Health officials warn mpox threat is not over

The health emergency caused by mpox has concluded, but U.S. health authorities are striving to prevent a recurrence of the spike in outbreaks experienced last year.

In the summer of 2022, mpox infections surged following Pride events, resulting in over 30,000 reported cases in the U.S., primarily transmitted through sexual contact among gay and bisexual men. Approximately 40 fatalities occurred.

As Pride events are taking place nationwide this month, health officials and event organizers have expressed optimism that this year will see fewer outbreaks and less severe infections. Factors such as increased vaccine supply, higher immunity rates and improved access to mpox treatment contribute to this optimism.

Dr. Melanie Thompson is a local HIV researcher and treatment provider, and she has been closely involved in efforts to reduce the spread of mpox.

She said while Georgia ranks fifth in the nation for its number of mpox cases, it is a concern that people may view mpox as a problem of the past.

“It’s really timely to be talking about mpox, because it’s not gone,” said Dr. Thompson. “And we want to be sure to be ready for it if another outbreak tries to occur.”

Recently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health alert to U.S. physicians to remain vigilant for new cases. Additionally, the agency published a modeling study that assessed the likelihood of mpox resurgence in 50 counties targeted by the government’s campaign to control sexually transmitted diseases.

Thompson said the disease has not affected all populations equally.

“The people who have got the most serious cases of mpox, including being hospitalized and unfortunately dying, are disproportionately people with HIV,” said Dr. Thompson.

She also said there are racial disparities in which groups are getting vaccinated, which she said suggests health agencies need to focus their efforts more equitably.

According to Dr. Thompson, many people got the first shot of the vaccine when cases were at their peak last year, but might have never got the second shot. She points out that it’s still not too late, and the vaccine is much more effective with both doses.

She said it’s also important to build awareness among health providers and in the community so that anyone with symptoms that could be mpox knows to get tested.

“We have a long way to go in terms of community awareness because many people don’t know they have mpox just like they don’t know they might have another sexually transmitted infection,” said Dr. Thompson.

Health officials are trying to instill some sense of urgency regarding a health threat that was considered a burgeoning crisis last summer but diminished by year-end.

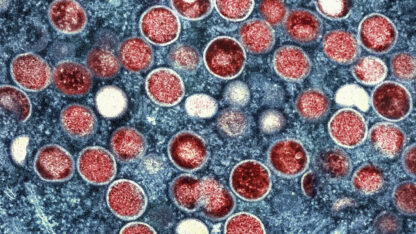

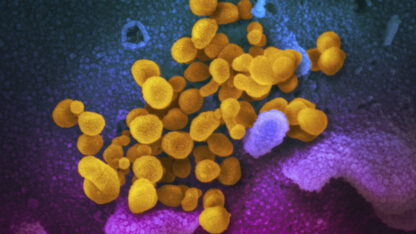

Formerly referred to as monkeypox, mpox is caused by a virus belonging to the same family as the one responsible for smallpox. It is endemic in certain regions of Africa, where individuals have contracted it through rodent or small animal bites. However, it was not known to spread easily among humans.

Around a year ago, cases emerged in Europe and the U.S., primarily affecting men who have sex with men, and the situation escalated in numerous countries in June and July. While infections were rarely fatal, many individuals experienced painful skin lesions for weeks.

Countries scrambled to find vaccines and other countermeasures. In late July, the World Health Organization declared a health emergency, followed by the U.S. in early August.

However, cases began to decline, dropping from an average of nearly 500 per day in August to fewer than 10 by late December. Experts attributed the decline to various factors, including government measures to address vaccine shortages and efforts within the gay and bisexual community to raise awareness and reduce sexual encounters.

The U.S. health emergency ended in late January, and the WHO lifted its declaration earlier this month.

During the peak of the crisis last year, there were long queues for vaccinations, but demand waned as cases declined. The government estimates that 1.7 million high-risk individuals, primarily men who have sex with men, are susceptible to mpox infection. However, only around 400,000 have received the recommended two doses of the vaccine.

This year, cases have emerged in certain European countries and South Korea. Additionally, officials in the U.K. announced a recent rise in mpox cases in London, indicating that the virus is still present.

Nearly 30 individuals, including vaccinated individuals, were infected in a recent outbreak in Chicago.

Similar to COVID-19 and the flu shot, vaccinated individuals can still contract mpox, but their symptoms are likely to be milder, officials explain.