GSU Professor Explores How Children’s Books Teach Human Rights

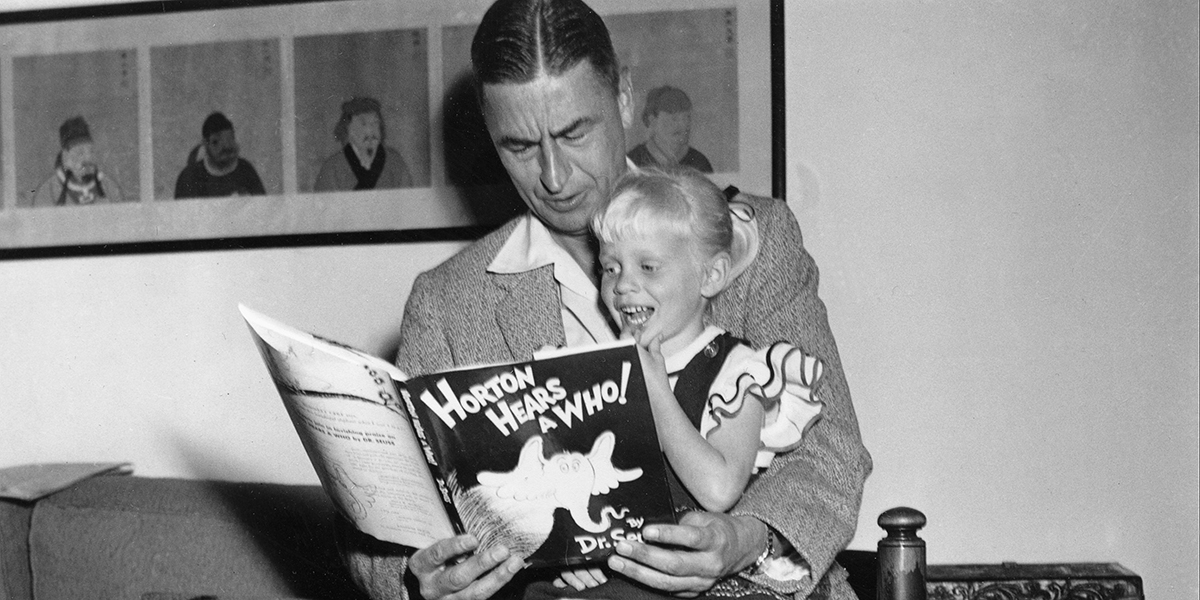

Author and illustrator Theodor Seuss Geisel, known as Dr. Seuss, reads from his book “Horton Hears a Who!” to four-year-old Lucinda Bell at his home in La Jolla, Ca., June 20, 1956. (AP Photo)

What can we learn about discrimination from Dr. Seuss? Or standards of living from the “Three Little Pigs?”

Plenty of children’s books teach morals and lessons, but those morals and lessons can teach children about something more: their human rights.

That’s the argument from Georgia State law professor Jonathan Todres, who co-authored the book “Human Rights in Children’s Literature: Imagination and the Narrative of Law” with Sarah Higinbotham, who teaches law and literature at Georgia Tech.

“This project is a natural outgrowth of what I’ve done for many years, focusing on children’s rights and thinking about how we prevent harm occurring in the first place,” said Todres.

At the same time, he said, it wasn’t until stumbled across “Horton Hears a Who!” in the library that he had the idea for the topic.

“And I came across that iconic line, ‘A person’s a person no matter how small,’” he said. “And I thought, that’s a clearer explanation of core principles of human rights than any legal scholar or philosopher has come up with.”

Todres and Higinbotham studied about 500 children’s books and identified how the messages in the books can have an impact on the children reading those books. “Horton Hears a Who!,” for example, impresses readers that every voice matters. “Peter Rabbit,” on the other hand, makes the impression that children should be seen and not heard, as only adults speak in the book.

Their research revolves around the Convention of the Rights of the Children, the most widely accepted human rights treaty in history. It says that not only must children have certain human rights, but they must know that they have them.

“The fundamental point for me is, how we expect young adults, or adults generally, to exercise and realize their rights if we don’t expose them to these ideas early,” Todres said. “You don’t just magically turn 18 and suddenly know your rights … You have to practice that as a child.”

Todres said his book is part of a larger project on the intersection of human rights and literature.