Georgia's Dugdown Corridor: A 'national model' for conservation

Last year, a group of scientists and volunteers splashed up a creek in Paulding County to look for endangered fish.

It didn’t take long to find them.

With two people holding a net upright underwater and others shuffling downstream to shoo fish into it, the team hauled up a handful of Etowah darters the first time they tried.

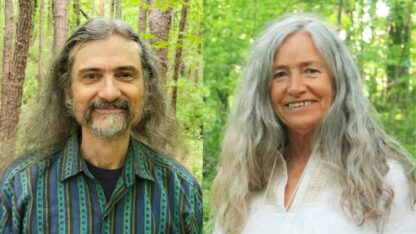

“That’s pretty cool,” said Bill Ensign, a retired Kennesaw State University professor, as he picked the rare fish out of the net, tallying them as he went along.

The colorful little Etowah darters live in a handful of counties in northwest Georgia, and nowhere else in the world. They’re unique to the Etowah River and some of its tributaries, including Raccoon Creek, where the day’s sampling expedition was happening.

Those darters are just one of the unique freshwater creatures living in the region.

Thanks to some quirks of geology and the last ice age, this corner of Georgia, along with northeast Alabama and neighboring parts of Tennessee, is a global hotspot for freshwater fish, and creatures like mussels and crayfish, too.

It’s an “incredible” place of biodiversity, according to Katie Owens, Upper Coosa River program director at The Nature Conservancy. Close to 80 species of fish live in the Etowah River basin alone.

“I like to think it’s a miniature Amazon right here in our backyard,” said Owens, who’s based in west Georgia.

Efforts to protect that rich biodiversity have become a jumping-off point for an ambitious conservation project taking shape in west Georgia — protecting and restoring not only Raccoon Creek, but miles and miles of land around it, too, expanding public access, bringing fire back to forests that depend on it and creating a refuge for wildlife as the changing climate alters ecosystems.

The Nature Conservancy is working with the State of Georgia, Paulding and other Georgia counties, The Conservation Fund, Kennesaw State University, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and others on the project — it’s called the Dugdown Corridor. Named after a mountain in the area, it’s a vision for a giant connected network of forests and streams, stretching from the edge of metro Atlanta to the Talladega National Forest in Alabama.

A coordinated effort

As remote as it might seem — a relatively rural area of tree farms and wildlife management areas for hunting — one end of the corridor is barely an hour’s drive from downtown Atlanta.

“A lot of people don’t realize this is one of the most unique places in Georgia right here,” said Tim Pugh, the environmental compliance division manager with Paulding County.

Pugh, who was helping with the fish research at Raccoon Creek, grew up in the area.

He said the location, where three of Georgia’s geographic regions meet and mix — the Ridge and Valley, the Blue Ridge Mountains and the Piedmont — accounts for the unusual combination of wild plants and animals.

“It’s why we have all these odd plants, odd fish, odd rocks, odd everything,” he said.

Pugh said there’s a land ethic in the area at the edge of sprawling Atlanta, a sense that people don’t want the whole county to get developed.

“There’s a lot of families that have been here since the land lotteries in the 1800s,” he said. “So there’s a lot of people [with] deep roots here, that want it to stay.”

Pieces of property have been protected over time.

The state bought land in the area in the late-1980s to create Sheffield Wildlife Management Area, and later added a second neighboring wildlife management area called Paulding Forest.

In 2007 Paulding County helped buy some of that land after residents voted to tax themselves to pay for it. At the time — before the Great Recession — the housing market was going nuts, and Paulding was growing fast.

Brent Womack, a wildlife biologist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and a supervisor in the region, credits voters and the county for deciding to spend the money when they did.

“The writing was on the wall, if we don’t do something now to try to retain at least a piece of this it’s going to be gone,” he said. “It’s easy for people to say, ‘Yeah, we like greenspace.’ But you have to do things sometimes to really put your money where your mouth is and make it happen. And that’s what the county did.”

Womack can trace his family’s history in the area back to the middle of the 19th century. He said he never thought when he was growing up in Paulding County, imagining a future as a wildlife biologist, that he would get to work so close to home. “It’s pretty neat,” he said.

Between Sheffield and Paulding Forest Wildlife Management Areas, there are now about 50 square miles of public land for people to use, most commonly for hunting, but exploring through other means is an option for the adventurous. (Unlike at state parks, there aren’t bathrooms or marked trails in these largely wild areas). The Silver Comet trail travels through a portion of it.

Meanwhile, the conservation has continued — the state has added bits and pieces of property to the wildlife management areas as it’s been able to.

The broader Dugdown Corridor project is even bigger than that, though: A patchwork of public lands and privately-owned forests in an area covering around 200 square miles.

The western edge of the corridor shares a border with the Talladega National Forest in Alabama.

“We really are trying to think big picture,” Owens said.

That matters for delicate wild places, like Raccoon Creek.

That day in the creek, the team counted what they caught, tossed the fish back, then splashed their way further upstream to do the whole thing many times over again.

Ensign said what happens on land affects nearby waterways. Pollution and erosion can ruin places like this, where the endangered fish live.

“Once human development begins, those sorts of habitats are some of the first that disappear,” he said.

Forest land

It’s not just those fish and their sensitive streams that are special in this area. There are also forests here that grow almost nowhere else in the world.

On a different day, in a different part of the corridor, Owens looked across a hillside of blackened young longleaf pines. A fire had come through recently. But Owens said most of the trees would be fine; they’re adapted to fire, and this blaze was an intentional, prescribed fire to maintain the health of the forest that’s growing here.

“It looks a little bit desolate right now, with a lot of brown trees, a lot of brown needles,” Owens said. “Grasses and ferns and things are the first things to come back in greenery. It’s a really great transformation from burn day to just a few weeks later.”

Longleaf pines, an iconic Southern tree, used to cover 90 million acres across the Southeast. Now, they occupy a tiny fraction of that area.

The tall straight-trunked trees with round puffs of long needles are typically associated with the sandy coastal plain, but they grow here on rolling hills far from the ocean.

The groups working together on the Dugdown Corridor are focused on these montane longleaf forests, too, which only grow in the northwest corner of Georgia and northeast corner of Alabama.

The recently burned site had been a loblolly pine plantation until just a few years ago, Owens said. After the state Department of Natural Resources, which manages the property, harvested those trees, The Nature Conservancy came in to plant longleaf in its place, and to help maintain the new forest with the fire it depends on.

Owens also works with private landowners in the area on using controlled burns and managing their property with conservation in mind.

And for property owners that want to sell, including big investors, The Conservation Fund is buying timber land in the area to add to the corridor.

At a site the organization had recently bought, forest operations manager Jenna Schreiber looked on as a team cut loblolly pines, preparing them to go to a local mill. The trees had been planted by a previous owner for harvesting.

Though it might seem counterintuitive for an environmental group to cut down trees, Schreiber said it’s part of what The Conservation Fund does.

“Conserve large tracts of land, working forest land, supporting rural communities, supporting rural jobs,” she said.

And the money from cutting the trees helps fund the conservation work, she said.

The Conservation Fund and others working in the area say keeping working timberland is helpful for the corridor, too — as long as it doesn’t end up getting developed into housing or shopping centers.

“There’s increasing pressure on these larger tracts of undeveloped land to be cut into smaller pieces,” said Andrew Schock, state director at The Conservation Fund.

Protecting big chunks of land is important, Owens said, not just for recreation and wildlife now, but also looking to the future as climate change affects Georgia’s wild places.

The Dugdown Corridor will be able to serve as a refuge as animals move because big areas like this provide a place for them to go.

“We look at areas across Georgia and say, ‘Where are species going to move in terms of climate impacts?’ And this whole corridor, the Dugdown Corridor, lights up in terms of climate resiliency,” she said.

The state Department of Natural Resources identifies Sheffield and Paulding Forest Wildlife Management Areas as a high priority in its 2015 wildlife action plan, citing the “globally significant” forests and the Raccoon Creek watershed in all of its biodiversity.

Pausing in the creek that summer day doing fish sampling, Ensign said Raccoon Creek would likely never be restored to some kind of pristine state, “but we can protect, and we can also live in a way that minimizes what we know causes damage.”

He said the science exists on how to do less harm, but it’s a societal decision on whether or not to follow it. On the collaborative approach of the groups working to piece together the Dugdown Corridor, he said it should be held up as an example of what’s possible.

“It’s a national model,” Ensign said.