The Gulch Could Have A New Future. Here’s A Look At Its Past

The history of the Gulch is more than just the paving over of some railroad tracks to make a parking lot.

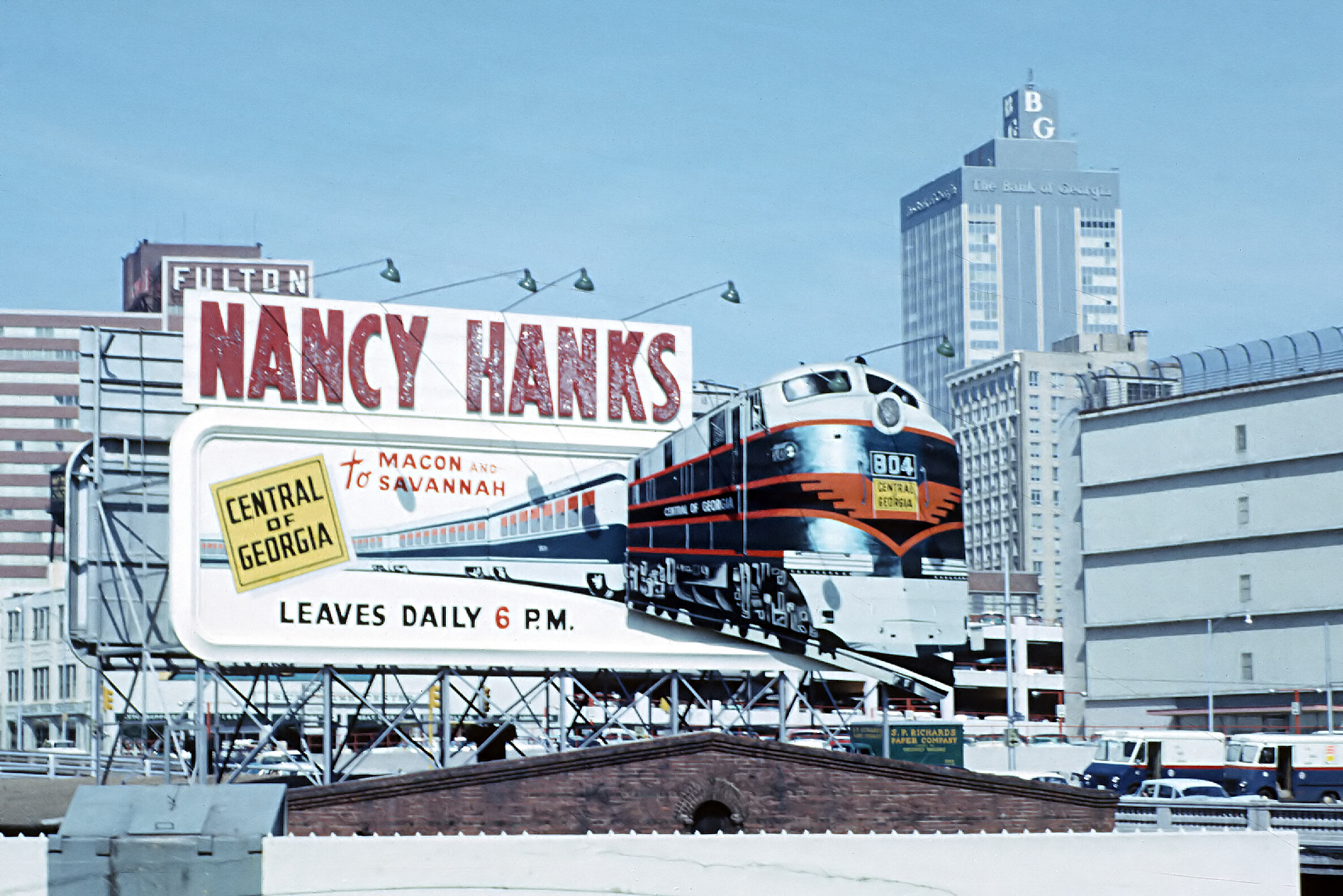

John Bazemore / Associated Press

Thanks to the recently-approved $5 billion Gulch deal proposed by development firm, CIM Group, Georgians can look forward to a future that could reshape the look of Atlanta as they’ve known it.

What’s currently an empty lot-turned-prime tailgating spot is slated to become a new “mini-city” with the potential to alter the city’s skyline.

But the history of the Gulch is more than just the paving over of some railroad tracks to make a parking lot. The history of the Gulch helps reveal the history of Atlanta itself, and it’s one worth looking back on as the city faces a new future.

‘Atlanta’s Original Commercial Heart’

Atlanta as it’s known today began amid soot, steam and smoke as a railway corridor for lines that linked cotton and farming states in central part of the country to the East Coast.

“The area south of the Gulch was Atlanta’s original commercial heart,” says former Atlanta architect and planner, Richard Rothman. “The second part is north and west of the tracks, and is where most of the city’s original resident growth had occurred.”

In the mid-1800s, engineer and colonel Lemuel Pratt Grant helped to construct the Georgia Railroad, one of those first three railways that would form the corridor.

Two other railroads came after, says Boyd Coons, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center.

“One that went North and one that went South. Georgia Railroad, the Western and Atlantic Railroad, and the railroad that went to down to Macon came together in what is now the Gulch,” he says. “That was demarked in 1850 with the Zero Mile Post.”

The Zero Mile Post was the end-point of the Western and Atlantic Railroad, and its location is considered by many, including Coons, to be the true beginning of the city, post-Civil War.

This railway terminal turned Atlanta into a transportation hub, one that saw roughly 350 trains pass in and out of the city each day.

Constructing The Viaducts

While the railroad corridor of those three main lines was critical to Atlanta’s commercial and economic growth, it was also loud, smoky and dangerous. Trains blocked street crossings, backed up traffic and made walking from one side of town to the other treacherous for pedestrians.

“If you’re old enough to have ridden on a steam train, which I am, the cinders and everything that came out of there, it was just amazing,” says Coons, “and I think in an era before any other sounds, no television, no radio, no intrusions, [people] may have found this exciting and invigorating. But by the [turn of the century], it was a major impediment to commerce, and to just traveling the city.”

I think a great city keeps the best of its past.

Boyd Coons, executive director of the Atlanta Preservation Center

Coons’ own third great grandfather was killed just a few feet from the Zero Mile Post in 1849 by the sudden reversing of a train.

In 1909, the Ford Motor Company declared Atlanta the representative city of its southeast branch. Combined with the traffic problems and issues with pedestrian safety, this influx of automobiles made Atlanta’s passenger trains a much less popular means of travel. As a result, the city constructed a series of viaducts, or bridges, above the track that raised the streets of the city above its original ground level.

Says Rothman, “a gulch was created when streets crossing the rail tracks were elevated one level by a network of viaducts to allow pedestrians, vehicles and electric streetcars to pass over the tracks independent of train traffic below.”

By 1938, that connected viaduct network was complete.

Vacancy And possibility

By the latter part of the twentieth century, passenger train travel was all but obsolete in the city. Atlanta had removed most of its train tracks, including the ones in the Gulch, which left behind roughly 40 acres of undeveloped land—and plenty of development opportunity.

In 1958, architectural firm Toombs, Amino & Wells proposed a “new town in town” that would have reopened the Gulch’s lower-level streets to the expressway being constructed at the time. The Skidmore, Owings & Merril Park Place plan of 1966 proposed a multi-use complex of apartments, hotels, offices and retail at Underground Atlanta. Air rights developments of the late 1960s by Cousins Properties, Inc., resulted in the construction of The Omni and Omni International at the northern end of the Gulch.

The mid-1970s saw air rights plans from Central Atlanta Progress to revitalize the vacant buildings around the Gulch for retail opportunities and residential development.

Between 1950 and 1980, no less than 10 proposals had been presented to the city for the area’s redevelopment.

Rothman moved to the city from Chicago in 1970.

At that time, he says, “Atlanta was suburbanizing while practically abandoning its heritage and investment in downtown and the inner city. I knew the importance of helping maintain the viability of our downtowns and urban neighborhoods, and I chose a job in Atlanta because the firm I’d join was in line to become the planner for a large air rights project that’d bridge Atlanta’s downtown railroad Gulch.”

Rothman spent the next 28 years working to breathe “new life into old downtown,” an effort that many others undertook as well, and that the city saw culminate in the recent CIM Group development deal.

The Future Of The Gulch

The city approved CIM Group’s proposal for the Gulch on Nov. 6., and Atlanta Public Schools recently reached a deal that ends its dispute with the city over funding for the project.

CIM’s plan includes potential new retail and office space, green space, housing options, and an entirely new street grid.

Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms declared in a press release issued by her office that “the Gulch redevelopment deal, the largest in state history, charts a new course for how city development is optimized for public good,” and assured residents that the deal is inscribed with things like affordable housing and minority and female-owned business participation.

But some, like Coons, say that without at least some attention paid to the area’s historical significance, the development plan would also serve to further divorce Atlanta from its unique railroad heritage, much of which has already been lost.

“For me, it’s [about] a sense of place,” Coons says. “When I look around Atlanta now, I see the kind of expedient, shoddy, banal development that goes on that just seems to be filling space. I think a great city keeps the best of its past.”

The city’s Union Station was demolished in 1970, its Terminal Station razed in 1971. Railway company Norfolk Southern demolished Terminal Station’s Interlocking Tower in June to prepare for the sale of the Gulch. The Zero Mile Marker was also removed this year accommodate an entrance to a temporary parking garage, though it has since been moved to the Atlanta History Center.

So far, there hasn’t been much comment on historical preservation and the Gulch’s newly greenlit redevelopment by either the city or CIM Group. Attempts to request comment from the Atlanta City Council for this story were unsuccessful.

But Coons and other historic preservationists hope that at least some attention is paid to the fact that this new construction will be done on the site of the very beginnings of Atlanta, one of the few spots left that preserves the place where the city’s unique story began.

“Atlanta really is a great city,” he says. “It really does have an indigenous culture, and it really does deserve to have that expressed here.”

Related: More WABE coverage on the Gulch >>