How Plants And A Civil War-Era Book Help Emory Scientists Search For New Drugs

In a study published Wednesday, an Emory University professor looks to plants – and Civil War history — to search for ways to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Kaitlin Kolarik / Special to WABE

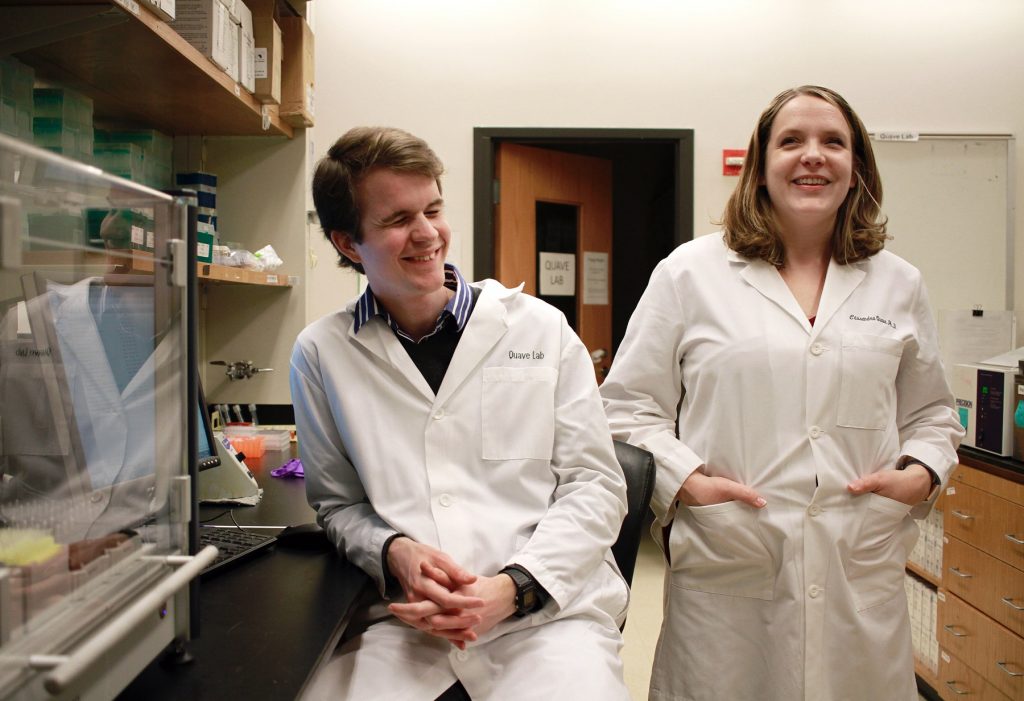

Cassandra Quave studies plants and how people use them as a professor at Emory University. She travels around the world, collecting samples and learning about traditional uses of plants, looking for clues that might lead to new medicines.

She’s especially interested in antibiotic resistance. Here in the U.S., at least 2 million people get drug-resistant infections every year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and more than 20,000 people die.

In a study published Wednesday, Quave looks not only to plants but also to Civil War history to search for ways to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Plants Are Good At Chemistry

It makes sense to look to the plant world when searching for new drugs, Quave says, because plants are really good at coming up with complicated chemical compounds.

“Plants are in an interesting evolutionary situation,” she says. “They cannot get up and move away from a threat; they cannot go toward a resource. Instead, they’re completely dependent on their ability to use their own chemistry to communicate with other organisms in the environment.”

For example, they use chemistry to attract pollinators with flower colors and smells. Some plants taste good; some make us itchy; some are toxic. That’s all thanks to chemistry.

And many plants have been used before in developing medicines.

“Things like aspirin, or wart remedies or if you’ve ever been to the dentist and had an injection to numb your mouth, that’s thanks to a plant,” she says. “If you’ve ever had to deal with cancer, many of our core cancer therapeutics come from plants.”

But there’s a whole lot of plants out there. So how do you figure out which to take back to a lab, to see if it can help fight drug-resistant bacteria? One way is to study traditional knowledge to find out how plants are or were used by native and indigenous people.

In the paper published in the journal Scientific Reports, Quave and other researchers looked to a different kind of source: A Civil War-era book by a Confederate botanist.

Learning From The Civil War

“During the Civil War, there was a blockade of the Confederacy by the Union, and that prevented them from easily importing a lot of different goods, among them contemporary medicines like quinine and chloroform and laudanum,” explains Micah Dettweiler, a researcher in Quave’s lab at Emory and the lead author on the paper.

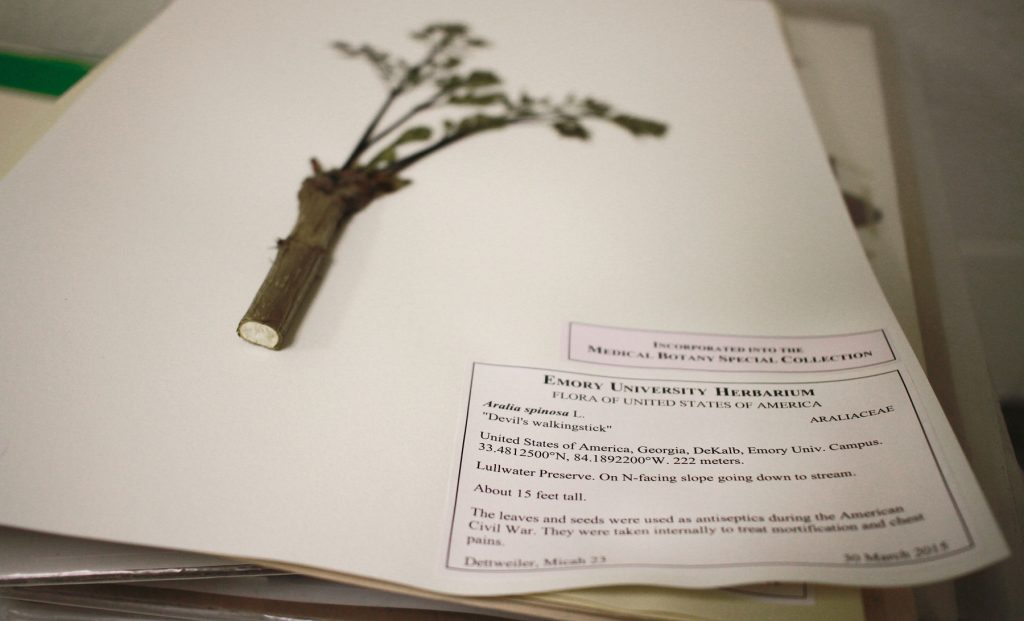

The Confederacy commissioned a botanist named Francis Porcher to go out and survey medicinal plants in the South to find substitutes for those medicines. Porcher published a book in 1863, “Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests,” on useful and medicinal plants of the Southeast – plants the Confederacy could use.

The Emory researchers set out to confirm some of those recommendations. Scientists from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research also contributed to this work.

Many of the plants, they couldn’t find in Atlanta. But a few are still common. In fact, they were able to collect samples right on the Emory campus. White oak, tulip poplar and a shrub called devil’s walking stick were the focus of the study.

“And what we found was pretty interesting,” says Quave.

They were looking for sort of side doors to addressing bacteria: maybe not outright killing bacteria, but making them less toxic, or helping existing antibiotics work better.

Quave says all three of the plants have compounds that could help fight some types of bacteria. White oak showed promise in keeping bacteria from growing. Devils walking stick hindered bacterial cells from communicating with each other. Tulip poplar worked on communication, and also on preventing bacteria from forming a sticky protective film.

The findings could help in the arms race against bacteria, says Jean Molina, a botanist at Long Island University, who was not involved in the study.

“If we’re going to make new antibiotics, they have to target different parts of the bacteria so that it’s harder for the bacteria to evolve resistance,” she says. “It’s actually great research.”

Previous Knowledge

Porcher, the Confederate botanist, wasn’t the one who discovered the uses of these plants.

“He’s drawing on the knowledge of the native peoples. Also drawing on knowledge of European settlers who were looking for similar plants in the U.S. And then finally, in some cases, drawing on knowledge from African Americans.”

So the Confederate Army was likely looking to learn from people it was fighting to keep enslaved, and also from people who’d been forced to leave.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation had been removed from the Southeast a few decades before Porcher’s book was published. But RaeLynn Butler, manager of the historic and cultural preservation department at the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, says the plants they used — and knowledge of how they used them — would have still been around.

“So we’re about 30 years away from when he wrote this book, but I don’t think that much changed,” she says.

Butler says she’d like to be contacted for this kind of research, since the tribe might have been able to provide information, too, say, in how they prepare white oak for medicinal use.

Still, she and Turner Hunt, an archaeological technician for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation who has a background in paleoethnobotany, say the findings in the study are reaffirming.

“It’s good that they’re out there looking at these things. And our ancestors in the past probably knew something very similar along these lines and knew how to treat people,” Hunt says.

Quave says that’s the most valuable part of this paper to her, not just confirming the Civil War survey, but validating the knowledge that was behind that survey.

“This is something that native peoples of the Southeast used for centuries if not millennia, and now we’ve uncovered how it works against these different pathogens,” she says.

The next step is to figure out which molecules in the plants worked against the bacteria, then test those.