'I'll still teach the same way,' Atlanta teacher says despite new 'divisive concepts' law

It’s now illegal in Georgia to teach certain “divisive concepts” in K-12 public schools. That includes teaching that the U.S. is systemically racist or that individuals are inherently racist. Critics say the law is an attempt to stop teachers from mentioning race at all in the classroom.

But Corinthia Howard Knight, a teacher at Atlanta’s Frederick Douglass High School, isn’t shying away from conversations about race.

Pop Quiz

On a Wednesday in May, students in Knight’s American Government class are taking a test. They didn’t know ahead of time and it’s not the kind of test they’re used to taking. It’s a literacy test like Black people used to have to take in the South during the Jim Crow era to vote.

“Now remember, if you get one question wrong, that means that you cannot vote,” Howard Knight reminds her class of the rules that existed at the time. “All right, everybody got it?”

They have ten minutes to answer 30 questions. All of Howard Knight’s ninth-graders are students of color.

She lets them talk and work together during the test but sticks to the ten-minute limit. The students mumble about the questions, one of which asks them to spell the word “backwards” forwards.

“How are you supposed to do this when it don’t make sense in the first place?” one student asks.

When time’s up, Howard Knight goes over the answers. There’s a general consensus that the questions are silly — ranging from things like, “Cross out the shortest word in this sentence,” to “Draw a line through the last word in this line.”

Howard Knight explains that even though the questions on the test may seem ridiculous now, they were a real impediment used to keep African Americans from voting.

“You had people during this time period who actually wanted to vote, but they couldn’t because this was one barrier that gave us,” she says. “So this goes back to this is why it’s important to talk about race in the classroom.”

Historical Accuracy

Lawmakers who drafted the divisive concepts bill say it shouldn’t interfere with teaching history, as Howard Knight is doing. But some teachers have wondered how they can accurately teach history without teaching about systemic racism.

Fellow Douglass social studies teacher Anthony Downer says it’s impossible.

“How are you going to teach three-fifths compromise if you cannot teach white supremacy and that the United States is racist?” Downer said during a recent press conference after Kemp signed the education bills. “How can you not teach intersectionality when you have to teach about the lived experiences of people throughout history, with different identities and different experiences?”

Some critics of the new law have said it could have a “chill effect,” meaning teachers will shy away from ANY conversations about race because they don’t want to be penalized. Howard Knight isn’t worried.

“I’ll still teach the same way because as a teacher…I don’t give my personal opinion, I just give the facts and make sure that they have an accurate depiction of what history is all about,” she says.

Making It Relevant

Because this is an American Government class, Howard Knight has been teaching her students about several of the bills the legislature passed this year, including divisive concepts. On this particular day, she shows her class a bunch of slides, starting with one where Gov. Brian Kemp is signing a stack of education bills.

“So as you can see, the people who are surrounding him don’t look like us or anything along that line,” she says. “These are probably his constituents.”

Most of the people surrounding Kemp in the photo are white.

“Think about some of the things that are dividing us in America at this time,” she says. “Can anybody think about some things at this point that’s dividing us?”

“Well, race,” one student says.

“All right, very good, race,” Howard Knight says. “That’s basically what this law is all about: how can I as a school teacher sit here and actually talk about race in the classroom without offending others?”

“I’ll still teach the same way. I don’t give my personal opinion. I just give the facts and make sure that they have an accurate depiction of what history is all about.”

Corinthia Howard Knight, teacher at Atlanta’s Frederick Douglass High School

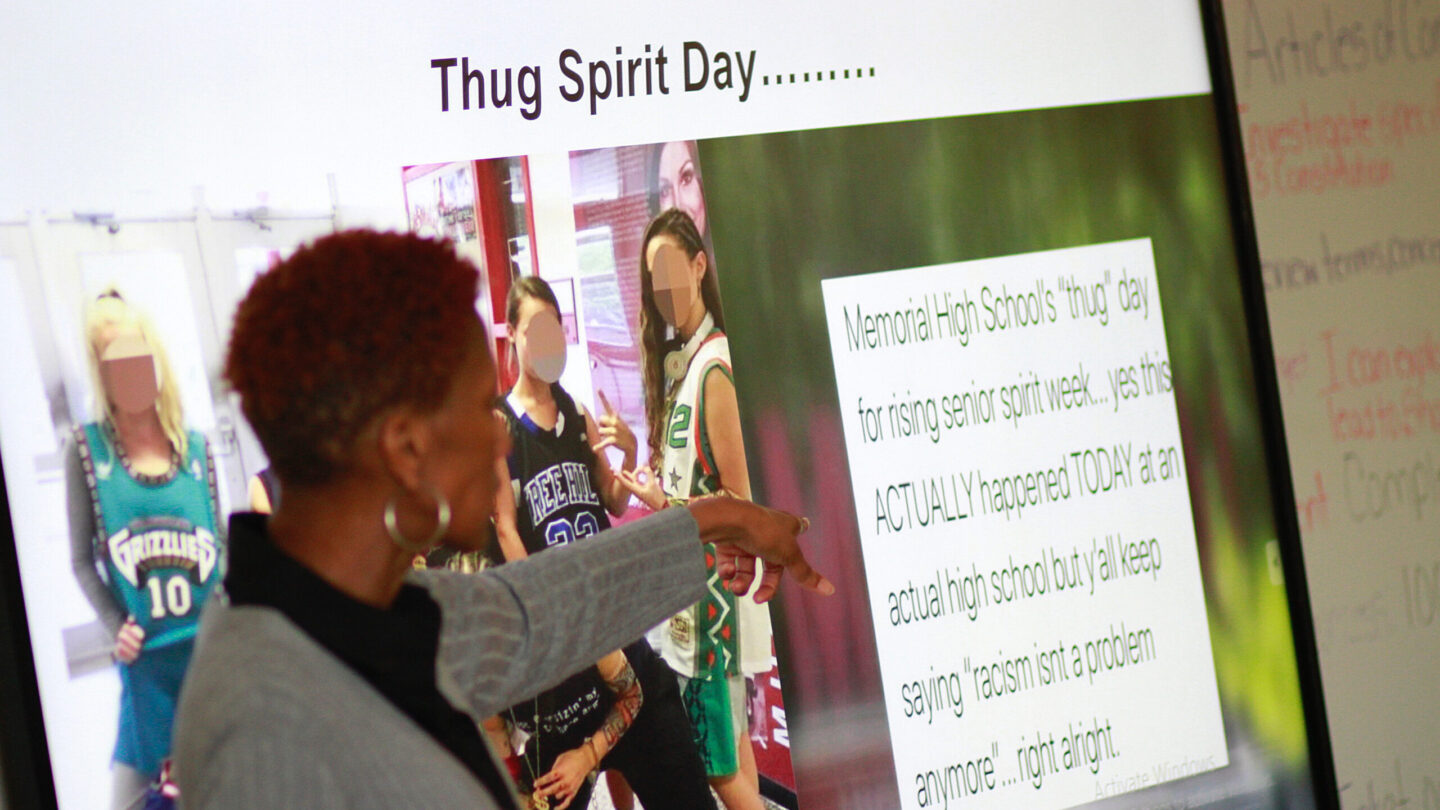

Howard Knight then moves through a series of slides of racist incidents that have caught media attention.

The only Black student on a white basketball team in Laguna Hills, California endured racial slurs shouted at him by the opposing team during a game.

Howard Knight’s students discuss why the white students acted this way. A student named Keyon says they learned from their parents.

“Children are constantly watching adults because they have no one else to guide them,” he says. “They can’t guide themselves in the world and when they see an adult calling a black person a monkey, they’ll do the same thing once they get older.”

But another classmate has a different take.

“I agree and disagree,” he says. “Yeah, you learn some things from your parents but you learn more things on the internet because nowadays they putting everything on the internet.”

Howard Knight goes through several more examples: a teacher who made Black students pick cotton as part of a lesson on slavery; a racist promposal; and white celebrities in blackface.

Howard Knight tells her students they need to talk about race so incidents like this don’t keep happening.

“If we don’t talk about race in the classroom, we’re going to continue to get this,” she says, pointing to the slides of celebrities in blackface. “Remember, these are current, this is nothing that took place two years ago, five years ago, this took place maybe like a month or two ago.”

Howard Knight wants them to connect what’s happening at the state Capitol to their own lives. So, in the coming years, she plans to show them how government works up close.

“They will have to participate in PTAs, they’ll have to go to a city council meeting,” she says. “We’re planning [for them to] go to the state Capitol so they can become more engaged and understand who the people represent them, and how they can see, hear and have their voices heard through their representatives.”

They’re likely to run into fellow students there. Students were a persistent voice at the Capitol this year, testifying about education bills and in some cases shaping them. That’s something Howard Knight wants for her students: to find their voices and use them.

A note of disclosure: The Atlanta Board of Education holds WABE’s broadcast license.