It was the early 1990s in Atlanta when Malcolm Reid first felt the lymph nodes on his neck seemed swollen.

“And I read an article in Ebony Magazine. That’s when they were still talking about the ‘gay cancer,’” Reid said, wondering, “Is this gay cancer? What is this?”

Gay cancer — an early nickname for the mysterious illness that later became known as AIDS, or Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.

At the time, cases were rapidly escalating. And men who have sex with men were at especially high risk for human immunodeficiency virus or HIV, the virus that without treatment can become AIDS.

Reid’s mom was a nurse.

“And I remember going to a phone booth on Ponce and calling my mother. I was crying and my mother asked, what’s wrong? And I was like, well, my lymph nodes are swollen and I think this is what’s happening,” he said.

Reid knew there was no cure. And the treatments that existed then were often expensive and could cause debilitating side effects.

“Back in the 1990s, you were scared to death to get tested because if you got tested, it was positive, you were going to die,” he said. “Friends of ours were dying, you know? In the late 1980s and early 1990s, I just couldn’t go to funerals anymore. I just stopped going,”

Eventually, he got tested and the results confirmed his suspicions. He was HIV-positive.

Looking back, Reid said he was “blessed” to have had good health insurance at the time of his diagnosis and afterward.

And today, with treatment, his HIV is undetectable.

“People say, how can you say you’re blessed, you’re living with HIV? Do you know how many people have died? I’m still here. I’m 65 years old,” he said. “I’ve been living with HIV since I was 39.”

“When you put that in the context of how fast a COVID-19 vaccine was made — in less than a year — it’s really telling that this is an incredibly difficult task for the scientific community.”

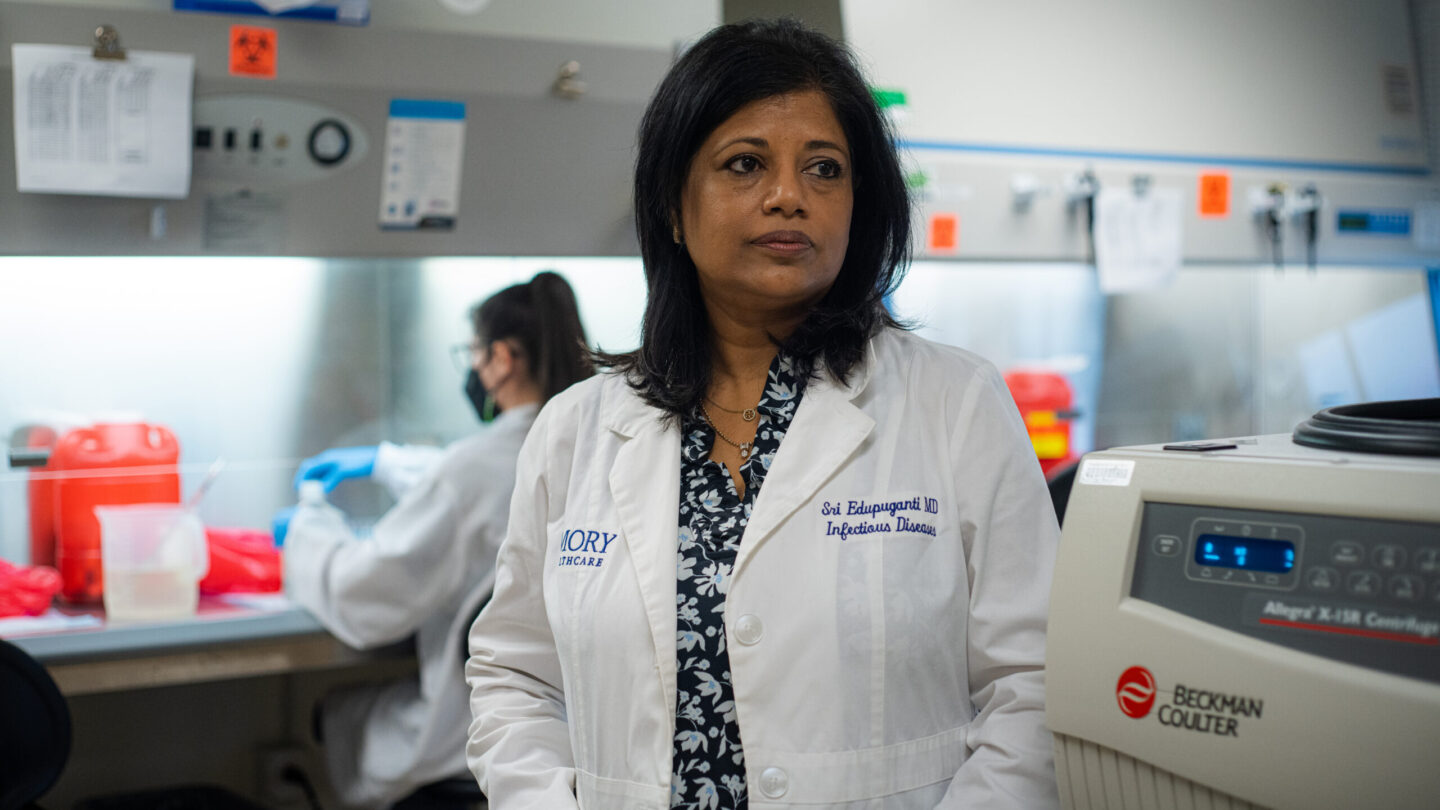

Dr. Sri Edupuganti on the 40-year search for an HIV vaccine.

Still, the program director of Thrive SS, a nonprofit HIV advocacy organization focused on communities of color, knows that so many people living with HIV in metro Atlanta are not doing as well as he is.

Georgia has the highest rate of new HIV diagnoses of any state in the U.S., and Atlanta has the second-highest rate of new diagnoses of any metropolitan area, according to the Atlanta-based Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

About 80% of new HIV diagnoses in Georgia are among men, and particularly men who have sex with men. Black and Hispanic Georgians are also disproportionately affected.

For the last year, researchers at Emory University have collaborated on what could become a first-ever HIV vaccine, using the same mRNA technology that dramatically accelerated the availability of COVID-19 shots during the pandemic.

This ongoing research is happening after decades of failed attempts to produce a vaccine to effectively fight HIV.

A vaccine would prevent HIV-negative people from getting infected. A different Emory research team is leading a study for an HIV cure, which would wipe out or put in permanent remission an HIV infection.

Cautious optimism at the Hope Clinic

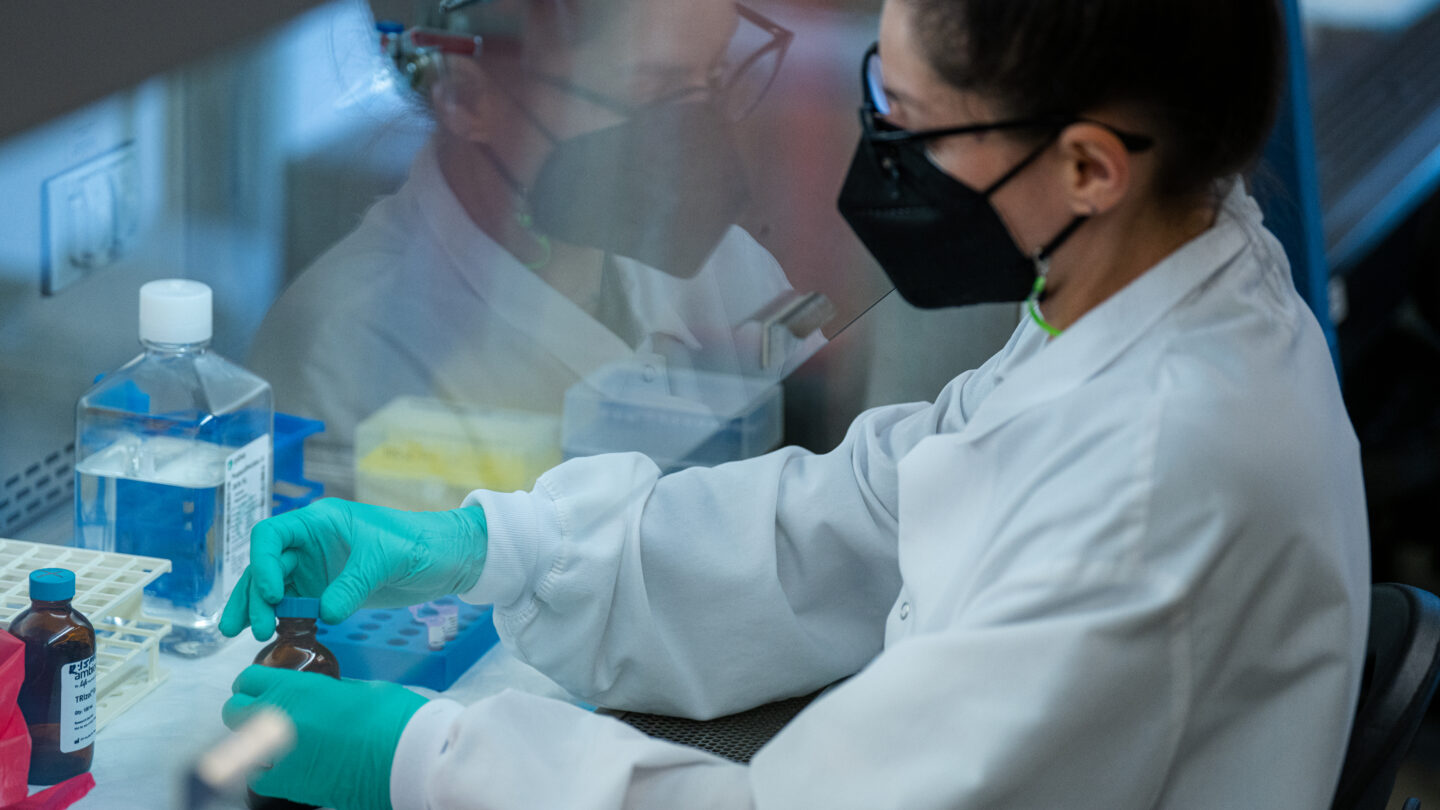

At an Emory University building in Decatur, one of four sites around the U.S. working on a Phase I clinical trial to test the HIV vaccine, researchers in white lab coats, protective gloves and goggles hustle around a windowless lab processing blood samples in glass vials.

Down a hallway, Clinical Research Nurse Renata Dennis examines a patient participating in the vaccine trial.

“Alright, and I’m going to have you come sit up here for me,” she said, motioning to the exam table.

This patient is one of just under 60 HIV-negative people around the country volunteering for the trial.

Researchers have given each patient one or two doses of the vaccine over the last six months to test their immune responses.

During regular patient visits, Dennis said she checks vital signs, draws blood and asks a lot of questions designed to assess whether participants are experiencing any adverse health impacts from the trial.

“Do they have a fever? Do they have muscle aches? Have they had any side effects that can be attributed to the vaccine?” she said.

It’s been almost 40 years since scientists first discovered HIV is the cause of AIDS. Dr. Sri Edupuganti has been researching an HIV vaccine for almost 20 of those years.

“When you put that in the context of how fast a COVID-19 vaccine was made — in less than a year — it’s really telling that this is an incredibly difficult task for the scientific community,” she said.

Edupuganti is an infectious disease physician and the lead researcher for Emory’s HIV vaccine trial at the Hope Clinic of Emory Vaccine Center.

HIV is extremely difficult to tackle with a vaccine, she said.

“Because once it infects the cell, it integrates into our DNA,” she said. “So we can’t get rid of it because it’s in our DNA.”

Amid the current trial, Edupuganti is cautiously optimistic that the mRNA technology that helped create the COVID-19 vaccine could potentially help with HIV, too.

“The mRNA vaccines are also quick in terms of the production,” she said. “They’re relatively cheap. And that’s how they came into being so quickly for COVID.”

But it still has a long way to go. If the vaccine works in this early phase, next steps would include testing it in thousands more people.

“In the real world where people are acquiring HIV, you have to test it in that situation. I’ve learned not to get too excited until we get there and see what the data looks like because you don’t want to get too disappointed after that,” she said, “because you know, you’ve really been burned so many times that you really have to temper your excitement, I guess.”

A thrilling prospect

In an event space at the back of Thrive SS, a long table is decorated with balloons from a recent gathering the group threw for older Black men living with HIV.

Malcolm Reid said the prospect of a potential mRNA vaccine for HIV is thrilling.

But as a person living with longtime HIV himself, he said it’s critical that any future vaccine reaches the communities that need it most.

“We need to have a seat at the table to make sure that things are done equitably in the areas that are hardest hit,” he said. “If there’s going to be a vaccine, who is going to get it? How’s it going to be covered? You know, people with insurance, do they get it? Without insurance, do they get it? You know, all of those questions that we would want to know.”

And, Reid said he hopes for a time when people won’t have to go through what he and so many others have experienced living with HIV.

Click here for more information about Emory’s HIV vaccine trial, including how to become a trial volunteer.

This story is part of the ongoing series Beyond Pride, in which WABE reporters take a deeper look at the issues affecting LGBTQ people in Georgia. Plus, hear LGBTQ Atlantans in their own words, check out a Pride events calendar running through the fall, LGBTQ coverage from other NPR stations across the South and more.