Westside Atlanta lead pollution gets cleanup, new job opportunities

Cleanup of lead pollution in Westside Atlanta neighborhoods is continuing through the winter, but earlier this fall, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and its partners celebrated two significant milestones. At back-to-back events in English Avenue, the federal agency gathered neighbors to celebrate millions of dollars in investments for the cleanup and a job training initiative for local residents.

In front of her freshly manicured lawn, Myrtle Dansby held some mail in her hand as she looked over her screened-in front porch and little yard filled with planter boxes with pink flowers. The house has been in her family for a long time. It’s where she raised her six kids, each of whom she put through college. It was virtually impossible to tell the EPA had just dug up the top two feet of dirt to dig out lead.

“I didn’t know until [about the lead] really they came over and was talking to me about it,” Dansby said. She is one of the homeowners who has already had her property cleaned up and said she was happy to let them do so after learning about the harmful effects of lead.

English Avenue and Vine City, two neighborhoods in West Atlanta, have a bit over 2,000 properties contaminated with lead pollution. Since Emory researchers tested for lead in the area in 2018 and found hazardous levels of contamination, the EPA conducted a lengthy study and named the area a Superfund Site, a federal designation for polluted areas that need cleaning.

“We know that there are 2000 homes, or residences, and other properties in this area that potentially have lead that is above our risk levels that causes us to be concerned,” said Jeaneanne Gettle, EPA acting regional administrator for the Southeast. “We’ve been able to sample about 1000 of those, and so one of our asks is that residents in this area to look at our site map and see if you’re in that.”

EPA remedial project manager Alayna Famble said many neighbors have had their grandchildren playing in yards. She said they care about the well-being of their community and have been engaging with the cleanup. But there’s still work to be done to reach out to other homeowners for them to grant the EPA access to test for and remediate the lead.

With an extra $30 million from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, Famble said her team has doubled their efforts and started remediating properties faster and doing more outreach.

On top of that, Famble said there are complicating factors: there is a high rate of renters in the area, so while the renters are willing to have soil tests done and are interested in cleaning up the lead, their landlords might not be. Many properties change hands frequently, making the owners hard to track down. There are absentee landlords and large international holding companies that haven’t responded to the EPA, leaving potential lead pollution inaccessible to be removed.

Lead is a health hazard, particularly to young children. Even at low levels, it can cause developmental and learning delays, behavior problems and slow growth. In adults, it can cause reproductive issues in men and women, high blood pressure and hypertension, nerve disorders and more.

Improving community health and prosperity

Beyond cleaning up lead pollution, the EPA invested in the Westside Lead Superfund Site to provide job training for Vine City and English Avenue residents. The Superfund Job Training Initiative, or SuperJTI, is specifically for communities burdened by legacy contamination. In Atlanta, that’s the Westside Superfund Site, an area of roughly 2,000 properties — many homes — where unsafe levels of lead contaminate the ground.

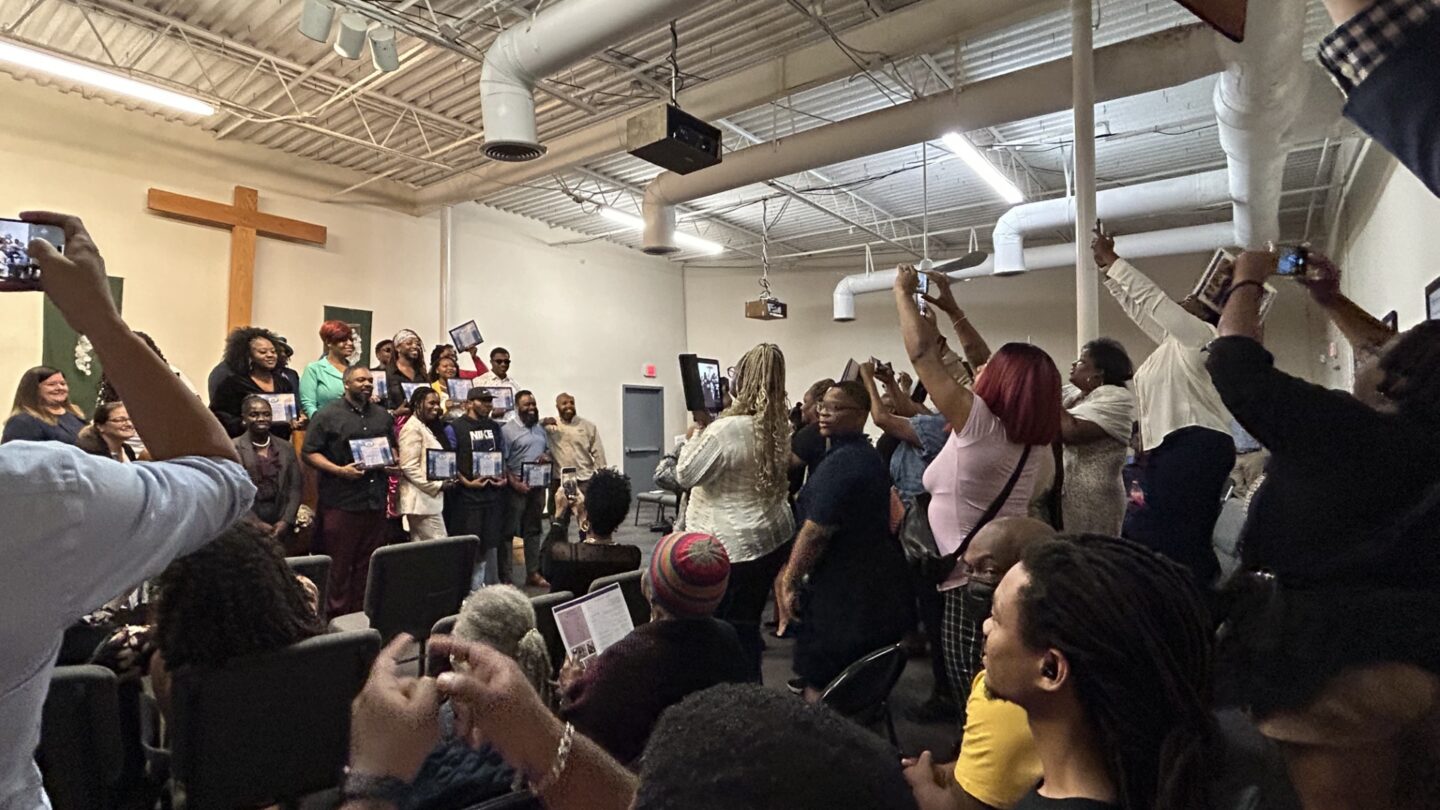

The 20 graduates from Westside Lead gathered at a church in English Avenue to celebrate completing the program. Dressed to the nines, the church auditorium was packed with friends and family to celebrate the accomplishment. Each graduate left the program with a slew of specialized certifications like lead paint removal certifications and the hefty 40-hour “HAZWOPER” — the OSHA Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response certification.

The program in Atlanta is one of 23 completed in the country so far. It’s part of the EPA’s overall Environmental Justice initiatives, aiming to holistically approach pollution that has disproportionately impacted communities of color.

Just last year, the agency announced its new Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights office aimed specifically at matching grant funds to where they’re needed most, developing local partnerships and ensuring compliance and enforcement of civil rights laws pertaining to the environment.

From the podium on stage at graduation, program participant Dante Hill said the training didn’t just provide certifications. It’s opening the door for upward mobility in a career beyond day laborer jobs.

“It’s a blessing to know that I can exceed that and I can take my credentials and everything that I learned and really help my community for real, for real, like I wanna help my community for real,” Hill said.

Graduate Javantae Moore said the program emphasized the program participants’ ability to give back to their communities through this line of work.

“It’s all about community involvement, community initiative,” Moore said. “We can really kind of take charge with these certifications and lead the way on different hazardous environmental cleanup situations.”

Her background is in environmental sustainability, and her degree focused on analysis, using computers and site inspections. The SuperJTI, she said, was a great opportunity to expand her knowledge within the environmental industry, connect with peers and set her sights on new job opportunities, including other Superfund sites.

“And they’re all over the country,” she said. “So this is experience and education that we can take and not only you know, in Atlanta and Georgia, but elsewhere throughout the country too.”

For now, they could work in their own community on the Westside lead clean up or get hired by a company like Skeo Solutions, which partnered to teach the program. Or, they could go further and manage superfund site clean-ups around the country. Some of the graduates missed the ceremony entirely because they were already at their new jobs.