This coverage is made possible through a partnership with WABE and Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future.

A bee buzzed close to Reverend Antwon Nixon, inspecting him as he sat on a bench on a boardwalk on a recent Saturday morning. Stretching out in every direction around him was the Okefenokee Swamp — marshy grass punctuated by patches of still, dark water and by trees reaching up toward the blue sky.

Watching bees and dragonflies dance through the air, seeing a bird overhead, spotting a turtle or an alligator in the water — for Nixon, it all gets at the essence of this place.

“There’s a biblical scripture that says, ‘Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom.’ So coming out here, this feels like this spirituality is a sense of freedom,” Nixon said. “As I see, as free that they are, I get a sense of how free I am.”

Nixon lives in Folkston, on the east side of the swamp, and visits as often as he can.

He’s also involved in the fight against a proposed mine nearby.

As that battle has unfolded over the last four years, a truth has emerged. The swamp elicits powerful feelings. For thousands of years, people have found solace and sustenance in the Okefenokee. Love for the swamp comes up over and over again — from people on both sides of the mining issue. The locals who support the project in hopes that it will bring jobs to their communities share similar childhood memories and generational ties to the swamp as their neighbors who oppose the mine.

“I care deeply about the Okefenokee Swamp and my community,” said Charlton County Commissioner and mine supporter Drew Jones in a legislative hearing last month.

His family has lived in the area for generations, and he said he enjoys spending time in the swamp.

“I care about it as much or more than any of you,” he told lawmakers. “I just feel like both can coexist.”

The mining company, Twin Pines, says its work won’t hurt the Okefenokee. A legion of advocates and scientists disagree. And others say that even if the risk of damage is small, the Okefenokee is too precious to take any chances.

A deeper connection

When Nixon was a kid growing up in Folkston, the Okefenokee was a fun school field trip destination. He remembers being charmed by a huge alligator known as Oscar who had his own island and “ran the place.”

As an adult and the pastor of Mt. Carmel Baptist Church in Folkston, Nixon comes to the swamp for tranquility. He likens it to Eden — a place set aside that needs to be sought out.

“There’s a reason that it’s nestled,” Nixon said. “I think that’s what’s great about it. You have to actually go and find it.”

He’s also learned more about the Okefenokee’s place in history. Older members of the Black community have told Nixon that during segregation, it was a place they could gather and spend time when other outdoor spaces like the beach were off-limits.

“That’s a real deep connection, that when I heard that story, and me being a person of color, you know, it deepened my connection,” he said. “It also strengthened my fight.”

The human history of the Okefenokee goes back thousands of years.

The name itself is a shortened version of a Muskogean phrase for “water shaking.” It’s a reference to the trembling surface of the water caused by navigating the swamp in canoes propelled by poles.

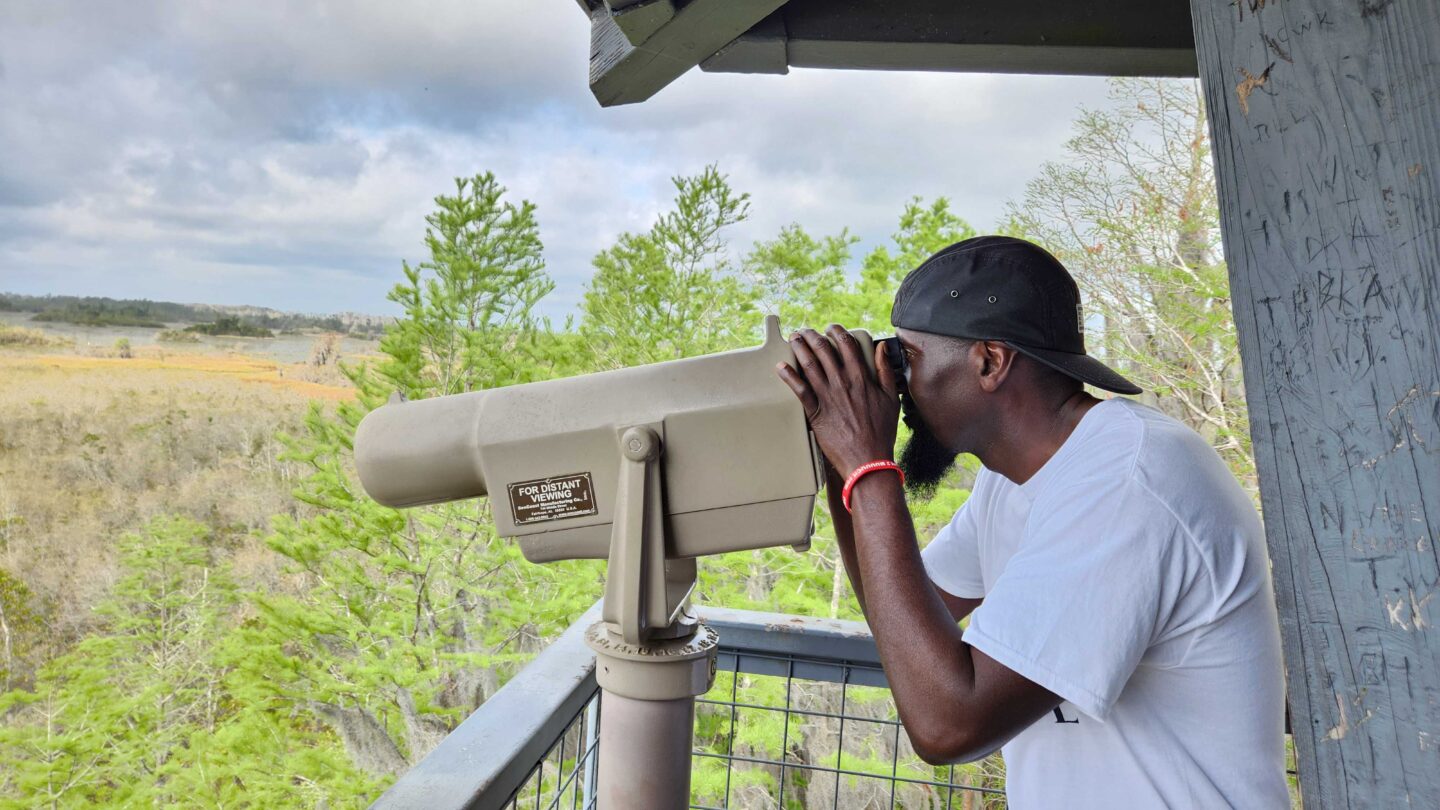

(Molly Samuel/WABE)

“It’s very much part of us as a Muskogean people that I don’t think a lot of current Muskogean people get ever to see,” said Turner Hunt, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Muscogee (Creek) Nation.

The U.S. government forcibly removed the Muskogean people in the 1830s to what’s now Oklahoma. Now, few have the means or opportunity to travel to Southeast Georgia and visit the swamp, Hunt said.

He himself has only recently made the trip for the first time. Yet he felt he recognized it. He said it even smelled familiar — the plants and animals important to the Muskogean religion are still abundant in the Okefenokee.

Hunt sees the swamp and other ancestral sites in Georgia as a direct link back to the thousands of years of Muskogean history before the violence and pain of removal.

“I may have had a different impression of my past, my history, and myself, based off of this idea of the government hates us, kicked us out, set us here in Oklahoma,” he said. “But I can look back, and I can go and I can see these places. And they’re great, amazing places where our ancestors developed all kinds of things. I come from a society that prior to European contact was one of the most complex, socially diverse, ethnically diverse social organisms on North America.”

Understanding that history has helped inspire him to protect ancestral sites like the Okefenokee.

The Muscogee (Creek) Nation is calling for a more thorough environmental review of the mining proposal because “the mining project poses a risk to the cultural and natural resources in the area because the impacts of the mine are not well understood,” according to an emailed statement.

Through working to protect the swamp, Hunt said he’s met current locals who have their own history and ties to the swamp.

“The reason why it’s important to us ended up being some of the same reasons that it was important to other folks,” he said.

For Roy Abbott, visiting the Okefenokee was a lifelong dream. He was captivated by a black and white film he saw about it on TV decades ago. He finally made the trip as an adult after his parents moved to Florida.

“It was like, man, I really made it to the Okefenokee,” he recalled. “It was like a childhood thing that I managed to do as I got older. It’s just a wonder. It’s really a wonder.”

Abbott kept returning more and more until he and his wife moved to the town of Fargo, on the west side of the swamp. He’s now the mayor of Fargo. He said he and his wife still love to take their boat into the swamp and soak up the surroundings.

“My theory is the Okefenokee was put here by someone higher than us. It’s there for us to enjoy,” Abbott said.

“It’s a mirror land,” said Macon astronomer Philip Groce, who enjoys canoeing in the Okefenokee.

The night sky above the Okefenokee is particularly entrancing, Groce said.

The swamp is one of the rare spots where it’s still dark enough to see the Milky Way undimmed by light pollution. As an astronomer, Groce has visited other such places — usually barren landscapes, like the freezing top of a mountain.

“I’ve seen some skies, but it was completely dead,” he said. “The Okefenokee is organic. Very seldom do you see a relationship, a human relationship to the sky, but also, you share it with the animals that also live in that swamp. And you’re always aware of it.”

Earlier this year, Groce led a workshop in the Okefenokee for a group of students from The New School in Atlanta.

“I have never actually been outside of a city and looked up before,” said Zain Khemani, a high school junior at the school. “And let me tell you, the first time I actually saw the sky, I was like, ‘wow.’”

Khemani was so moved by the trip that it inspired him to speak out against the proposed mine.

The mining project needs approval from the Environmental Protection Division of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to proceed, and earlier this year the agency collected public comment on the land use plan for the mine. Khemani joined the virtual meeting so he could speak up — something he said he likely wouldn’t have done if he hadn’t visited.

Prior to the Okefenokee field trip, Khemani said he never spent much time outdoors, joking he “was not made to touch grass.”

The Okefenokee changed that, he said.

“When we went down there for one of the first times in my life I genuinely, like – I got it.”