In Anashay Wright’s suburban Atlanta home, President Trump’s name is seldom spoken. But this week, he’s been hard to ignore.

“There’s something to people who don’t get their way, and they have temper tantrums like him,” Wright said. “The fragility, because something don’t go your way? How dare you?”

Trump has – without evidence – accused Democrats of perpetrating a “fraud” on the American people, and launched a flurry of lawsuits in Georgia and other states aimed at questioning the election results.

But to his supporters, such as Catherine McDonald in Atlanta’s Buckhead neighborhood, what’s unfolding now seems to confirm the warnings she’s heard from the president and conservative media.

“I have been hearing about this for months, if not the last year, that there were going to be a lot of challenges. That with how divided the country is, that the Democrat side was fully prepared to cast as much doubt as possible on the outcome,” McDonald said.

A close vote, a slow process

To be clear, election experts have been predicting for months that counting early and absentee ballots would take some time due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Tensions around the 2020 election results are especially high in Georgia, a state that has not been won by a Democratic presidential candidate since 1992. Election results are coming down to the narrowest of margins this year, and officials have promised a recount.

“We are literally looking at a margin of less than a large high school,” Gabe Sterling, an official with the Georgia secretary of state’s office, said during a Friday morning press conference in Atlanta.

Georgia’s growing and increasingly diverse suburbs, combined with organized, well-funded, get-out-the-vote efforts by Democratic activists, have propelled Georgia into the swing state category.

“Blue-ing” of the suburbs

Amy Steigerwalt, a political science professor at Georgia State University, said there are many reasons why Georgia is now in play – among them an increasingly diverse electorate, which includes a growing Black middle class and increasing numbers of Asian and Latino voters.

“The ‘blue-ing’ of the suburbs is probably the biggest thing that’s happening,” she said. “These areas that have long been Republican strongholds are not anymore.”

Steigerwalt also gives substantial credit to activist and former gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, whose Fair Fight organization worked to register and mobilize voters statewide after her narrow – and controversial – loss to Republican Brian Kemp in 2018. The group raised about $40 million from more than 200,000 donors nationwide to turn out Democratic voters in Georgia and other key states, according to a spokesman.

The Atlanta area will remain a focus of voter turnout efforts as both parties look toward two potential runoffs in January that could decide control of the U.S. Senate.

One state, two realities

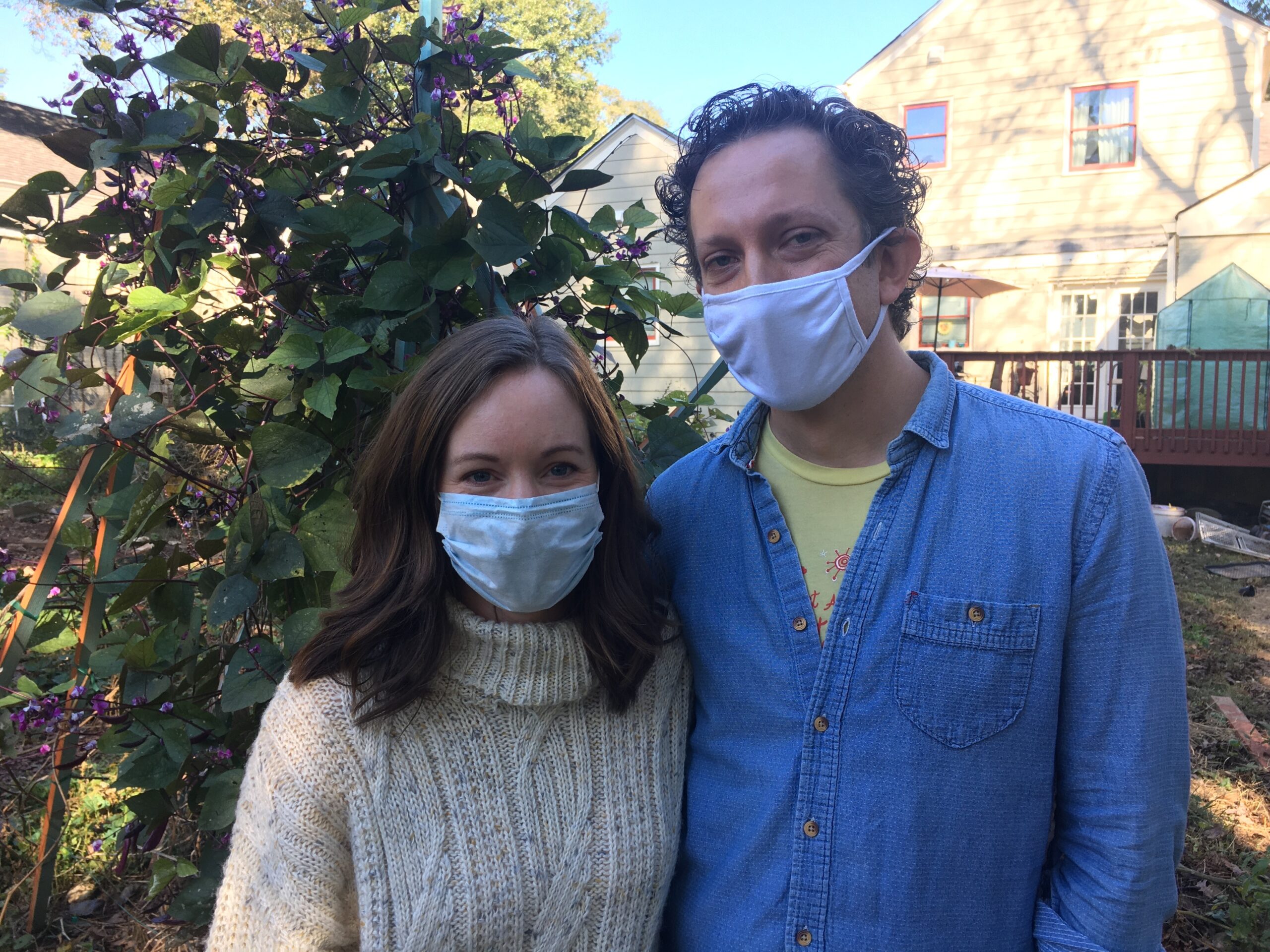

While the results of the presidential race look promising for Democrats in a state the party has not won since 1992, it’s all too close for comfort for some Biden supporters such as Eric Mendenhall of east Atlanta.

“I was hopeful that it would be decisive and clear and that that there would be a denouncement of the last four years that we could at least see a general consensus across the country that this isn’t who we are,” he said.

His wife, Bethany Lind Mendenhall, said she worries that divisions in the state, and the country, have been once again laid bare by this election.

“We have family members who listen to completely different voices and news sources than we do,” she said. “We see things very differently. But I want to be able to have conversations. But it’s like we’re operating in different realities.”

In midtown Atlanta, retired lawyer and Vietnam veteran Al Lindseth said he reluctantly voted for Trump. He dislikes Trump’s demeanor and said he almost didn’t vote for the president after his first debate performance, which he found rude.

But Lindseth said he’s concerned by where he believes the left wing of the Democratic Party wants to take the country.

“People are so easily offended these days. People are concerned about division now; they should have been here in the ’60s when we had rioting in the streets. We were worried about going to a war and getting shot,” he said. “I just think we worry about a lot of things in this country, and they’re not our major concerns.”

Lindseth said he wouldn’t mind a Biden presidency terribly as long as Republicans hold the Senate.

A ”false sense of unity”

Back at her home in suburban Atlanta, Wright said a Biden presidency could buy some time for Americans to pause and reflect on the future after a tense four years.

Whatever the outcome of the election, Wright said she hopes the lessons of the Trump years won’t be forgotten.

“I think what Biden offers is – I hate to say it – like this false sense of unity, right? What I’m scared that might happen is that people actually might get comfortable again,” Wright said. “That’s my biggest fear.”

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))