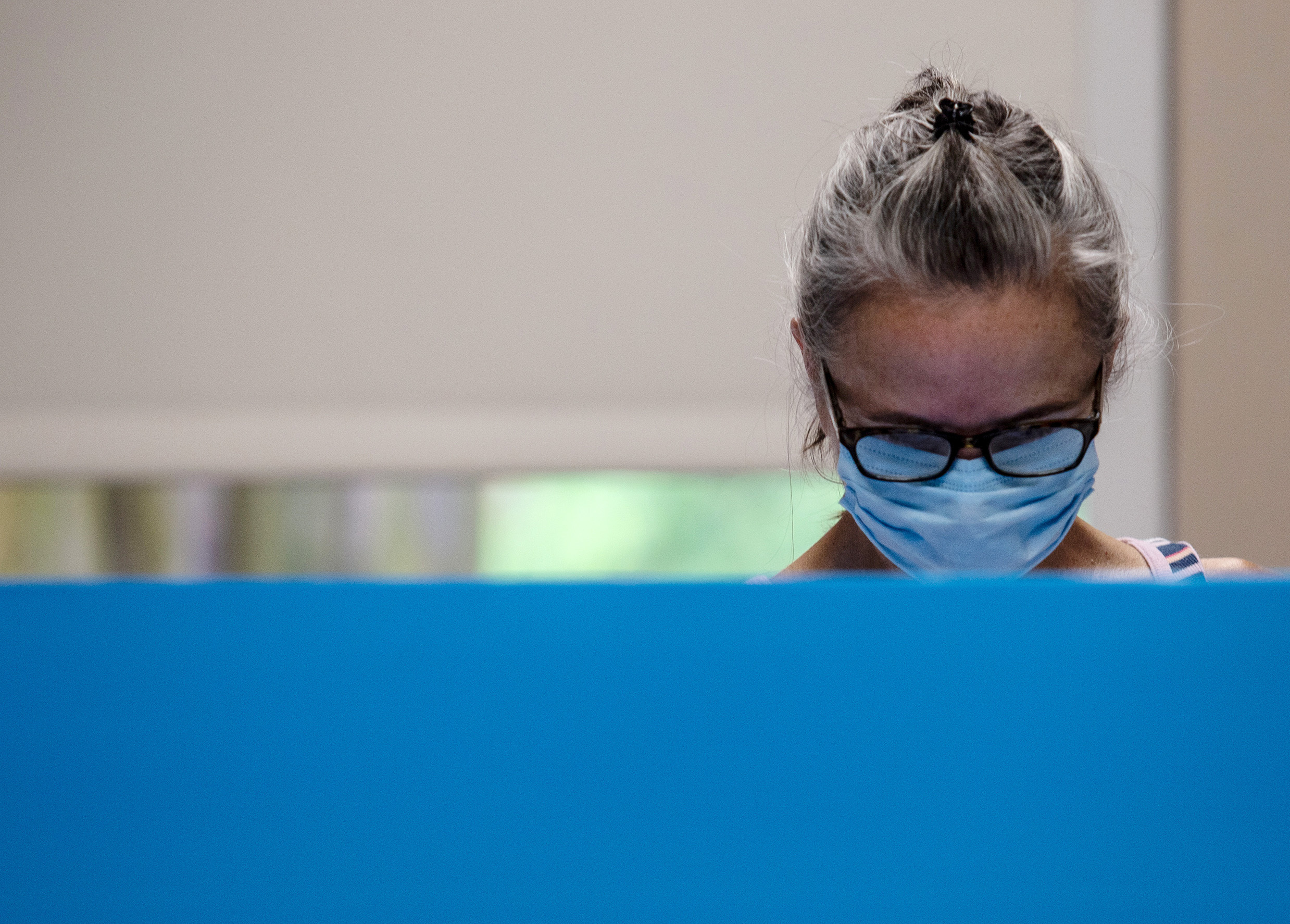

Ron Harris / Associated Press file

One of the issues Georgia voters will decide on in November is about amending the state constitution to allow lawmakers to specify how money from fees gets spent.

As it stands now, lawmakers can create fees — and the funds that the money from those fees flows into — but they can’t prevent that money from going to the state’s general fund instead.

The first question listed under the proposed constitutional amendments section on Georgia ballots would change that.

A “yes” vote is a vote to allow Georgia lawmakers to dedicate money from fees to the funds that the fees are supposed to be for in the first place.

“Let me say it this way,” said supporter Hattie Portis-Jones, a Fairburn City Councilwoman, “we have coined this amendment, the ‘trust fund honesty amendment,’ and I think that name speaks for itself.”

‘Not Enough Money To Go Around’

To illustrate the problem the amendment seeks to solve, Fletcher Sams from the environmental group Altamaha Riverkeeper visited a spot in Conyers that looks like many vacant lots: chain-link fence, lots of weeds.

But there used to be a car battery recycler there, Sams said, and the place is still polluted with antimony, cadmium and lead.

It’s the kind of thing where usually the owner would be held responsible for cleaning up the pollution, but this site is abandoned. So it falls on the state to do the cleanup. There are about 60 abandoned sites like this around Georgia.

“There’s no one to hold accountable,” Sams said. “And there’s not enough money to go around all these abandoned sites.”

The spot Sams was standing outside of has been on Georgia’s Hazardous Site Inventory since 1994. That length of time isn’t unusual.

There is a fund that’s meant to help the state pay for these kinds of cleanups, but the money Georgia collects to go to that fund often gets used in other ways.

According to an analysis by Georgia’s County Association, ACCG, between 2009 and 2019, 60% of the fees have gone to the state’s general fund instead of to the Hazardous Waste Trust Fund, adding up to close to a $100 million diverted.

Another fee that’s had money diverted is the scrap tire fee, collected whenever someone buys a new tire. The fund is intended to help cleanup illegal tire dumps and abandoned landfills, but during the same time period, nearly 70% of funds were redirected, according to ACCG.

The constitutional amendment on the ballot in November would give state lawmakers the power to say, “when we set a fee, and say that money is going to something, it has to actually go there.” It wouldn’t be automatic; they’d have to vote to dedicate funds. And if there’s a fiscal emergency, the state could still use the revenue in other ways.

The vote to put this amendment on the ballot was bipartisan in the General Assembly and passed overwhelmingly.

Sams said he hopes if money does get directed toward cleaning up abandoned sites, that will free up other money for the state Environmental Protection Division to spend on finding more sites that need cleaning up, and working on the hundreds of polluted sites where there are owners, but there are still problems.