Ga. Coalition: Journalists Attacked, Arrested On U.S. Streets As Protests Escalate

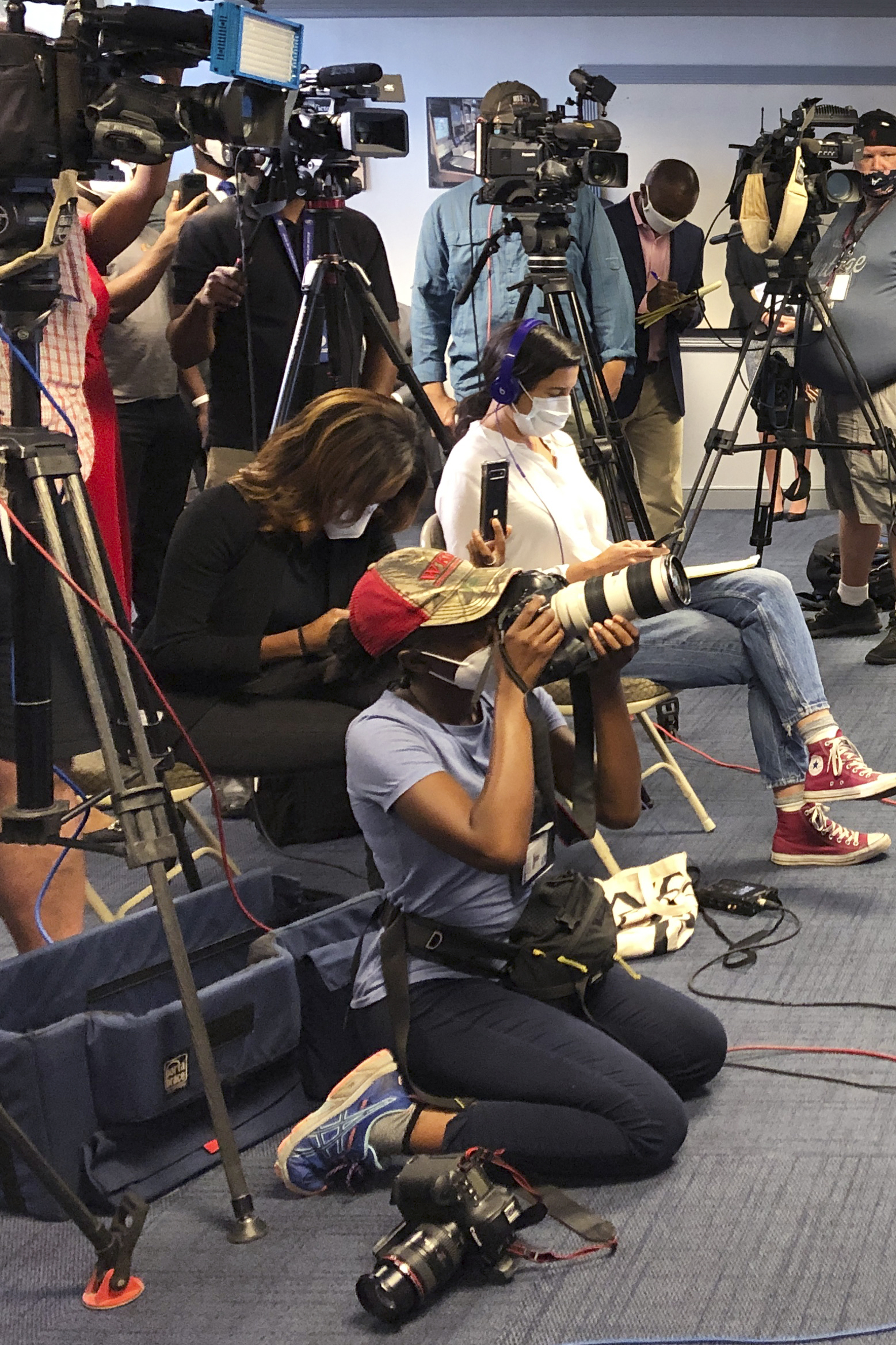

Atlanta Journal-Constitution staff photojournalist Alyssa Pointer works during a news conference Tuesday in Atlanta. Pointer was detained by officers of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources during a protest downtown. Pointer said her press badge was clearly displayed, and she identified herself to law enforcement.

Kate Brumback / Associated Press

A coalition of Georgia journalism organizations is condemning police for detaining reporters covering the George Floyd protests in Atlanta and nationwide.

Locally, one was Atlanta Journal-Constitution staff photographer Alyssa Pointer, who was covering protests Monday when officers from the state Department of Natural Resources detained her.

According to the Georgia chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, Pointer identified herself, and her press badge was clearly displayed. She had her hands zip-tied behind her back and was not released until other reporters intervened.

Another, former Georgia Society of Professional Journalists President Haisten Willis, was freelancing for the Washington Post when he was handcuffed and searched by a group of police in riot gear Sunday night in Atlanta. Willis told WABE that police claimed his digital press credential wasn’t legitimate, and it wasn’t until they found a business card in his back pocket that he was released.

SPJ Georgia President Charlotte Norsworthy sat down with “Morning Edition” host Lisa Rayam to discuss the anxiety the week has caused for journalists on the front lines.

The Atlanta Police Department has apologized for any misunderstandings and said the agency stands by all press freedoms.

However, SPJ Georgia has stood firm that the detainments of Willis and Pointer deprived them of First Amendment rights. Other reporters have suffered permanent damage over the past week.

In Minneapolis, freelance photographer Linda Tirado believes she was shot in the left eye by a rubber bullet fired by police.

“I was aiming my next shot, put my camera down for a second, and then my face exploded,” she told The New York Times.

“I immediately felt blood and was screaming, ‘I’m press! I’m press!’”

Tirado’s Twitter updates show her permanently blind in her left eye, and doctors telling her it is unlikely her sight will return.

Despite rubber bullets’ capability of permanently disabling, injuring and killing civilians, police nationwide have been shooting the bullets into crowds of demonstrators and reporters, regardless of where they land.

BMJ medical journal conducted a systematic review of deaths, injuries and permanent disabilities from rubber and plastic bullets from protests and other contexts from January 1990 until June 2017. The study found that the projectiles caused significant morbidity and mortality over the past 27 years, “much of it from penetrative injuries and head, neck and torso trauma.”

BMJ concluded that the bullets should not be appropriate weapons for use in crowd-control settings, given their potential for misuse and associated health consequences, and that “there is an urgent need to establish international guidelines on the use of crowd-control weapons to prevent unnecessary injuries and deaths.”

“What happened to me was pretty minor, I was let go and everything was OK, but I’ve seen reports of much worse happening to journalists,” Washington Post freelancer Willis said.

He discussed interviewing another journalist who was pepper sprayed by law enforcement, despite holding up press passes and identifying himself.

“Protesters, or at least people with protesters, have also attacked journalists,” Willis said.

“It’s a scary time to be out there.”